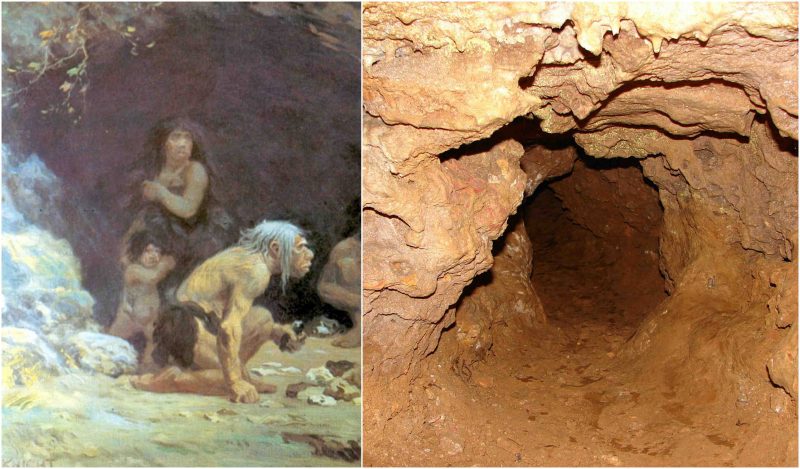

Neanderthals have long be believed to be thuggish cavemen that barely scraped an existence on the barren plains of Ice Age Europe. This depiction is so ingrained that we use the word Neanderthal to insult someone who might not be as intelligent.

This image might be about to get an extreme makeover, however. Recent discoveries suggest that Neanderthals had a complex society and were skilled toolmakers with adept hand-eye coordination.

One of these discoveries was made in a cave located in southwest France. Back in 1992, researchers found ring-like structures about 1100 feet (336 meters) from the cave’s entrance. These structures were made out of about 400 stalagmites that were taken from the cave. A team of researchers at the University of Bordeaux have dated these structures, by examining the stalagmites, as being approximately 176,000 years old. This is within the long glacial period, and they could have used as a temporary refuge from the cold.

The dating is particularly significant because it was previously thought that stone buildings had only emerged in modern human society and alongside the development of farming around 10,000 years ago. As this new study, which has been published in the journal Nature, suggests, Neanderthals were already constructing stone structures long before that 10,000-year mark. It wasn’t until recently that research and excavation on the Bruniquel cave has begun.

The structures outside of the cave form several rings, one of which was nearly twenty-two feet wide. In total, the rings measured 367 feet (112 meters) in length. Experts suggest that these structures, apart from serving as a refuge, could have had symbolic meaning to the Neanderthals who built them.

The lead author of the study, Professor Jacques Jaubert, told MailOnline that the Neanderthals must have moved around 2.5 tons of material. This would have required a remarkable amount of cooperation as the group worked together with a preconceived plan with leaders, advisers, and manufacturers. “All this indicates a structured society,” he said. “—having a project, then to find the raw material, then tear [the] stalagmites. Then fragmenting, knapping [them] into regular elements.”

The inside of the cave has also yielded discoveries. Archaeologists have found marks inside the cave that were made by fire. This not only adds to the theory that Neanderthal society was cooperative, but that they also had mastered the ability of working underground with artificial light.

“We did not expect a Neanderthal attendance in the deep underground cave, so far from the entrance,” Professor Jaubert confessed.

These marks were found deep inside the cave. Previous signs of human habitation in the dark zones of caves only reach 98 to 130 feet (30 to 40 meters) deep. The Bruniquel occupation, explained Professor Chris Stringer, is around ten times deeper and shows constructions that are as complex as those made by modern humans only 20,000 to 30,000 years ago.

Professor Stringer, an anthropologist at the National History Museum, said that these findings “would be significant for any period of time, but at around 175,000 years, these must have been made by early Neanderthals, the only known human inhabitants of Europe at this time.”

Neanderthals initially emerged around 280,000 years ago. They inhabited much of Europe and parts of Asia, eventually dying out about 40,000 years ago. Their demise coincided with the entrance of anatomically modern humans on to the scene. It was often thought that Neanderthals died out because they were inferior to and unable to compete against the more sophisticated Homo Sapiens. Now, however, experts have admitted that the evidence they have found suggests that Neanderthals had fully human capabilities.

The Bruniquel cave was not the first indication of this. A 60,000-year-old multi-purpose bone tool unearthed in France suggests that Neanderthals understood how to use bones to make useful devices. Neanderthals might have used powdered rocks to lower the temperatures needed to light wooden shavings. If they did control fire in this way, there are wide-ranging implications regarding their cognitive abilities, society, and culture.

A building, measuring twenty-six feet wide, has been discovered by researchers hailing from the Muséum National d’Histories Naturelle in Paris. It was built around 44,000 years ago from mammoth bones, and it suggests that Neanderthals may have built homes using the materials they found around them. Many of the bones had been decorated with carvings and ochre pigments. Inside Gorham’s Cave in Gibraltar are cross-hatch engravings—these are thought to be the first known examples of Neanderthal rock art. Possible Neanderthal jewelry might have been found as well. Eight talons that were found at a 130,000-year-old Neanderthal site in Krapina, Croatia, might have been worn as a necklace.

Dr. Simon Underdown, a senior lecturer in Biological Anthropology from Oxford Brooks University, weighed in on the subject. “If the dates are correct then this is a hugely exciting development in our understanding of the lives of the Neanderthals.” He said. “The considerable time and effort needed to build such a structure clearly indicate a shared plan and extensive cooperation. It’s finally time to put away the old image of the Neanderthals as stupid and embrace them as a fully human species.”

As for the structures at the Buniquel cave, they remain a mystery. “The purpose of the structures and concentrated combustion zones which are mostly on the broken stalagmites rather than on the ground remain enigmatic, but they demonstrate that some Neanderthals, at least, were as much at home deep within the cave as at its entrance.” Professor Stringer noted.

Researchers at the site hope to continue excavation. Ideally, they would find the remains of the humans that may have constructed the structures. “The project this year [is] to make a test-pit inside the great structure, to survey the archaeological soil and, if it’s possible, to find some remains.” Professor Jaubert said. If there were remains, human or otherwise, it would help determine whether the structures were a functional refuge or shelter. They could have had wood or skin roofing. If the structures were had symbolic or ritual significance, evidence proving so would hopefully be found as well.

These structures and artifacts are not the only things that Neanderthals have left for us. Humans and Neanderthals are thought to have coexisted for thousands of years and even interbred. In fact, Europeans have roughly two percent Neanderthal DNA. DNA analysis has shown that humans and Neanderthals both carried the genes that enable us to speak.

Some of the Neanderthal genetic legacy is beneficial; our improved immunity to diseases may have stemmed from Neanderthals. Scientists have found that part of our HLA system, the system that helps white blood cells to identify and destroy foreign material in the body, could have come from Neanderthals.

Humans also seemed to have inherited the negative too. Researchers from Oxford and Plymouth Universities have found that genes thought to be risk factors in cancer were present in the Neanderthal genome. The same has been suggested, although not definitively found, for diabetes. Other studies suggest that humans outside of Africa (i.e. the humans who interbred with Neanderthals) are more vulnerable to Type 2 Diabetes. A gene that can cause diabetes in Latin Americans is also thought to have come from Neanderthals, long before their ancestors colonized the New World. Yet another genetic study from scientists at the University at Buffalo has suggested that Neanderthals may have suffered from psoriasis and Crohn’s disease, a condition that affects the digestive system.

Tracing the evolution of modern humans is a fascinating, and often baffling, task. The modern human ancestor is called Australopithecus Afarensis. Although this ancestor and modern humans appear similar, there are distinct differences. Modern humans have shorter arms and smaller feet—these, experts suggest, shaped human society and behavior.

One of the most baffling physical characteristics of modern humans is the chin. No other species, including our ancestors and our primate cousins, have chins. There have been many different explanations have been put forward for the purpose of this appendage. It perhaps developed as a way to attract mates. Other suggest that our chins are an example of genetic drift and have no evolutionary purpose whatsoever.

Recent research suggests that the jaw evolved to deal with the fact that cooking was making food softer. As detailed in a paper, researchers from the University of Florida calculated the chin began to emerge between six million and 200,000 years ago, with the most likely estimate being two million years ago. This timing coincides with the enormous leap forward in human intelligence, about the same time of the invention of cooking.

Another study published, however, suggests a different reason for the chin: it was the result of falling hormone levels that also caused our ancestors to become more sociable and stopped them fighting over territories.