The Fontanelle cemetery in Naples is a charnel house, an ossuary, located in a cave in the tuffa hillside in the Materdei section of the city.

It is associated with a chapter in the folklore of the city. By the time the Spanish moved into the city in the early 16th century, there was already concern over where to locate cemeteries, and moves had been taken to locate graves outside of the city walls. Many Neapolitans, however, insisted on being interred in their local churches.

To make space in the churches for the newly interred, undertakers started removing earlier remains outside the city to the cave, the future Fontanelle cemetery. The remains were interred shallowly and then joined in 1656 by thousands of anonymous corpses, victims of the great plague of that year.

Sometime in the late 17th century—according to Andrea De Jorio, a Neapolitan scholar from the 19th century, great floods washed the remains out and into the streets, presenting a grisly spectacle. The anonymous remains were returned to the cave, at which point the cave became the unofficial final resting place for the indigent of the city in the succeeding years—a vast paupers’ cemetery.

It was codified officially as such in the early 19th century under the French rule of Naples. The last great “deposit” of the indigent dead seems to have been in the wake of the cholera epidemic of 1837.

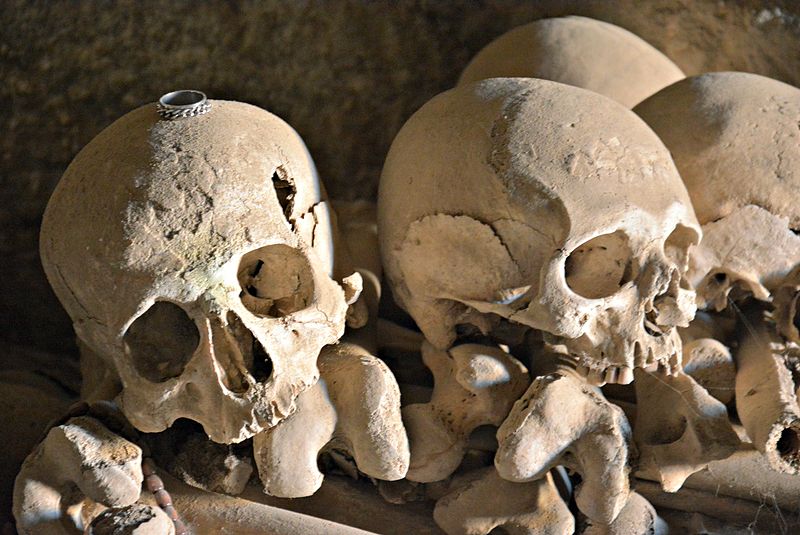

Then, in 1872, Father Gaetano Barbati had the chaotically buried skeletal remains disinterred and catalogued. They remained on the surface, stored in makeshift crypts, in boxes and on wooden racks.

A spontaneous cult of devotion to the remains of these unnamed dead developed in Naples. Defenders of the cult pointed out that they were paying respect to those who had had none in life, who had been too poor even to have a proper burial. Devotees paid visits to the skulls, cleaned them—”adopted” them, in a way, even giving the skulls back their “living” names (revealed to their caretakers in dreams).

An entire cult sprang up, devoted to caring for the skulls, talking to them, asking for favors, bringing them flowers, etc. The cult of devotion to the skulls of the Fontanelle cemetery lasted into the mid-20th century. A small church, Maria Santissima del Carmine, was built at the entrance.

In 1969, Cardinal Ursi of Naples decided that such devotion had degenerated into fetishism and ordered the cemetery to be closed. It has recently undergone restoration as a historical site and may be visited.