Surprisingly there are much more than just 5. And there isn’t any information if they got to Wolverine yet, but still, their projects vary from bizarre to genius, and from to monstrous to funny. Read about 5 of these interesting experiments by the U.S. military.

The U.S. Camel Corps

In the 1830s America’s westward expansion was being severely curtailed by the inhospitable terrain and climate faced by pioneers and settlers. This was particularly the case in the southwest, where arid deserts, mountain peaks, and impassable rivers were proving to be an almost insurmountable obstacle to men and animals alike. In 1836, U.S. Army LT George H. Crosman hit upon an unusual idea to deal with the situation. From his experiences in the Indian wars in Florida, he was convinced that camels would be useful as beasts of burden, and encouraged the War Department to use camels for transportation.

The animals were perfect for making the long, grueling treks then being mapped out across the country. Still, not much came of the idea until about 15 years later when, thanks to some publicists like the well-known diplomat and writer George Perkins Marsh, the “Camel Transportation Company” was formed to operate a camel express between Texas and California and down to Panama, later to be called the “Dromedary Line.” It wasn’t alone: there was also an American Camel Company.

But while the camels’ hardiness was never in doubt, the Civil War effectively ended their stint in the armed services. Army brass lost interest in the outfit during the march to war, and it was finally disbanded after the Confederacy — ironically, with Davis as its president — captured its base at Camp Verde, Texas. Most of the remaining camels were later auctioned off to circuses and private citizens. Others were turned loose, and their descendants were still being sighted in the wild as recently as the 1940s.

Project Iceworm

In 1958, the U.S. Army launched one of the most audacious experiments of the Cold War. As part of a top-secret project dubbed “Iceworm,” they drew up plans to hide hundreds of ballistic missiles under Greenland’s ice caps. Once operational and concealed beneath the Arctic snows, the sites would be poised for potential nuclear strikes on the Soviet mainland.

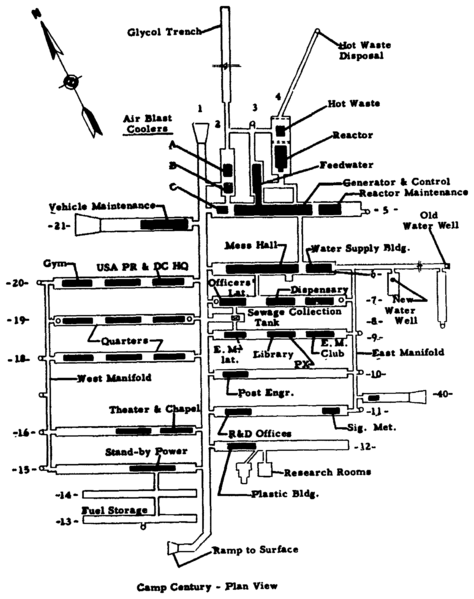

Camp Century—aka “Project Iceworm”—was a “city under ice,” according to the U.S. Army, a nuclear-powered research center built by the Army Corps of Engineers under the icy surface of Greenland. The 200-man base was massive , described by some as an underground city, and consisted of 21 steel-arch covered trenches. With a total length of 3,000 meters, these tunnels also contained a hospital, a shop, a theater and a church. The base was powered by a portable PM-2A nuclear reactor that produced two megawatts of power for the facility.

The idea that the moving terrain of a glacial ice sheet could be considered a stable-enough launching point for nuclear missiles is astonishing, and the idea that the U.S. Army once ran a top secret, and rather Metallica-sounding, “city under ice” just shy of the North Pole only adds to the story’s disarming surrealism.

Camp Century may have been a technological marvel, but it was no match for Mother Nature. After only a few years, shifts in the ice caps caused many of its tunnels to become warped and structurally unsound. Convinced Greenland was no place for nuclear weapons, the Army reluctantly scrapped the project in 1966.

Project Pigeon

It’s 1943, and America desperately needs a way to reliably bomb targets in Nazi Germany. What do we do? For B.F. Skinner, noted psychologist and inventor, the answer was obvious: pigeons.

The famed behaviorist got the idea for his “Bird’s-Eye Bomb” while watching a flock of pigeons in flight. “Suddenly I saw them as ‘devices’ with excellent vision and extraordinary maneuverability,” he wrote. “Could they not guide a missile?” Skinner approached the National Research Defense Committee with his plan, code-named “Project Pigeon.” Members of the committee were doubtful but granted Skinner $25,000 to get started.

The intent was to train pigeons to act as “pilots” for the device, using their cognitive abilities to recognize the target. The guidance system consisted of three lenses mounted in the nose of the vehicle, which projected an image of the target on a screen mounted in a small compartment inside the nose cone. This screen was mounted on pivots and fitted with sensors that measured any angular movement.

However, Skinner’s plans to use pigeons in Pelican missiles were considered too eccentric and impractical; although he had some success with the training, he could not get his idea taken seriously. The program was canceled on October 8, 1944, because the military believed that “further prosecution of this project would seriously delay others which in the minds of the Division have more immediate promise of combat application.”

The Edgewood Arsenal Drug Experiments

The Edgewood Arsenal human experiments took place between 1948 and 1975. The aim of the experiments was to analyze the impact of chemical warfare agents on military personnel to test the likes of vaccines, pharmaceuticals, and protective clothing.

For two decades during the Cold War, the United States Army tested chemical weapons on American soldiers at Edgewood Arsenal, a secluded research facility on the Chesapeake Bay. Thousands of men were recruited to volunteer; at the arsenal, they were exposed to chemicals ranging from mustard gas and sarin to LSD and PCP.

Overall, about 7,000 soldiers took part in these experiments that involved exposures to more than 250 different chemicals, according to the Department of Defense (DoD). Some of the volunteers exhibited symptoms at the time of exposure to these agents but long-term follow-up was not planned as part of the DoD studies.

While the tests produced reams of documentation on the effects of the substances, they discovered no wonder drugs and created very little practical intelligence. Many of the subjects, meanwhile, were left with psychological trauma and lingering health problems.

The experiments were abruptly terminated by the Army in late 1975 in an atmosphere of scandal and recrimination as lawmakers accused researchers of questionable ethics. Many official government reports and civilian lawsuits followed in the wake of the controversy.

The FP-45 Liberator

Early 1942 was a time of crisis for the Allies. Against the bleak backdrop, Allied planners were tirelessly exploring ways to stem the Axis aggression and take the fight to the enemy. In March 1942, a Polish military attaché requested that the Allies provide arms to the populations of German-occupied countries. The U.S. Army’s Joint Psychological Warfare Committee was tasked with devising a plan to develop such arms.

The result was the FP-45, a small, single-shot 45 caliber pistol, developed by the Inland Manufacturing Division of General Motors. The theory was that resistance fighters would use the crude pistols to assassinate enemy troops and then take their weapons.

The guns would also have a psychological effect since the thought that every citizen might be armed with a “Liberator” would strike fear into the hearts of occupying soldiers. The U.S. produced 1 million FP-45s between June and August 1942, but the pistols failed to ever catch on in the field.

Allied commanders and intelligence officers found them impractical, and European resistance fighters tended to favor the “Sten”—a British-made submachine gun. While some 100,000 Liberators did find their way to Pacific Theater, there’s no documentation on how widely used or effective they were. The remaining FP-45s have since become something of a collector’s item, and working models occasionally sell for upwards of $2,000.