Rollo: First ruler of Normandy

Ragnar Lothbrook is one of the most famous Vikings in history, but his brother, Rollo, was also a major player in the Viking saga. Rollo (c. 846 – c. 932), in some, later sources identified with Ganger-Hrólf and baptized Robert, was a Viking who became the first ruler of Normandy, a region of France. Rollo came from a noble warrior family of Scandinavian origin. After making himself independent of the Norwegian king Harald Fairhair, he sailed off to Scotland, Ireland, England and Flanders on pirating expeditions and took part in raids along France’s Seine river. Rollo won a reputation as a great leader of Viking raiders in Ireland and Scotland and emerged as the outstanding personality among the Norseman who had secured a permanent foothold on a Frankish soil in the valley of the lower Seine.

Rollo later expanded his control of the region, and around the time he died, in about 928, was succeeded by his son, William Longsword. In 1066, another one of Rollo’s descendants, William, duke of Normandy, led a successful invasion of England. William the Conqueror, as he became known, went on to serve as king of England until 1087. More than a thousand years after Rollo’s death, Allied troops during World War II landed on the beaches of Normandy on June 6, 1944, beginning the liberation of Western Europe from Nazi Germany’s control.

Erik the Red: Founded Greenland’s First Norse Settlement

Eirikr rauði Þorvaldsson (approx. 950-1003 AD) was called Erik the Red because of his red beard and hair and perhaps also because of his fiery temper. It is said that he was a particularly hot-headed fellow who, after being exiled from first Norway and later Iceland, finally settled in Greenland. Leif Erikson, the famous Icelandic explorer, was Erik’s son.

Leaving in about 982 from Snæfellsjökull, one of the westernmost points of Iceland, Erik and a small group of men reached land on the opposite shore of Greenland, a land that had been skirted by the Norwegian Gunnbjörn Ulfsson earlier in the 10th century. The party rounded the southern tip of Greenland and settled on an island at the mouth of Eriksfjord (now known as Tunulliarfik Fjord) near Qaqortoq (formerly Julianehåb). From there they explored the west and north for two years, bestowing place names everywhere (a form of establishing personal control). Erik chose the inner area of Eriksfjord for his manor house, which he called Brattahlid (“Steep Slope”). He named the country Greenland, in the belief that a good name would attract settlers. At its peak, the Greenland colony had an estimated 5,000 residents. Following Erik’s death, Greenland’s Norse communities continued on before being abandoned in the 14th and 15th century.

Exactly why the Norse Greenlanders disappeared is a mystery, although a combination of factors might’ve played a role, including a cooling climate and declining trade opportunities.

Olaf Tryggvason: Brought Christianity to Norway

Olav Tryggvason came from England with many ships and men in the summer of AD 995. He came to claim the throne of Norway and to bring Christianity to the country. He went ashore on the island of Moster on the west coast of Norway. He was accompanied by several English priests and a bishop called Grimkjell. On the island, Olav Tryggvason held the first official mass in Norway. About 35 years later Norway was officially a Christian country.

Olaf was born around 968 and is thought to have been raised in Russia following the death of his father. In 991, Olaf led a Viking invasion of England, which resulted in a victory at the Battle of Maldon. Afterward, the English paid off the Vikings in an effort to prevent future attacks, at least temporarily. This type of payment became known as Danegeld. In 994, Olaf and his ally Svein Forkbeard, king of Denmark, launched another raid on England and netted themselves more Danegeld. The following year, Olaf used his loot to invade Norway and was made king after its ruler, Hakon the Great, was murdered.

As a king, Olaf forced his subjects to convert to Christianity; before that, most Scandinavians were pagans who worshiped a number of gods. Olaf’s actions earned him enemies, among them his onetime ally Svein Forkbeard, who wanted to restore Danish rule in Norway, and Erik of Hladir, son of Hakon. In 1000, Olaf was ambushed by his rivals in a battle at sea; however, instead of surrendering, he supposedly jumped over the side of his ship, never to be seen again.

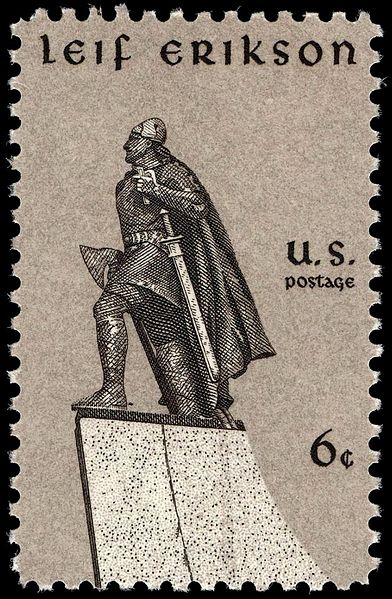

Leif Eriksson: Beat Columbus to the New World by 500 years

Nearly 500 years before the birth of Christopher Columbus, a band of European sailors left their homeland behind in search of a new world. Their high-prowed Viking ship sliced through the cobalt waters of the Atlantic Ocean as winds billowed the boat’s enormous single sail. After traversing unfamiliar waters, the Norsemen aboard the wooden ship spied a new land, dropped anchor and went ashore. Half a millennium before Columbus “discovered” America, those Viking feet may have been the first European ones to ever have touched North American soil.

During his expedition, Leif reached an area he called Helluland (“flat stone-land”), which historians think could be Baffin Island, before traveling south to a place he dubbed Markland (“forestland”), thought to be Labrador. The Vikings then set up camp at a location that possibly was Newfoundland and explored the surrounding region, which Leif named Vinland (“Wineland”) because grapes or berries supposedly were discovered there. After Leif returned to Greenland with valuable timber cargo, other Norsemen decided to journey to Vinland (Leif never went back).

However, the Viking presence in North America was short-lived, possibly due in part to clashes with hostile natives. The only authenticated Norse settlement in North America was discovered in the early 1960s on the northern tip of Newfoundland at a site called L’Anse aux Meadows, artifacts found there date to around 1000.

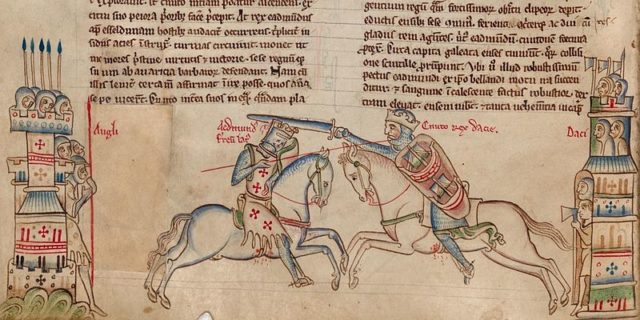

Cnut the Great: England’s Viking King

Cnut the Great (995 – 1035), more commonly known as Canute, was a king of Denmark, England and Norway, together often referred to as the Anglo-Scandinavian or North Sea Empire. After his death, the deaths of his heirs within a decade, and the Norman conquest of England in 1066, his legacy was largely lost to history. The medieval historian Norman Cantor has stated that he was “the most effective king in Anglo-Saxon history”, although Cnut himself was Danish, not British or Anglo-Saxon.

The son of Denmark’s King Svein Forkbeard, Cnut (or Canute) helped his father conquer England in 1013. However, when Svein died the next year, the exiled Anglo-Saxon king, Aethelred the Unready, returned to power. Aethelred passed away in 1016 and was succeeded by his son, Edmund Ironside. Later that year, after Cnut defeated him at the Battle of Ashingdon, Edmund signed a treaty that gave Cnut power over part of England. Just a few weeks later, though, Edmund died and all of England came under Cnut’s rule; his reign there brought stability after years of raids and battles. Denmark, Norway and possibly portions of Sweden also eventually came under Cnut’s control, forming a vast empire. When he died in 1035, his son Harold Harefoot became king of England, serving until his death in 1040. Harthacnut, Cnut’s other son (from his marriage to Aethelred’s widow) then ascended to the throne, but his death in 1042 marked the end of Danish rule in England.

Harald Hardrada: The Last Great Viking Leader

Born Harald Sigurdsson in Norway in 1015, he fought as a teen at the Battle of Stiklestad, waged in 1030 by his half-brother Olaf Haraldsson, the exiled king of Norway, in an attempt to return to power. Instead, Olaf’s forces were defeated, he was killed and Harald went into exile, eventually doing a stint as a mercenary for Jaroslav the Wise, grand prince of Kiev. Harald then traveled to Constantinople and joined the Byzantine emperor’s prestigious Varangian Guard. After becoming a wealthy, accomplished military commander, he returned to Scandinavia by the mid-1040s. There, he formed an alliance with Svein Estrithson, a claimant to the Danish throne, in an effort to combat King Magnus the Good, who ruled Norway and Denmark. However, Harald ditched the partnership with Svein in 1046 when Magnus decided to make him a co-ruler of Norway. After Magnus died the next year, Harald gained full control of the Norwegian throne while Svein became king of Denmark. Harald went on to fight Svein for years, but despite winning the majority of the battles Harald (whose nickname Hardrada translates as hard ruler) opted to make peace with his adversary in 1064 and give up his claims to Denmark.

Harald then shifted his focus to England, invading it two years later with a large force and scoring a victory at the Battle of Fulford Gate. However, just days later England’s new king, Harold Godwinson, wiped out Harald’s army at the Battle of Stamford Bridge, during which Harald — later referred to as the last of the great Viking warrior kings – was killed. Less than a month after that, Norman invaders led by William the Conqueror defeated the English at the Battle of Hastings, during which Harold Godwinson was killed.