It was the 5th of September, 1941, and the Chief of the Imperial Japanese Navy, Osami Nagano, was feeling anxious. He had just witnessed the Emperor raising his voice. For him and the other two attendees of the meeting – Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe and Minister of War Hajime Sugiyama – this was a once in a lifetime experience. The fact was, very few members of Japanese society had ever been given the privilege of hearing the sound of Emperor’s voice, let alone witness an emotional outburst.

This was just one of many traditional traits of the deeply conservative ruling order in Japan. And not the only one Hirohito was to breach in the coming years. The meeting in question was about the Army persuading the Emperor to enter an open war with the West. In Europe, WWII was already raging, and the Third Reich seemed unstoppable. In Asia, the Japanese were bogged down in China in the Second Sino-Japanese War. Hirohito seemed unwilling to enter another battle he could not win.

By the 3rd of November, Army chiefs managed to make their case to the Emperor. Hirohito was onboard and with war preparations underway, Nagano was detailing the plan to attack Pearl Harbor. A month later Japan went all in, confident that the Axis Powers were going to change the world order once and for all – with Japan securing its leading position in the Pacific.

The first six months were successful. Then came the summer of 1942 and the tide started turning against Japan. More and more, defeats were broadcasted to the Japanese public as victories. But as time passed, this tactic seemed increasingly untenable.

Two years later, Hirohito would order his subordinates to promise to the people of Saipan an equal spiritual status in the afterlife with that of soldiers who died in combat. He feared that the captured civilians would turn against him and become a powerful propaganda tool for the Allies. On the 1st of July, 1944, more than 1,000 civilians committed suicide.

By the end of the month, the Emperor had realized he had no clothes. He would still attend the Imperial Council meetings – during which he would, traditionally, remain silent – and brief with the state and military officials, most of whom were trying to persuade him to fight until the last man. The Soviet Union was threatening with invading Japanese positions in Asian mainland; Germany had surrendered and the Allies issued an ultimatum, the Potsdam Declaration, demanding unconditional surrender. Hirohito was looking for a way out.

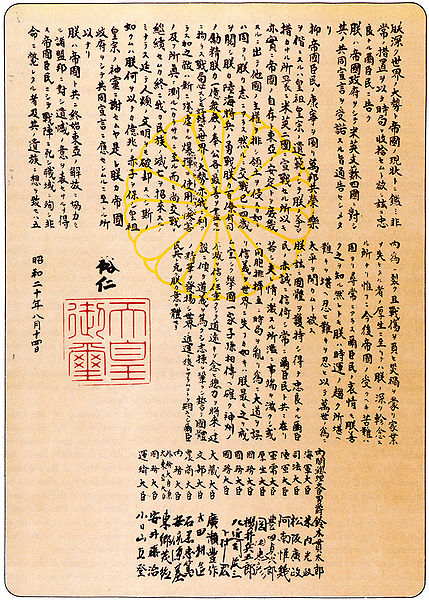

On August 9th, 1945, the US dropped the second atomic bomb, and the Soviets invaded the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo. A day later, Hirohito’s cabinet drafted the Imperial Rescript on the Termination of the War. On the night of 14–15th of August, a group of officers unwilling to surrender attempted a coup. For much of the night, they were occupying the Imperial Palace in an attempt to seize the recording of Hirohito reading the Rescript that was due to be played on the national radio the following day.

The coup attempt failed and the next day at noon, the Japanese got the chance to hear their Emperor’s voice for the first time. The speech was written in the formal, Classical Japanese, that few outside the ranks of nobility could readily understand. Hirohito famously called upon his “subjects” to endure the unendurable and suffer the insufferable and expressed great regret for the lives lost.

He never mentioned the word “surrender,” only that he had instructed the government to accept the Potsdam terms. This left many in confusion, so the radio broadcaster had to clarify the meaning of the Jewel Voice Broadcast speech after it was played. The record subsequently disappeared, but a radio technician managed to make a copy just in time. Later on, the original record was recovered but has never been played again. It all might have something to do with the fact that it was not easy for Hirohito to give up on one of the primary sources of his power – the claim that he was a descendant of the gods.

The US administration played a big role in maintaining Hirohito’s leading role in Japanese society after the war. The image of a distanced ruler, constrained by the prerogatives of religion and tradition, and persistently deceived by his war-mongering subordinates kept him away from the post-war crime tribunals. More recent historical explorations have offered a different picture of Hirohito – as an opportunistic leader who used exploited tradition as he pleased, with little care for the lives of his “subjects”.