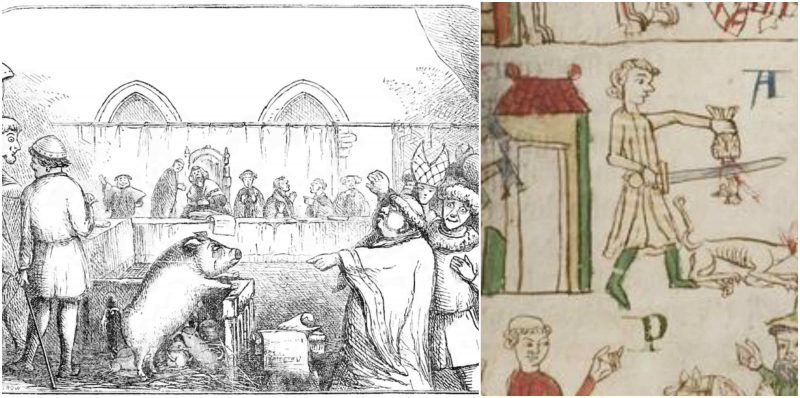

In modern times, you would be surprised to see a sheep or a cow dragged in front of a court to stand trial. However, during the Middle Ages and beyond, there was a lengthy legal tradition of calling animals to the stand.

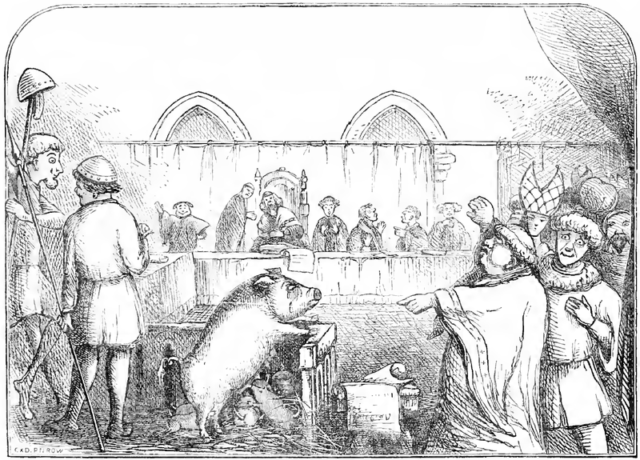

From the thirteenth century until the eighteenth, there are many recorded cases of animals in the courtroom. All kinds of creatures, from farm animals to insects, faced the possibility of criminal charges for several centuries across many parts of Europe. The earliest extant record of an animal trial is the execution of a pig in 1266 at Fontenay-aux-Roses. Such trials remained part of several legal systems until the 18th century.

Animal defendants appeared before both church and crown courts, and the offenses arrayed against them ranged from murder to criminal damage. Human witnesses were often called to the stand, and animals were routinely provided with lawyers in religious courts (this was not the case in secular courts, but for most of the period concerned, human defendants did not enjoy this privilege either). If convicted, it was usual for an animal to be exiled, or even executed. Yet some animals were able to win their freedom through the legal process. In 1750, a female donkey was acquitted of charges of bestiality due to witnesses to the animal’s virtue and good behavior. However, her human co-defendants were sentenced to death.

Translations of several of the most detailed records can be found in E.P. Evans’ The Criminal Prosecution and Capital Punishment of Animals, published in 1906. Sadakat Kadri’sThe Trial: Four Thousand Years of Courtroom Drama (Random House, 2006) contains another detailed examination of the subject. Kadri shows that the trials were part of a broader phenomenon that saw corpses and inanimate objects also face prosecution, and argues that an echo of such rituals survives in modern attitudes towards the punishment of children and the mentally ill.

Animals put on trial were almost invariably either domesticated ones (most often pigs, but also bulls, horses, and cows) or pests such as rats and weevils. Creatures that were suspected of being familiar spirits or complicit in acts of bestiality were also subjected to judicial punishment, such as burning at the stake, though few, if any, ever faced trial.

According to Johannis Gross in Kurze Basler Chronik (1624), in 1474 a rooster was put on trial for “the heinous and unnatural crime of laying an egg,” which the townspeople were concerned was spawned by Satan and contained a cockatrice.

Alleged werewolves were put on trial on several occasions, particularly in sixteenth-century France, though the allegation in such cases was always leveled against human defendants.