Oklahomans never thought that they would experience a funeral like his. Eighty years ago, the Oklahoma ranch boy that became legendary bank burglar Charles “Pretty Boy” Floyd was placed to rest in a little hilltop graveyard in Akins, approximately 10 miles northeast of Sallisaw, close to the Arkansas state boundary. It’s still believed to be the biggest funeral ever held in Oklahoma. Dust smoke rose as an uncontrollable crowd arrived. Counts of attendees ranging from anywhere between 10,000 and 40,000 people were projected, and a local newspaper reported that the roads leading to the rural graveyard were heavily congested that day.

Viewers for the afternoon affair, many of them carrying picnic lunches that they would later eat using tombstones as tables, cut off the cars of Floyd’s personal affiliates destined for the service. In reply, affiliates of the Floyd clan punched drivers in the face, and they shattered the camera of a woman who had climbed a tree by the funeral to snap a souvenir picture. The crowds approached in horse-drawn carriages and even a school bus, stated an Associated Press report. It was also reported that people trampled graves, crushed flowers, and as well kicked over stones in a hurry to view the body of Charles Arthur Floyd. Shockingly, also reported people were getting elbowed and pushed as they forced their way up to where the services were being held. A local man joining the burial noted most folks he saw at the service were from out of town, and countless journeyed from other states.

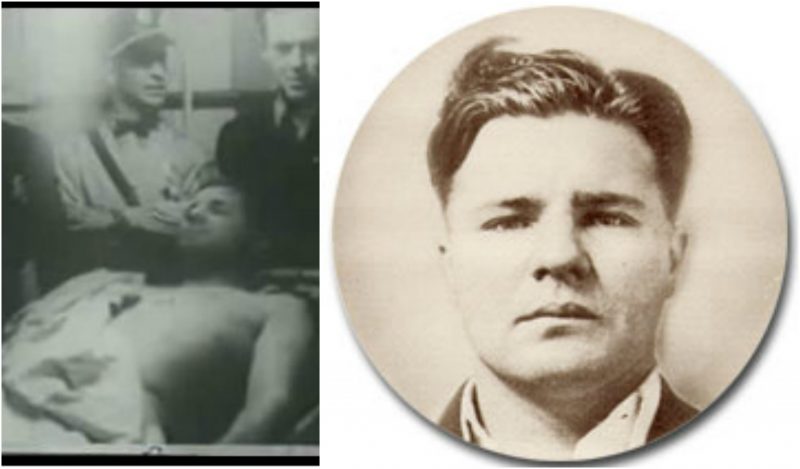

Federal agents had launched a hunt, dead or alive, for Floyd and his accomplices after the slaying of four law enforcement officers and a federal prisoner at the Union Station in Kansas City in June 1933. FBI agents killed Floyd on Oct. 22, 1934, in a shoot-out in a neighboring corn crib near East Liverpool, Ohio. He was 30 years old. At the moment of his death, he was being hunted in six states on charges of bank robbery and murder. As for the Union Station Massacre, Floyd claimed innocence with his last dying gasp, according to one account. To the folks of eastern Oklahoma, “Pretty Boy” was simply “Choc.” Despite their criminal feats, newspapers, magazines, and radio transmissions habitually glamorized Depression-era gangsters like Floyd. To some of the economically depressed Floyd was a Robin Hood rather than a notorious criminal. Maybe no one felt that more in their hearts then the masses of eastern Oklahoma.

Floyd’s Oklahoma origins run deep. Charles Arthur Floyd was the fifth of eight children, being born in Adairsville, Ga., on Feb. 3, 1904. The family ultimately decided to move in the early 1900s to Hanson, Oklahoma, and invested in cotton farming before settling down in Akins in northeastern Oklahoma. Family members stated that Floyd was a popular, pleasant youngster who excelled in basketball and track, according to an October 1984 statement in The Tulsa Tribune.

He would grow up to develop into one of the nation’s most famous outlaws. Family members stated he left Akins at the age of 18 to labor as a harvest hand in Missouri. Next, he moved to work at a St. Louis bakery. It’s rumored that is where he fell in with a ruthless influence. At 20, Floyd was involved in a $12,000 payroll robbery in St. Louis and was sentenced to five years in the Missouri state reformatory. Freed in 1929, he went back to Sallisaw and tried to get work in the oil fields from place to place in Seminole and Earlsboro. He was unable to get a job mostly because he had a criminal background. Incapable of finding steady work, he went to Kansas City and combined with ambitious bank robbers he’d encountered through prison acquaintances. Floyd was caught another time, along with two partners, after the 1930 bank theft in Sylvania, Ohio. Outside of Akron, submachine-gun fire from the escape car murdered a motorcycle patrolman who was chasing the gang. Floyd was cleared of the officer’s death but was condemned to 15 years in the Ohio state penitentiary in Columbus for the theft. During a relocation, he ran away by jumping through a train window.

Between 1929 and 1934, Floyd raided banks and consistently got away from the authorities attempting to stop him, forming new alliances as his companions left him. He frequently sheltered from the law in the Cookson Hills, where he lived his youth. He became known for his kindness, bestowing those who assisted him with cash. He also fed 12 families, according to the book, Life and Death of Pretty Boy Floyd, by Jeffery S. King. Hiding out in the caves and gorges and forests of the hills gave him the nickname “The Phantom of the Ozarks.” Part of the urban myth attached to Floyd is that he blackened farmers’ mortgages to stop banks from foreclosing – there is little to no proof of such events.

He lost hundreds of associates on April 9, 1932, when he murdered former McIntosh County Sheriff Erv Kelly, a famous peace officer. Kelly took Floyd by surprise as an accomplice, in part, for the $7,000 reward money. In Akins, followers of the funeral mass sought to catch a last sight of the phantom outlaw. It was rumored that when the hearse arrived to remove the body, sheriffs had to push the crowd away. Children and their mothers fainted because of the crowed and dusty environment. The last car left the burial ground long after dark had fallen. The tales of Floyd and his machine guns and fast cars will always be remembered. He will always be known as an old time fugitive who had robbed and flew, and took a gamble with the law no matter the cost.