Jan de Doot was a 17th-century Dutch blacksmith with bladder lithiasis. Despite having been treated twice by barber-surgeon lithotomists of the day, he continued to experience harrowing pain and dysuria. Dissatisfied with his prior experiences, he had no interest in seeking a lithotomist; rather, he devised a plan to extricate his own bladder stone, reasoning that any wild adventure was more attractive than… the knife of the stone-cutter.

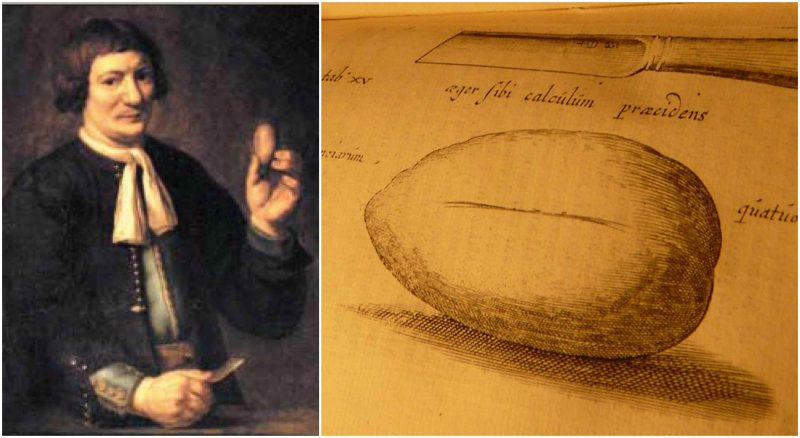

Jan de Doot is the subject of a painting from 1655 by Carel van Savoyen. It shows De Doot, a smith, holding in one hand a kitchen knife, and in the other a large bladder stone the size and shape of an egg, set in gold. The painting is part of the Portrait Collection of the Laboratory of Pathology, which is part of the University of Leiden.

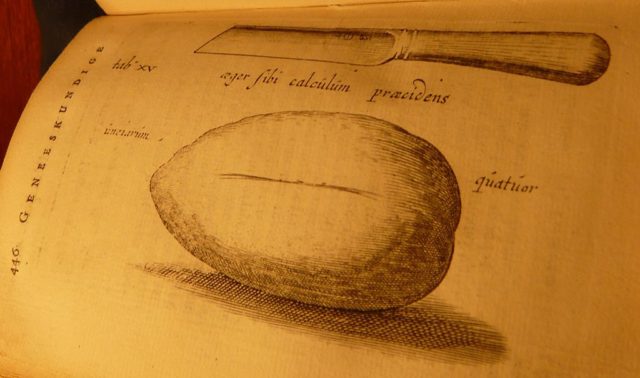

The story on which the painting is based is from Nicolaes Tulp’s book entitled Observationes medicae (1672 edition), and here is the text:

Observations, Book IV, Chapter 31. Wherein a patient cuts a stone out of himself.

“Joannes Lethaeus, a Smith, a courageous man, and very astute, who had already been treated twice by a stonecutter, desired so little to be treated a third time by such a man among his daily trials and repeated slayings, that he decided any wild adventure was more attractive to him than subjecting himself to the knife of the stonecutter ever again. Convincing himself that his health could only improve, and having decided that no one but himself would cut into his flesh, he sent his unknowing wife to the fish market. Only letting his brother help him, he instructed him to pull aside his scrotum while he grabbed the stone in his left hand and cut bravely in the perineum with a knife he had secretly prepared, and by standing again and again managed to make the wound long enough to allow the stone to pass. To get the stone out was more difficult, and he had to stick two fingers into the wound on either side to remove it with leveraged force, and it finally popped out of hiding with an explosive noise and tearing of the bladder.”

Now the more courageous than careful operation was completed, and the enemy that had declared war on him was safely on the ground, he sent for a healer who sewed up the two sides of the wound together, and the opening that he had cut himself, and properly bound it up; the flesh of which grew so happily that there no small hope of health was, but the wound was too big, and the bladder too torn, not to have ulcers forming.

But this stone weighing 4 ounces and the size of a hen’s egg was a wonder how it came out with the help of one hand, without the proper tools, and then from the patient himself, whose greatest help was courage and impatience embedded in a truly impenetrable faith which caused a brave deed as none other. So was he no less than those whose deeds are related in the old scriptures. Sometimes daring helps when reason doesn’t.”

According to the date of the portrait, he survived at least until 5 years after the book came out, but the Latin Lethaeus means “of the underworld” and Dutch de doot means “the death”, could also indicate that he had already died.