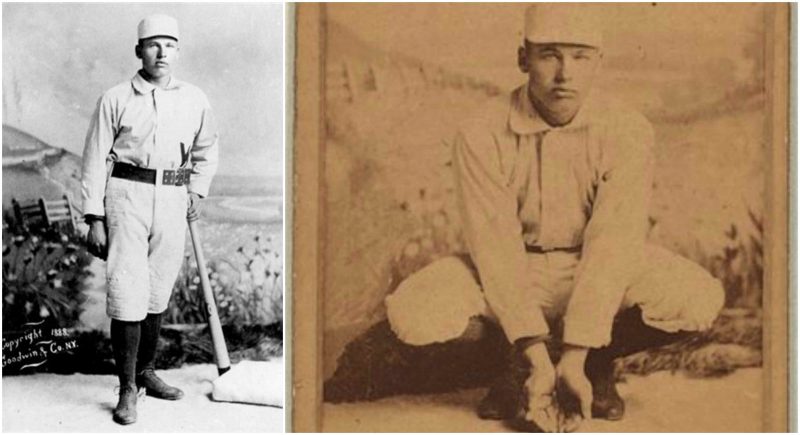

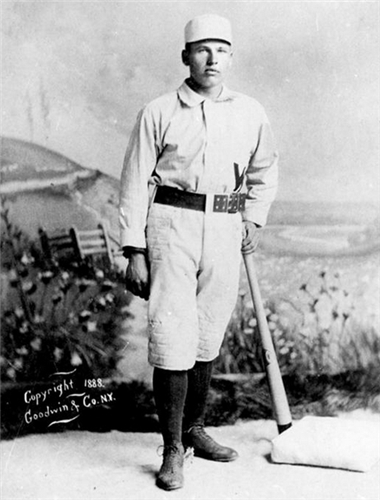

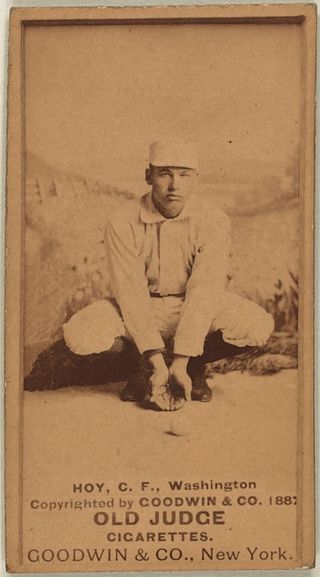

William Ho, better known as Dummy Hoy, is noted for being the most accomplished deaf player in Major League history and is credited by some sources with causing the establishment of signals for safe and out calls.

Born in the small town of Houcktown, Ohio, Hoy became deaf after suffering from meningitis at age three and went on to graduate from the Ohio State School for the Deaf in Columbus as class valedictorian. He opened a shoe repair store in his hometown and played baseball on weekends, earning a professional contract in 1886 with a Wisconsin managed by Frank Selee.

In 1888, with the Washington Nationals of the National League, Hoy became the third deaf player in the Major Leagues, after pitcher Ed Dundon and pitcher Tom Lynch. In his rookie year he led the league in stolen bases (although the statistic was defined differently before 1898), and also finished second with 69 walks while batting .274. At 5’4″ and batting left-handed, he was able to gain numerous walks with a small strike zone, leading the league twice and compiling a .386 career on-base percentage.

Hoy’s speed was a significant advantage in the outfield, and he was able to play shallow as a result. On June 19, 1889, he set a Major League record (which has since been tied twice) by throwing out three runners at home plate in one game, with catcher Connie Mack recording the outs. He and Mack joined the Buffalo Bisons of the Players’ League in 1890, after which Hoy returned to the AA with the St. Louis Browns under player-manager Charles Comiskey for the league’s final season in 1891, leading the league with 119 walks and scoring a career-high 136 runs (second in the league). He returned to Washington for two years with the Washington Senators of the National League and was traded to the Reds in December 1893, where he was reunited with Comiskey.

Hoy later joined the Louisville Colonels, where his teammates included Honus Wagner, Fred Clarke and Tommy Leach (who was his roommate), and he hit .304 and .306 in his two seasons with the club. In 1899 he broke Mike Griffin’s Major League record of 1459 games in center field.

After playing for the Chicago White Sox in the American League during its last minor league season in 1900, where Comiskey was now the team owner, Hoy stayed with the team when the AL achieved Major League status in 1901, helping them to the league’s (and his) first pennant. That year he broke Tom Brown’s record of 3623 career outfield putouts, and also led the league with 86 walks and 14 times hit by pitch while finishing fourth in runs (112) and on-base percentage (.407).

He ended his Major League career with the Reds in 1902, batting .290 and breaking Brown’s record of 4461 career total chances in the outfield, and played for Los Angeles in the Pacific Coast League in 1903. In May of his last season with the Reds, he batted against pitcher Dummy Taylor of the New York Giants in the first faceoff between deaf players in the Major Leagues; Hoy got two hits.

Hoy retired with a .287 batting average, 2044 hits, 1426 runs, 726 runs batted in, 248 doubles, 121 triples, and 40 home runs. He had 487 stolen bases from 1888 through 1897, and 107 more after the statistic was redefined to its present meaning in 1898. His 1795 games in the outfield ranked second to Jimmy Ryan (then at 1829) in Major League history. Jesse Burkett broke his Major League record for career putouts in 1905, and Clarke topped his record for career total chances in 1909. His record for career games in center field was broken by Tris Speaker in 1920.