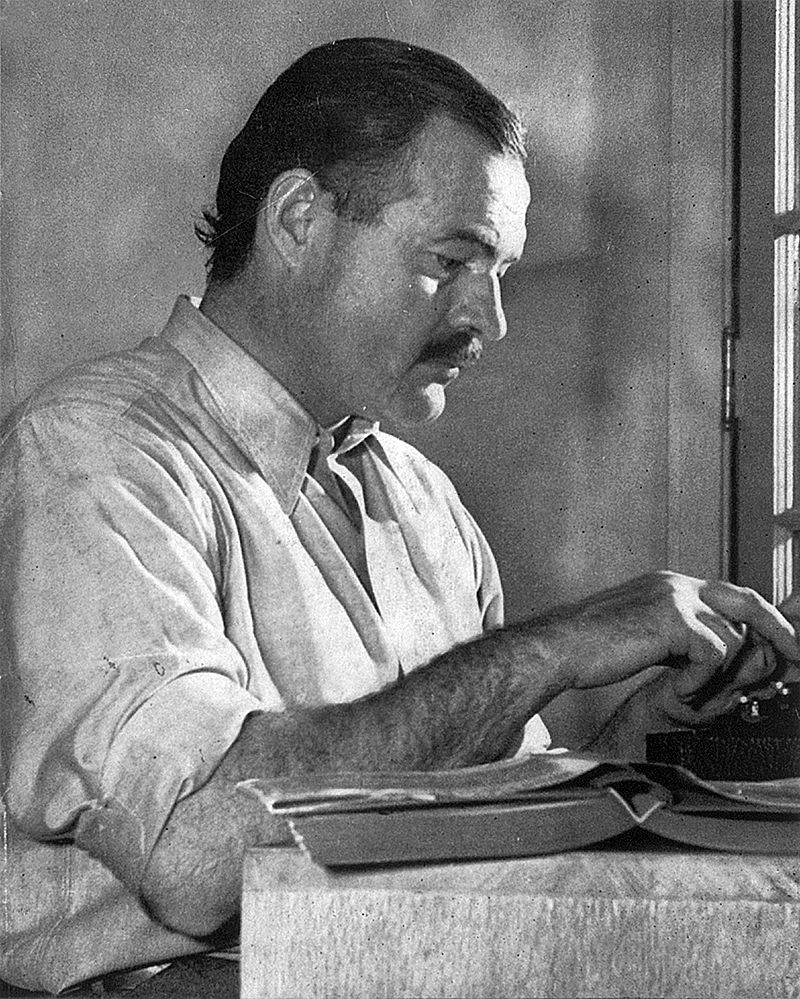

Ernest Hemingway, born on July 21, 1899, was one of the best American authors of all time and a man of many talents. In the last years of his life, he developed severe paranoia. He said that the FBI was watching his every move and he told his friends that they bugged his car and were reading his mail. But what reason could the FBI have to spy on Ernest Hemingway?

The answer to this question came in the year of 2010 when Yale Univerity Press released a book called Spies: The Rise and Fall of the KGB in America. The book was co-written by John Earl Haynes, Harvey Klehr, and Alexander Vassiliev and it reveals that the Nobel Prize winner was on a list of the KGB’s agents in America.

It seems that the FBI had a legitimate reason to investigate Hemingway. The information revealed in the book was based on KGB archives to which one of the co-writers of the book, Alexander Vassiliev, gained access after the end of the Cold War. And yes, no matter how surprising it seems, Ernest Hemingway was working for Mother Russia. His spy skills weren’t as good as his writing skills but still, he tried using them.

It’s revealed that he met Soviet agents in Havana and London and was also given a code name. They called him “Argo.” During the meetings, he repeatedly expressed his desire and willingness to help.

He was determined to become a spy during World War II and he contacted four governmental entities. One was the American embassy in Cuba, the second was the Office of Naval Intelligence, the third was the Office of Strategic Services and the fourth was the NKVD, a forerunner of the KGB. So he worked as a double agent for the Americans and the Russians from 1941-1943.

Together with the U.S. ambassador in Cuba, Spruille Braden, they created an informal intelligence service in Havana – “The Crook Factory.” The service was supposed to monitor communists and fascist sympathizers but the service was seen by the FBI as an amateur group.

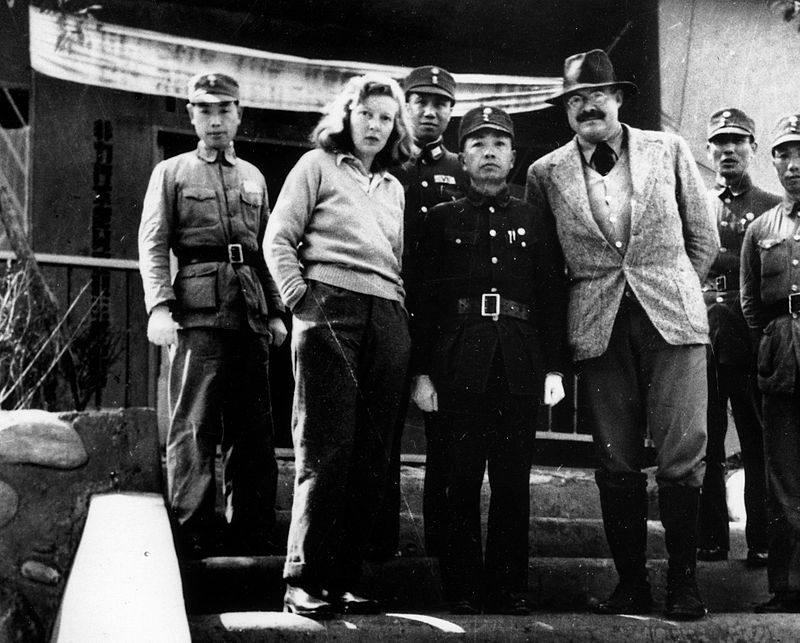

Later, Hemingway was asked if he could gather intelligence in China, and in the company of his third wife Martha Gellhorn he went east. There he gathered intelligence by meeting communist leaders and other government officials. He gave the information he gathered during his stay in China to Harry White, who was revealed to be an agent working for the KGB. So all of the intelligence gathered in China ended up in Russian hands.

Hemingway probably didn’t know that White was working for the KGB, but it seems that the Russians liked Hemingway and they attempted to make multiple deals with him. It’s revealed in the book that Hemingway always agreed to work with the Russians, but he never came up with valuable information for them.

Ernest Hemingway took his own life in 1961 when he was 61 years old. No one knows what drove the Nobel Prize winner to suicide. It might be the money issues he had or problems with his family life. He was extremely paranoid and depressed in his final years. He believed that FBI was constantly following him but no one took him seriously.

It’s clear that Hemingway loved espionage and was probably looking for inspiration to write while he was spying, but it seems espionage may have led him to an early death.