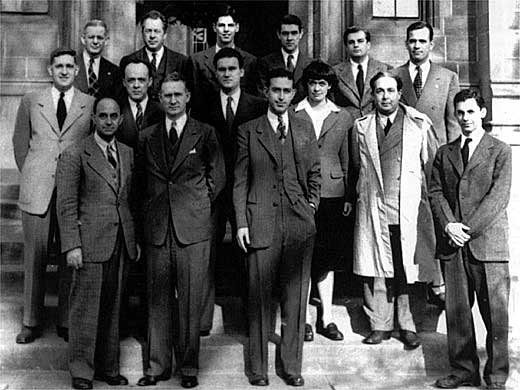

In 1944, the U.S. pinned its hopes on a secret project to win World War II. An integral part of this project was Leona Harriet Woods, later known as Leona Woods Marshall Libby. At age 23, she was the youngest physicist and only female member of the team which built and experimented with the world’s first nuclear reactor Chicago Pile-1, in a project led by her mentor Enrico Fermi.

Leona was a super-genius born in 1919 in La Grange, Illinois. By the time she was fourteen, she’d graduated high school, and she finished college at the University of Chicago at the ripe old age of eighteen.

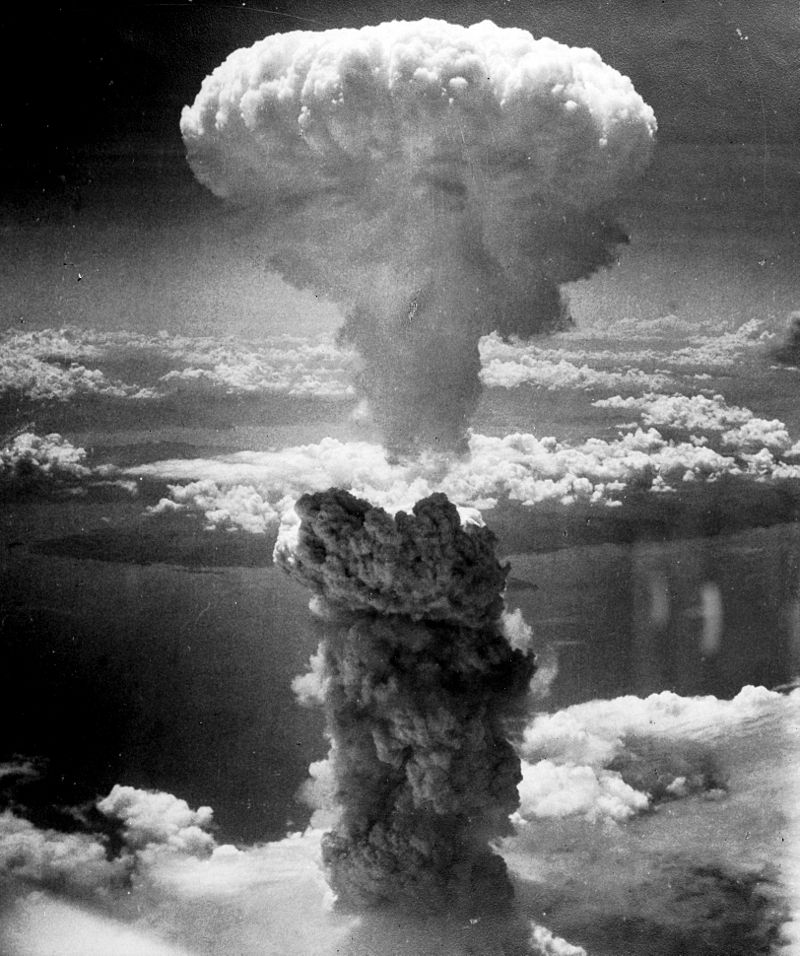

All the scientists working against the clock were trying to build the bomb before the Nazis could. Leona was the only woman present when the reactor went critical. She worked with Fermi on the Manhattan Project, and, together with her first husband John Marshall, she subsequently helped solve the problem of xenon poisoning at the Hanford plutonium production site and supervised the construction and operation of Hanford’s plutonium production reactors.

Despite working long hours with ultra-dangerous fissionable materials, Leona Woods also found time to head over to her family farm and help her mom take care of that year’s potato crop.

Leona earned her Ph.D. a year after the first successful nuclear test, and got married soon after. She was pregnant while she worked on a second nuclear reactor and she was afraid that if someone knew about it that she would be forced to leave the project, so she wore baggy clothes and kept it a secret.

After many years she was asked how she felt for being involved in a project like that she said: “I think everyone was terrified that we were wrong (in our way of developing the bomb) and the Germans were ahead of us. That was a persistent and ever-present fear, fed, of course, by the fact that our leaders knew those people in Germany. They went to school with them. Our leaders were terrified, and that terror fed to us. If the Germans had got it before we did, I don’t know what would have happened to the world. Something different. Germany led in the field of physics. In every respect, at the time war set in, when Hitler lowered the boom. It was a very frightening time.”

When the war was over she returned and worked at the university of Chicago there she become an assistant professor in 1953. In her career, she published more than 200 scientific papers. She died on November 10, 1986.