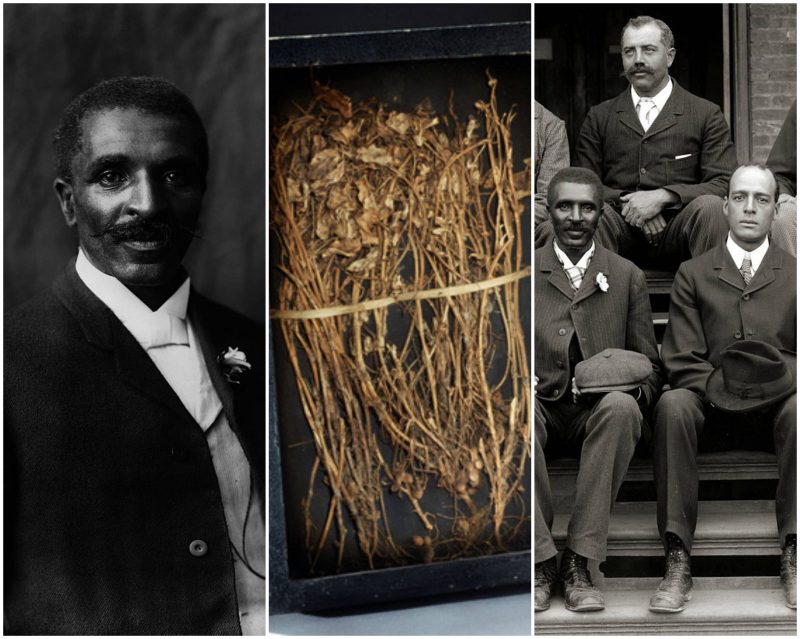

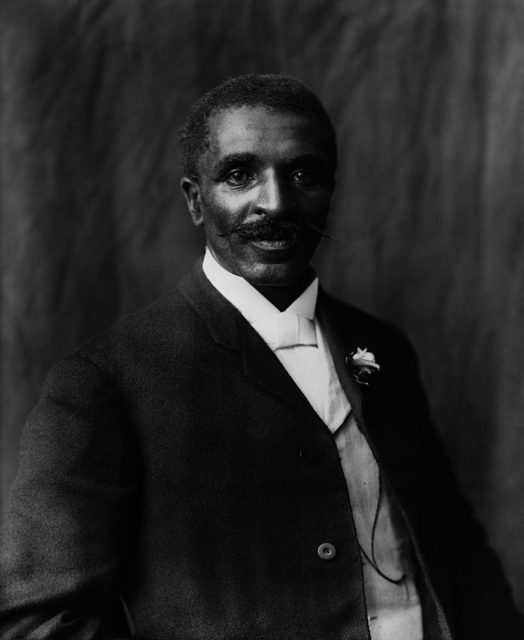

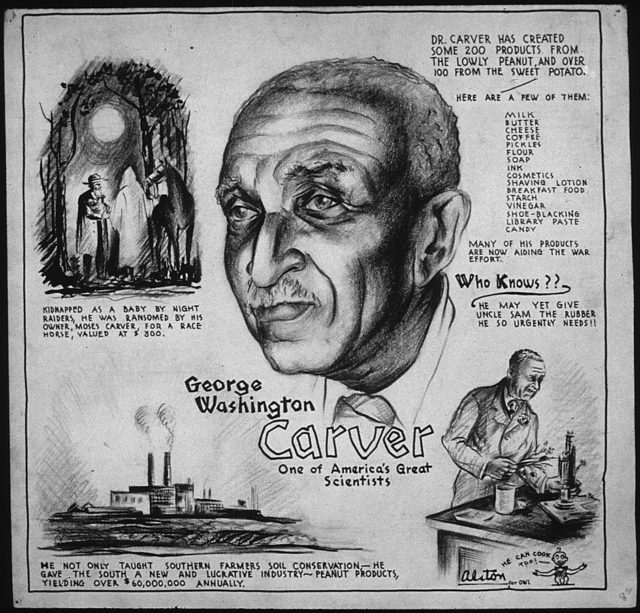

The African-American scientist and inventor George Washington Carver is best known for his 300 uses for peanuts. The prominent inventor was also responsible for introducing the idea of crop rotation to southern US farmers, a method of growing various types of crops in a certain area in sequenced seasons. A humanist above all, his work and contribution to science demanded no money and many of his inventions and ideas went unpatented.

He was born in Diamond, Missouri, around the 1860s to Mary and Giles, whom their master, Moses Carver, bought as slaves. His father was killed in a farming accident and George was kidnapped by Confederate raiders. Carver found the raiders and they demanded money for his return. Carver bought him back, along with his older brother James. Moses Carver didn’t have children, so he and his wife raised the two boys as their own.

Carver’s wife, Susan, taught the children to read and write, and since George was a frail child he was not strong enough to work in the fields, he participated in less-demanding work in the garden, tending the flowers and plants, and making simple herbal medicine. He was fascinated by animals and plants and the local farmers dubbed George “the plant doctor”, since he was very skilled in improving the health and life of their garden plants.

At the time, it was hard to find a school that would accept African-American children, and George was forced to walk 10 miles just to attend the School for African American Children in Neosho. He paid for his high school tuition fees working in the kitchen of a local hotel in Minneapolis and participating in local baking contests.

George Carver applied to the Highland Presbyterian College in Kansas and they were very impressed by his application essay, granting him a full scholarship. Sadly, he was turned away when he arrived, since the school didn’t know he was black. He started working a variety of jobs to save the money to go to a college that would accept him.

He was enrolled as the first black student at Simpson College in Iowa in 1888, and he liked it there, saying, “The kind of people at Simpson College made me believe I was a human being.” He quickly began studying art and piano, hoping he would earn a teaching degree. Noticing his skill and attention to detail in his drawings of plants, a teacher named Etta Budd encouraged him to apply to Iowa State Agricultural School to study botany, where he would earn his Bachelor of Science in 1894, and later, his master’s degree in 1896.

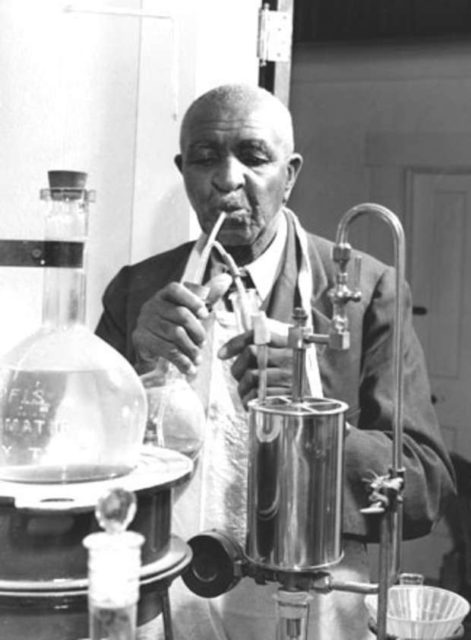

While he was working as a director of the Iowa State Experimental Station, he discovered two types of fungi, which were named after him. It is then that Carver began experimenting with crop rotation and using soy plantings to replace nitrogen in barren soil. Before long, Carver became well known as a leading agricultural scientist.

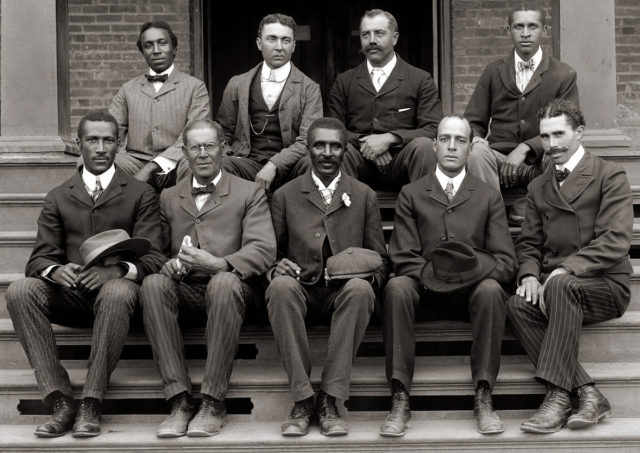

Carver’s rise to recognition began when he received a letter from Booker T. Washington in April 1896. He was from the Tuskegee Institute, which was one of the first African-American colleges in the United States. The letter read: “I cannot offer you money, position, or fame. The first two you have. The last from the position you now occupy you will no doubt achieve. These things I now ask you to give up. I offer you in their place: work – hard work, the task of bringing people from degradation, poverty, and waste to full manhood. Your department exists only on paper and your laboratory will have to be in your head.”

He offered Carver 125 dollars per month, along with accommodation in two rooms for living quarters. This was a luxurious offer, since most Tuskegee faculty members only had one room and Carver lived and worked here for the rest of his life.

As a child of slaves, Carver has seen the horrors and toil of the workers and his concern was helping out the poor farmers of the rural south. His crop rotation method proved to be a life-saving idea, with many acres of peanut and cotton crops flourishing. Peanut is a simple seed to grow, with properties that improve the soil which was depleted by growing cotton.

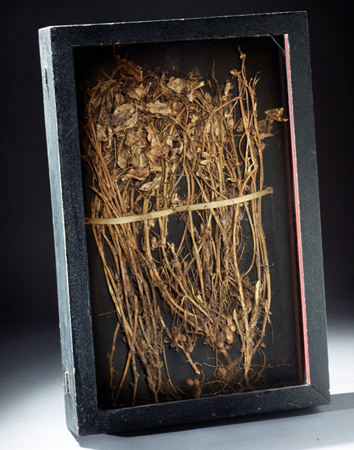

The rural farmers were very pleased with the result, but complained about the huge surplus of peanuts that went to waste and rot in the stores. So, to thwart the huge pile-up of peanuts, he began to search for practical uses for the plant. He developed flour, paste, paper, soap, shaving cream, medicine and countless more peanut-based products in his Jessup Wagon (a horse-drawn lab for soil chemistry). Carver introduced the myriad of products in simple-to-read brochures. The peanut market skyrocketed, as many people were fascinated by the peanut inspired products, making Carver an agricultural hero of the South.

Contrary to popular belief, Carver did not invent the famous peanut butter, even though he made a version of it. The Incas were the first to make a paste from ground peanuts in around 950 B.C. and in the United States, according to the National Peanut Board, Dr. John Harvey Kellogg (known for the cereal) had invented his own type of peanut butter in 1895. Oddly enough, an unknown doctor from St. Louis may have developed peanut butter for people that couldn’t chew hard foods, introducing the product at the 1904 Saint Louis World Fair.

During World War I, Carver was asked to assist Henry Ford in producing a peanut-based replacement for rubber. Also during the war, dyes were difficult to get in Europe so he helped the American textile industry by developing more than 30 colors of dye.

After the War, George added the letter “W” to his name to honor Booker T. Washington. Carver continued to experiment with his peanut products and began to experiment with sweet potatoes and other seeds. He even went to India to confer with Mahatma Gandhi on nutrition in developing nations.

The humble inventor’s actions throughout his life showed his disinterest in money, with him at one point turning down a six-figure job offer from Thomas Edison.

In his life, Carver only patented three of his inventions, believing “It is not the style of clothes one wears, neither the kind of automobile one drives, nor the amount of money one has in the bank that counts. These mean nothing. It is simply service that measures success.”

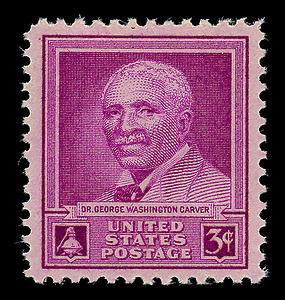

Carver died on Jan. 5, 1943. He left his $600.000 savings to fund the building of the George Washington Carver Institute for Agriculture at Tuskegee. In 1943, President Franklin D. Roosevelt erected a monument to honor his contribution at Diamond, Missouri. Commemorative postage stamps were issued in 1948 and in 1998, as well as George Washington Carver half-dollar coins that were minted between 1951 and 1954. Congress has designated January 5th as George Washington Carver Recognition Day.

Today, George Washington Carver is an icon of American ingenuity and agricultural insight. The integrity of the modest method he held with his inventions, along with his profound faith in God, is the sole essence of his contribution to agricultural science. He stated: “One reason I never patent my products is that if I did, it would take so much time I would get nothing else done. But mainly I don’t want any discoveries to benefit specific favored persons. I think they should be available to all peoples.”