Early in the 19th Century, it was extremely fashionable for Europeans to collect wild animals from around the world, bring them home and put them on display like in a museum.

A French dealer decided to take that one step further by bringing home the body of an African warrior. Frank Westerman, a Dutch writer, came across the exhibit in a Spanish museum 30 years ago. He was determined to trace the man’s history.

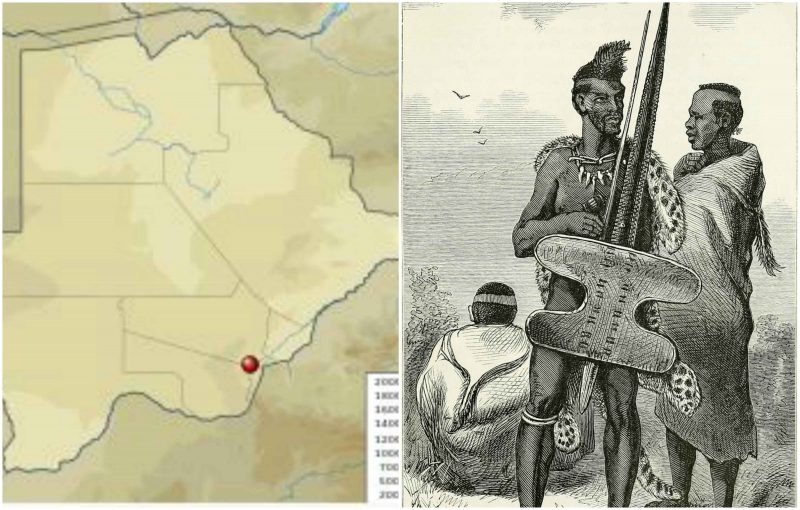

Blue, white and black, the national colors, decorated a chain link fence that marked the grave of one of the most famous and least enviable sons of Botswana: “El Negro”.

In a tomb, the likes of an unknown soldier, is his resting place in a public park in the city of Gaborone, which is under a trunk of a tree with some rocks on top.

There is a metal plaque that reads:

El Negro

Died c. 1830

Son of Africa

Carried to Europe in Death

Returned Home to African Soil

October 2000

Traveling as a museum exhibit for 170 years, throughout France and Spain, all of El Negro’s fame comes to him posthumously, unfortunately.

Exhibited like a trophy, there he stood, nameless, half naked, stuffed and mounted by a taxidermist, while generations of Europeans gaped at him.

“Back in 1983, as a university student from The Netherlands, I accidentally came across him on a hitchhiking trip to Spain. I had spent a night in the town of Banyoles, an hour north of Barcelona.

The entrance of the Darder Museum of Natural History, behind a trio of leafless plane trees, happened to be next door,” Westerman remembers.

“He’s real, you know,” a schoolgirl shouted at me.

“Who’s real?”

“El Negro!” Her voice blared out over the square – accompanied by the snorts and laughter of her friends.

“The next instant an elderly woman stepped out of the hairdressing salon with a cardigan draped over her shoulders. A fragile lady with a pointy chin graced by a few single hairs, she turned a key ring around in her fingers like a rosary. Senora Lola opened up the museum, sold me a ticket and pointed in the direction of the reptile room.”

“That way,” she ordered. “Then go through the rooms clockwise.”

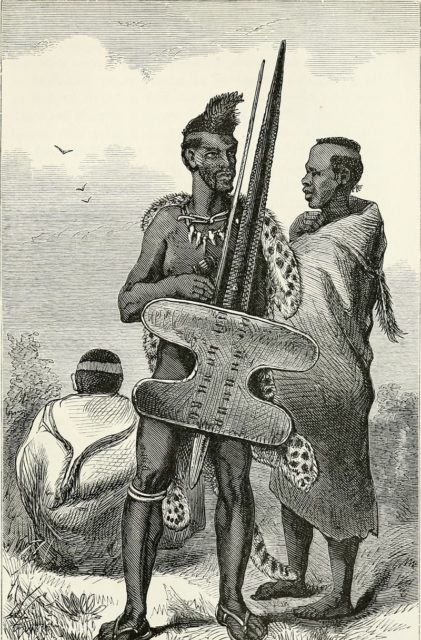

“As I was on my way to the Human Room, an annex of the Mammal Room, past a climbing wall with apes and the skeleton of a gorilla, my merriment gave way to a shudder. There he was, the stuffed Negro of Banyoles. A spear in his right hand, a shield in his left. Bending slightly, shoulders raised. Half-naked, with just a raffia decoration and a coarse orange loincloth.”

“El Negro turned out to be an adult male, skin and bones, who hardly came up to one’s elbow. He was standing in a glass case in the middle of the carpet.”

“This was not Madame Tussaud’s. I was not staring at an illusion of authenticity – this black man was neither a cast nor some kind of mummy.

He was a human being, displayed like yet another wildlife specimen. History dictated that the taxidermist was a white European and his object a black African. The reverse was unimaginable. I flushed and felt the roots of my hair prickling – simply from a diffuse sense of shame.”

“Senora Lola didn’t have an explanation. She didn’t even have a catalogue or a brochure. She tapped a carousel postcard stand and stared at me through her glasses. I took a card of El Negro and read on the back: Museo Darder – Banyoles. Bechuana.”

“Bechuana?”

Senora Lola kept staring at me. Head back, chin jutting forward. “The cards are 40 pesetas each,” she said.

I bought two.

“Twenty years later I decided to write a book about El Negro’s extraordinary journey from Botswana (Bechuana) to Banyoles and back again.”

As the story begins, Jules Verreaux, a French dealer, who in 1831 witnessed the burial of a warrior from Tswana, in the African interior just a few days travel north of Capetown, and then went back at night- “not without danger to my own life”, says Verreaux-to dig up the body so he could steal the skin, some bones and the skull.

After digging up the body, Verreaux, prepared the body with the help of metal wire acting as a spine, boards acting as shoulders and then stuffed the body full of newspapers.

He then shipped the body to Paris along with some stuffed animals in the crates. In a showroom at No. 3, Rue Saint Fiacre is where the African’s body first appeared for viewing.

The newspaper, Le Constitutionnel, praised the fearlessness of Verreaux, stating that he must have faced grave dangers “amid natives who are as wild as they are black”.

This article set the tone, and the “individual of the Bechuana people” attracted more attention than the giraffes, hyenas or ostriches. “He is small in posture, black-skinned, and his head is covered in woolly frizzy hair,” the newspaper said.

More than 50 years later, the “Bechuana” showed up in Spain. The Spanish vet, Francisco Darder listed the warrior in a brochure as “El Betchuanas”, with a drawing in which he is seen wearing raffia finery ad holding a spear and shield. This was at the onset of the world exhibition in Barcelona in 1888.

Banyoles, a small city at the foothills of the Pyrenees, was where the warrior ended up by the 20th Century. By this time his origins at all but been forgotten-on the pedestal was mistakenly written “Bushman of the Kalahari”.

As the decades progressed, the link to his Tswana origins faded even further, and he became simply, “El Negro”.

Somewhere along the way, the revealing loincloth Verreaux had put on him was replaced by the Roman-Catholic curators of the Banyoles museum with a mere orange skirt. They covered his skin in shoe polish to make him seem blacker than he was.

Within the display case, with a piercing gaze and slightly bowed, El Negro was embodied in a poignant and harrowing way, the darkest parts of Europe’s colonial past.

El Negro knocked visitors in the face with theories of “scientific racism”-the classification of people according to their supposed inferiority or superiority on the basis of skull measurements and other false assumptions.

Moving forward through the 20th Century, El Negro became a much larger anachronism. There was not only increasing awareness and guilt over the fact that his grave and then body had been violated, but as a 19th Century European artifact, he reflected ideas that had become unsound.

In 1992, things began to shift when a Spanish doctor of Haitian origin suggested in a letter to El Pais that El Negro needed to be removed from the museum.

That year the Olympic Games were coming to Barcelona, and the lake of Banyoles was to be used for the rowing competitions. Dr. Alphonse Arcelin wrote, “Surely the athletes and spectators who visited the museum would take offense at the sight of a stuffed black man”.

Arcelin’s letter was supported by prominent names such as the U.S. pastor Jesse Jackson and basketball legend “Magic” Johnson. The Ghanaian Kofi Annan, then still Assistant Secretary-General of the UN, condemned the exhibit as “repulsive” and “barbarically insensitive”.

Because of heavy resistance by the Catalan people who embraced El Negro as a “national” treasure, it was not until March 1997 that El Negro disappeared from public viewing and “Object 1004” was put into storage.

In the autumn of 2000, three years later, El Negro began his final journey home.

After many long consultations with the Organization for African Unity, Spain agreed to send back the human remains to Botswana for a ceremonial reburial in his native African soil.

The first part of his return to Botswana was a ride in the middle of the night in a truck to Madrid.

In the capital of Spain, his stuffed body was stripped of all the non-human items he had on, such as the glass eyes. El Negro was stripped- as if the film of the preparations that Jules Verreaux carried out 170 years earlier was simply rewound.

However, his skin turned out to be hard and crusty-it crumbled. Due to this and because of the shoe polish that had been applied, they decided to keep the remains in Spain. One newspaper reported he was left behind at the Museum of Anthropology in Madrid.

Only the skull and certain arm and leg bones were all that was in the coffin bound for Botswana.

In the capital of Gaborone, the remains of the Tswana warrior lay in state for one day where an estimated 10,000 people walked past to pay their respects.

The next day, October 5, 2000, he was committed to earth for the second time in a fenced off area in the Tsholofelo park, BBC News reported.

They had a Christian burial with a priest that said: “In the spirit of Jesus Christ, who also suffered. We are prepared to forgive,” said the then-Foreign Minister Mompati Merafhe to the assembled mourners. “But we must not forget the crimes of the past, so that we don’t repeat them.”

Supported by two rows of tent poles, an awning covered to the guests of honor from the sun. After the blessings were concluded, there was singing and dancing and buglers wearing white gloves that sounded the last salute.

After all the tributes were paid, the grave sat neglected for many years, the field around it being used for football. Recently, the Botswanan government has restored and enriched the site with a visitor’s center and signs that explain things.

As of today, it is still not known who this “son of Africa” is-what was his name, or where exactly did he come from?

In a Catalan hospital, an autopsy was performed in 1995, and it brought several things too light that we previously did not know or even consider.

The man who became world-renowned as El Negro lived to be about 27 years old. When he was alive, he stood between 4ft 5in and 4ft 7in and he probably died of pneumonia.