People have always had a fear of so-called witches. Of course, witches are not even remotely real, but that didn’t stop people from punishing innocent women for doing “witch-like” things. Take a look at the Salem witch hunters and trials, where many innocent women died.

Just recently, researchers believe they have uncovered an ancient grave that had belonged to a so-called witch. They had uncovered an unusual grave that containing a Neolithic skeleton; the remains show that the woman was once very deformed. The grave was found on a small Scottish island in the Hebrides.

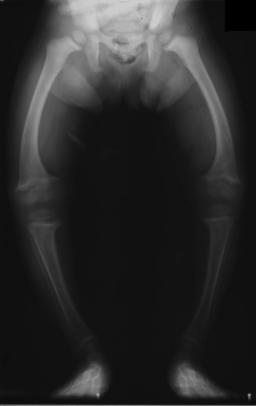

Researchers said that her remains reveal the woman had rickets in the breastbone, arms, ribs, and legs. Lead archaeologists went as far as saying this woman may have had one of the earliest cases of vitamin D deficiency ever found in the United Kingdom.

What is most interesting to the experts is that the woman had lived in an outdoors fishing community, meaning she should not have had the condition as severely as she did.

Other experts suggested that she could have worn heavier clothing or even a costume that had prevented her soaking up sunlight. This may have been because she was either a slave who didn’t have a choice or she was a special member of the community who had a religious of spiritual significance.

Although her remains piqued the experts’ interest, her simple grave also interested them. Instead of being buried in a chambered tomb, the woman had been buried in the ground with a small section of stones for a marker.

The only funerary offering she had been given was one white quartzite pebble.

Because she had such a small, basic burial, archaeologists believe she must have had a very low status in the community. This raises questions among experts as to whether or not she was mistreated by the community members due to her deformities.

The bones had been excavated from the site in a northwestern village called Balevullin on the Scottish island, Tiree. Archaeologists believe that the woman had been around the age of 25 to 30 years old when she died. The skeleton showed that she was most likely four feet, nine inches tall.

Surprisingly, by Neolithic standards, she had been very short – the average Neolithic woman was about five feet, five inches.

She would have appeared to have a pigeon chest with misshapen limbs and a hunched position. This would explain why she was so crunched in her grave.

Her body was found with three other burials back in 1912. However, her bones were finally just analyzed by Professor Ian Armit and his team from the University of Bradford and Durham.

When the site was first excavated, experts believed she had belonged to the same period as the nearby Iron Age settlement found. However, thanks to radiocarbon dating it was revealed that she was from a much earlier period. It dated the remains to about 3340 to 3090 BC, placing her during the Neolithic period.

Up until now, the earliest case of rickets in Britain had been found to be from the Roman period. This new find predates the Roman period by 3,000 years. An analysis on her teeth offered clues about her diet, especially as a child.

Due to the changing levels of carbon and nitrogen isotopes, the test showed the woman had suffered from physiological stress as a child. Otherwise, she suffered malnutrition or was quite ill between the ages of 4 to 14 years old.

The tests revealed that she had been part of the local area due to her higher strontium levels. This was a key characteristic of the ancient communities who had lived on the islands.

Because they lived on the island, the community members would have spent a majority of their time outdoors, providing a good amount of fish as their daily diet. Surprisingly, the woman had never eaten fish, or at least not enough to provide her with enough vitamin D to prevent her from getting rickets.

Researchers wonder how a person could have contracted rickets while living on Tiree, especially during the Neolithic period. They added that in this community’s case, the vitamin D deficiency should not have been a problem for anyone, as they would all have been especially exposed to the outdoors.

It is possible she had a genetic condition which didn’t allow her to retain the vitamin D, but that seemed to be a rare condition.

There are two ways the woman might not have been able to get the sunlight – either she had been kept indoors during her childhood and much or her life, or she had chosen to wear heavy clothing that didn’t allow the sunlight to absorb into her skin.

If she did happen to have an illness as a child which led to deformity, her parents most likely kept her indoors so the community members couldn’t see her, leading to a worsening of her illness.

It is also possible that she had a religious role that required her to stay in the dark or inside the shelter. However, if she was seen as a religious figure, it was most likely she would have had a more elaborate grave.

Because of these factors, it’s believed she was most likely seen as a witch or otherwise feared by other members of the community. If this was the case, she might have worn a costume to hide her deformities and face, or she may have been a slave who was not allowed outdoors.

The researchers said that it is too early to pinpoint what exactly happened to her and what kind of status she held when she was alive. They hope to keep analyzing the remains in order to get a more accurate sense of her life and death.