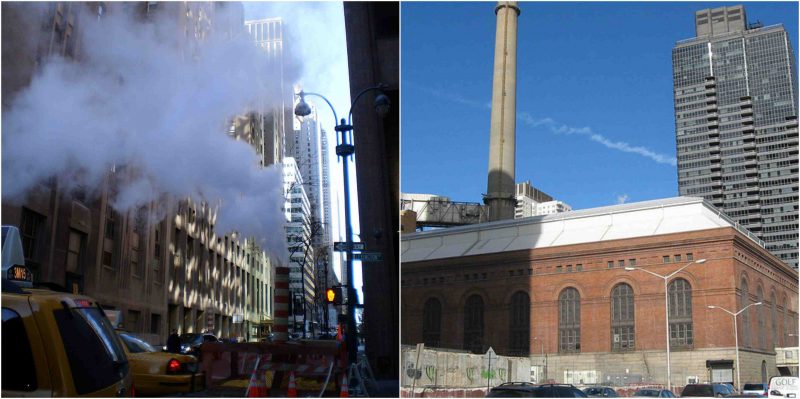

Walking around in New York City is certainly an adventure for the senses – the smells and tastes of food, the sound of taxi horns, the feel of pavement, and the sights of skyscrapers and huge digital billboards can be both exhilarating and overwhelming. A common sight in the city’s landscape seeps up from below the well-traveled streets, however, in the form of billowing steam clouds.

The sight of this steam is familiar to residents but can often be confusing to outsiders. Where is the steam from, and is it clean or dirty? The answers to these questions are intriguing and very much a part of the city’s past and present infrastructure.

The New York City steam clouds typically rise from manhole covers in the streets or from noticeable orange and white tubes. It is made of clean water and comes from a giant network of underground steam pipes. Con Edison is the company that operates the New York City steam network, which is bigger than the next nine largest steam systems put together and has more than double the steam production of the largest European steam network in Paris.

The steam that runs through the pipe system is approximately 350 degrees Fahrenheit, and the steam clouds that are seen above ground usually do not come from steam produced through the pipes by Con Edison. The plumes locals and tourists see result from water falling on the pipes from above and steaming up. Thus, the steam clouds are fuller in winter when rain and snow fall into the manholes.

When steam does leak and the pipes need repairs, maintenance workers employ prominent orange and white tube chimneys to protect passersby from steam burns and to stop it from interrupting the flow of traffic.

The New York steam system began in the late 1800s with 350 customers. It expanded to 100,000 residential and commercial customers at its peak in the 1920s and 30s. Today, the Con Edison steam network supplies steam to about 2,000 city buildings including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Empire State Building, and the United Nations headquarters.

It runs 105 miles from New York City and heats up water, keeps buildings warm, and powers cooling systems in the summer to reduce some of the city’s demand for electricity. The use of steam is cleaner and more efficient than having each building operate its own boiler system. If buildings had individual boiler systems, the skyline of Manhattan would be dotted with smoking chimneys, drastically altering its famous appearance.

Con Edison has five steam power plants throughout New York. Giant boilers make the steam that gets carried from the plants through the underground pipe network to customers. Eight pounds of steam can be made from a single gallon of water. In the winter, up to eight million pounds of steam can be generated each hour for New York City customers.

The use of steam in New York City is interesting, but underground steam networks cannot be provided everywhere. There are a demanding infrastructure and high operating costs are involved in the production, which makes more sense for large, dense cities that can both use the steam efficiently and afford to keep the power plants and pipe systems in service, CityLab reported.

Read another story from us: The spectacular engineering behind New York’s water supply

Those passing through New York City need not be concerned. The mist and clouds rising from below the busy streets are naturally safe water that residents use every day. However, it would be wise to stay away from those orange and white chimneys.