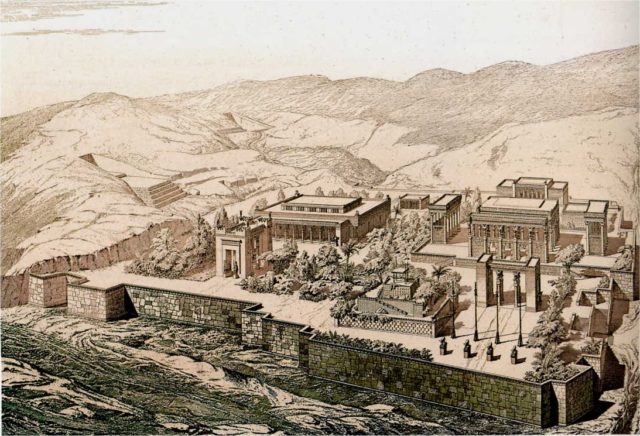

Persepolis, literally meaning, “The city of the Persians” served as a ‘ceremonial capital’ within the Achaemenid Empire, in the period between 550 and 330 BC. The empire was one of the largest in ancient history, based in Western Asia, but at its greatest extent reaching to the Balkans on the west and India on the east.

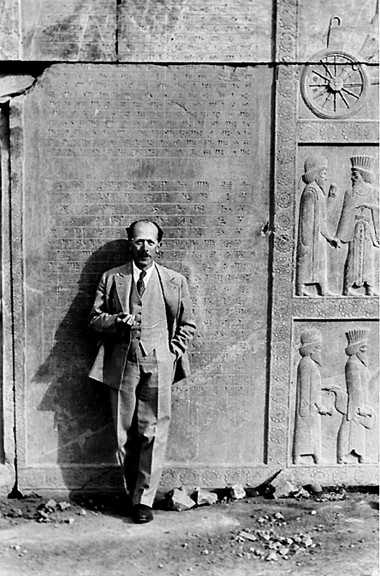

It was the French archaeologist and director of the Iranian Archaeological Service, André Godard who first located the ruins of Persepolis in the early 1930’s. He believed that it was Cyrus the Great, the founder of the Empire, who also founded the city, but however, that it was Darius I who ordered construction to some of its most captivating buildings. Those were the Council Hall, the main imperial Treasury with its surroundings, as well as the Apadana. The construction of the buildings was completed during the reign of his son, Xerxes I.

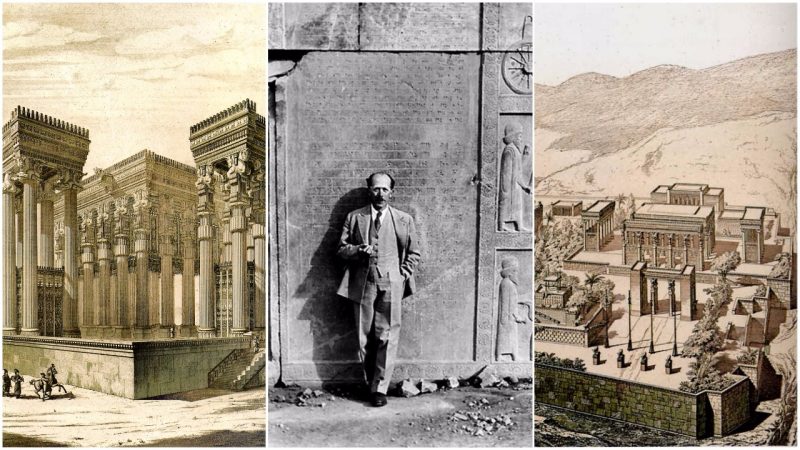

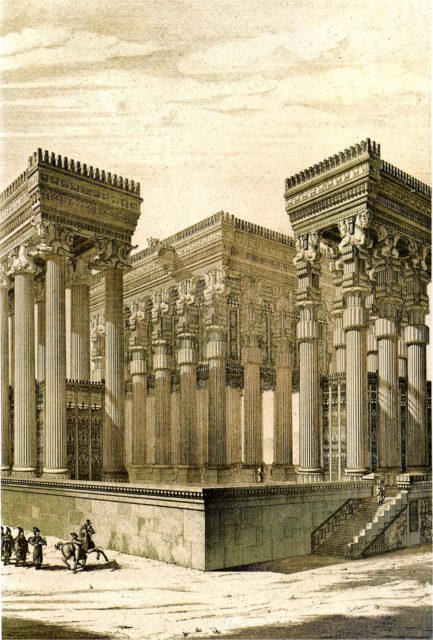

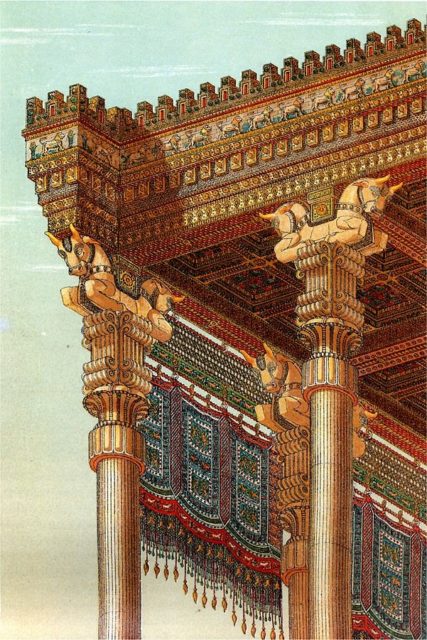

The Apadana was the most authentic building of all; a large hypostyle hall that served as a large audience hall and portico. It was among the first conceived buildings when construction of the ancient city began. In old Persian, the term “a-pad-an” means to be “unprotected” and referred to the actual look of the building.

The hall had a veranda-shaped structure and was opened to the outside world at three of its sides. This distinguished the Apadana from the rest of the palace buildings in Persepolis. Two similar words in Sanskrit also mean “to arrive at” and “a hide out”. The old word survived into later periods in Iran, as well as in a couple of other languages.

The hall was the largest building on the Terrace at Persepolis. It was excavated by the German archaeologist and Iranologist Ernst Herzfeld and his assistant Friedrich Krefter. The site was most likely the main hall of kings, scattered on a surface of almost 1000 square meters. Its roof was supported by 72 columns, each over 20 meters tall, and with complex decors in the shape of bulls and lions.

Two monumental stairways decorated by reliefs gave access to the hall. The reliefs showed the delegates of the 23 nations of the Persian Empire paying tribute to Darius I, who is represented as seated centrally; they are done in extensive detail, portraying the costumes and equipment used by many different people of Persia during the 5th century BC.

Inscriptions on the reliefs read in Old Persian and Elamite, which is an extinct language today. The hall was used for various ceremonies, among which great kings of the empire were paid tribute to from the nations of the Empire, and were given gifts in return. Some modern scholars believe that the nature of the reliefs was also metaphorical, referring to idealized social orders.

The entire hall was pillaged in 331 BC by Alexander the Great’s army. Stones from the columns had been found at nearby settlements, used as materials for other buildings. Only 13 columns were left standing when the site was discovered in the 1930’s. During the 1970’s, one more was added, as it was found fallen but undamaged. That totals to 14 standing columns at the Apadana today.

One more Apadana hall was also built in the ancient city of Susa, but like the one in Persepolis, it has been abandoned after it was pillaged for building materials. The Persian Apadanas may not be the oldest halls of its type in the world.

Here is another story from us: Naqsh-e Rustam: a lasting memory of a once powerful empire

The discovery of hypostyle halls at two Urartian locations had suggested the possibility that the Urartu could have stylistically inspired the Persians. In 1979, UNESCO protected the ruins of Persepolis as a World Heritage Site.