Coastal dwellers in seventeenth century Britain lived in fear of the pirates that roamed the seas. It was common for the people of coastal villages to be kidnapped and sold into slavery in North Africa.

The Corsairs were also busily plundering British shipping whenever they got the opportunity.In the early 1600s, the Barbary Corsairs had permission from their government to attack any Christian ships. Their ships, called xebecs, had great big, oared galleys. They not only took the sailors into slavery but took other ships as well to add to their fleets. Between 1609 and 1616, 466 vessels were captured, according to the British Admiralty records. Another 27 ships were captured near Plymouth in 1625.

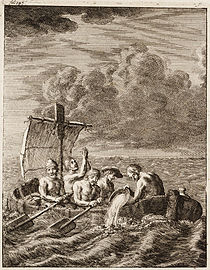

The Corsairs were at the height of their time and clearly ruled the seas. In 1677 the Algerians joined them on the sea and captured 160 British ships. It is estimated that between seven thousand and nine thousand men and women were taken off all of these ships to be sold into slavery.

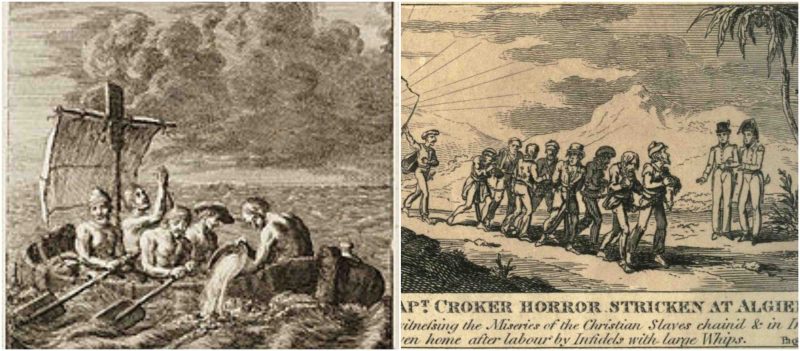

The Corsairs also attacked the coastal villages. They were able to land craft nearby and sneak into the villages at night to grab their victims and get away before any alarms could be sounded. Baltimore, in Ireland, was a small village that lost most of its inhabitants in 1631 in this manner. Known attacks happened in Devon and Cornwall as well.

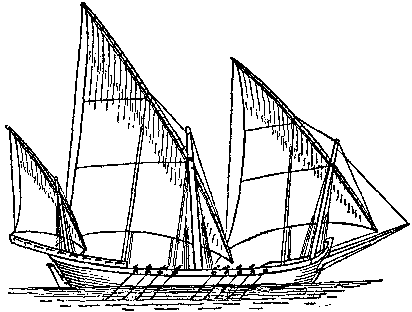

There are accounts, from people who had once been slaves, of the life of a Barbary slave – how they were given nothing but bread and a little water to live on, were regularly beaten on the soles of their feet, and were made to lie all night where they were ordered to go. It was a grim life for a white man to become a slave.

According to records, there were approximately 35,000 European Christian slaves, some in Tripoli and Tunis, with the bulk of them in Algiers. Most of the British slaves were sailors, but the British slaves were outnumbered by the people from the coasts of Valencia, Calabria, Andalusia, and Scilly.

It is thought that approximately nine thousand new slaves were needed a year due to those that died, escaped, or were ransomed. Some slaves even converted to Islam to escape their chains. Most of the slaves taken were poor and thus had little chance of ever regaining their freedom. The officers from the captured ships were the ones most likely to be ransomed by friends and family.

Slaves on the Barbary Coast were generally in two distinct groups – they were either “public slaves” or “private slaves.” The public slaves were the slaves owned by the ruling Pasha who could and did claim an eighth of all captured Christians. A lot of these slaves was hard; they were housed in large prisons that were often overcrowded.

Most of them ended up in the galleys on the oars that rowed the Corsairs in search of loot. Thousands of these slaves died while knowing nothing but the oars for the rest of their enslaved days.

When the seas were too rough and wild in winter, these slaves worked on public projects such as constructing walls, building new galleys, or quarrying stone. They were underfed and had limited water to quench their thirst.

If one collapsed from exhaustion, they were beaten until they rose again and continued to work; otherwise, they died. The Pasha often bought female slaves, and some ended up in his harem and bore him children. Others would have been made domestic slaves of some sort.

The “private slaves” had varied lives depending solely on who had purchased them. Some were very well cared for while, others worked as hard as the public slaves in the fields or construction work. Some would sell water and goods in the markets on behalf of their owners and would be beaten if the coin was not enough. This was a way of encouraging the slave to excel at selling so as to make their owner a nice profit. As with all slaves as they aged or became injured, they were sold away, sometimes many times. As their worth diminished, they were sold further until they died while working or were killed.

Sometimes the Europeans would try to buy some of the people back from slavery. Until 1640 it was a mishmash of attempts, some successful and some not. The clergy were the ones who did the negotiations, and they were often members of the Mercedarian or Trinitarian orders.

Parish churches across Spain and Italy had special locked boxes in their churches just for the fundraising of money for the ransoming of slaves. To be able to ransom anyone became an immense charitable work that gave stature to them and their Parish and the Church as a whole.

However, Britain, Germany, and Holland were rather lax in getting their people free. Britain did set aside some money for the ransoming of slaves, but it was often used elsewhere on more important projects. It was rare for larger-scale ransoms to happen, but in 1646 Edmund Casson raised enough funds to free 244 men, women, and children from the Barbary Coast.

Even though slave numbers dropped due to ransoming, it was mostly the English, Dutch, and German slaves left behind, never to see home again, BBC reported.

The slaves that converted to Islam weren’t freed from anything other than working the oars in the galleys. They still were slaves of the Pasha but went to work elsewhere, such as in the fields and quarries. Sometimes their new lives were just as hard as working the oars.

The slaves in Barbary could be any race or religion. It depended on where and who the Corsairs had been raiding at the time. The fact that the Barbary slavers made no separation of race or religion is a concept so different to the American slave taking, which was about the superiority of one race over another.

Historians are still discovering more about the events and the activities of these highly skilled seamen, the lingering effects of the depopulation of Spain and Italy, and the subsequent effects on city development and the rise in strength of the Catholic Church.