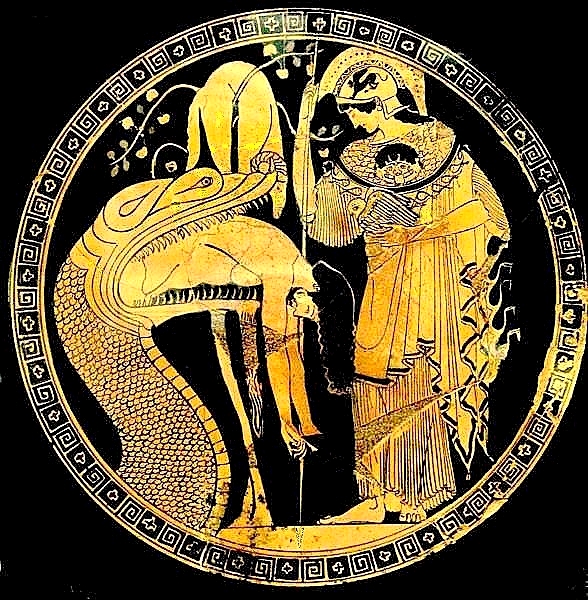

The Gorgons of myth were three sisters, the most famous being Medusa. Her sisters Stheno and Euryale were originally beautiful maidens who were turned into hideous monsters by a jealous Athena.

They were credited with being able to turn a man into stone. Most coins, amulets, and artworks featuring the Gorgon depict just one, which is thought to be a mix of all three women or just Medusa on her own.

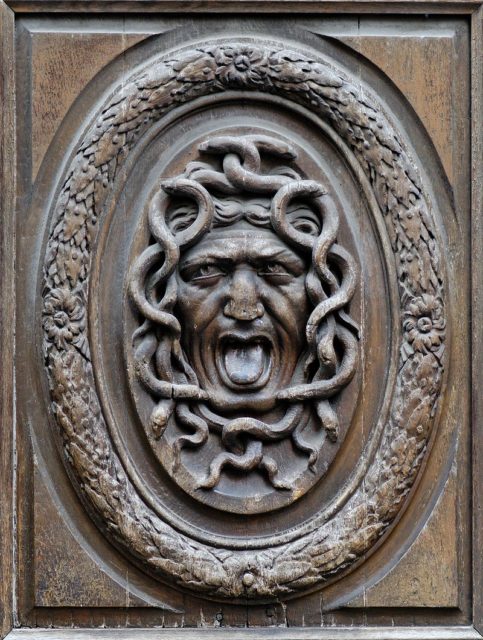

The Gorgoneia (figures depicting a Gorgon head) first appear in Greek art in the eighth century BC. Examples of works with the Gorgon’s face on them were found at Parium and Turyns. The Lithuanian archaeologist Marija Gimbutas believes that the face of the Gorgon appears even further back, to about 6000 BC on a ceramic mask from the Sesklo culture.

In ancient Greece the Gorgon appeared on unique amulets that gave the wearer special protection; it was thought that the Gods themselves, Athena and Zeus, wore these protective amulets.

Homer, the ancient Greek author of the Iliad, refers at least four times to the Gorgon and only describes the head. She is described in early works as very ugly with tusks, a protruding tongue, and eyes that stare at the viewer. This was unusual in Greek art, having the face front-on in that manner. By the time the face of the Gorgon was decorating Greek vases in the fifth century, she was less scary and menacing. The tusks were gone and the snake more stylized than realistic.

Greek temples in the sixth century, in and around Corinth, had Gorgoneia in the form of lion-like masks. In Sicily, Gorgons were found on the pediments of buildings – a good example is the Temple of Apollo in Syracuse. By 500 BC they were not seen as much on monumental buildings but were still seen on the roof attached to the antefixes on smaller buildings.

The image of the Gorgon was not limited to buildings; her image could be found on clothing, weapons, dishes, and coins in the region between Etruria all the way to the Black Sea. The coins were made in 37 cities in all. In coin collections, the Gorgon’s image is second only to those of the major Olympian Gods. Her image can be found on coins in bronze, silver, electrum, and gold. Most of the Gorgon coins found today are struck coin, but some were cast. Her image also appears on Roman coins, usually on the shield, shoulder, or breastplate of the Emperor on the coin. Often the most memorable image of the Gorgon is in mosaic on floors and walls.

They were primarily found near the entrance to guard the house. Her image was also prevalent on kilns in the Attica area near Athens – it is said her image prevented any mishaps.

We have another story for you: Tips for buying sunken treasure coins

The Gorgon was popular not just in Ancient Greece but also in Christian times. It was the most popular in the Byzantine Empire, and later the Italian Renaissance artists revived interest in her scary image. Today she still appears in modern literature.