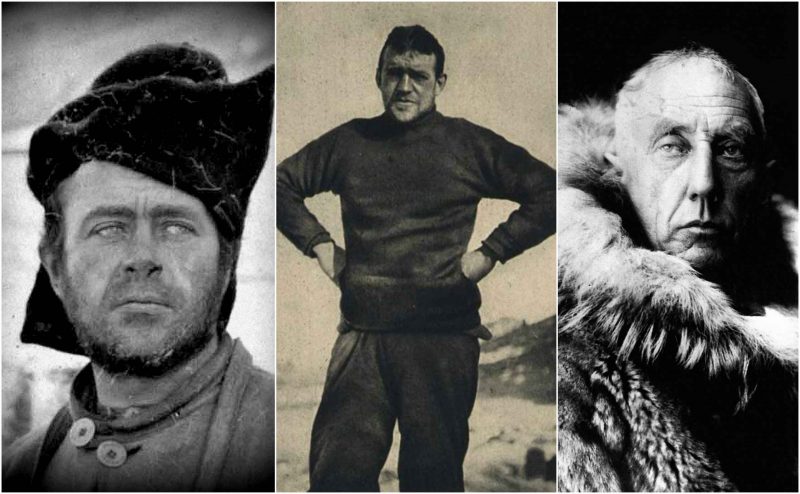

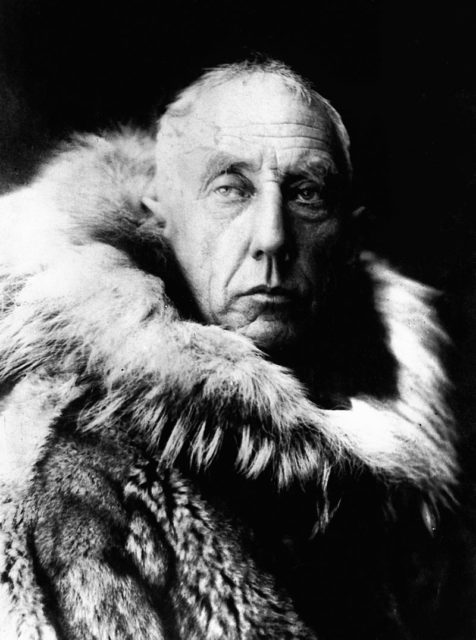

Robert Falcon Scott was a British Royal Navy officer who became a naval cadet when he was only 13. He served on ships all across the world, but he developed a passion for a discovery never made before- a journey to the Antarctic.

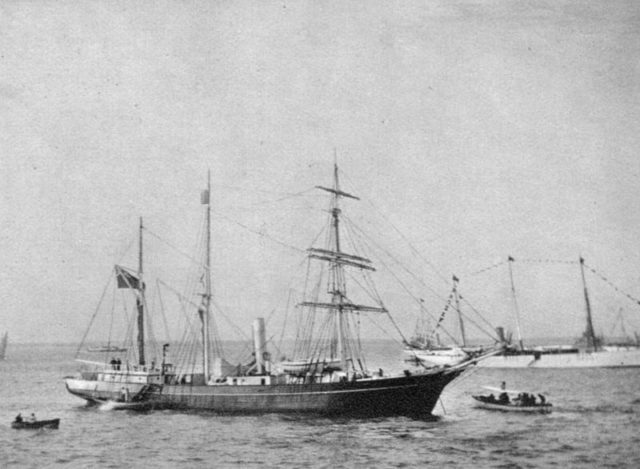

He decided to volunteer for a privately funded, British research mission to the Antarctic, but the RRS Discovery soon fell under the command of the Royal Navy and hence, with his stature and experience, it was easy for Scott to secure the control of the ship.

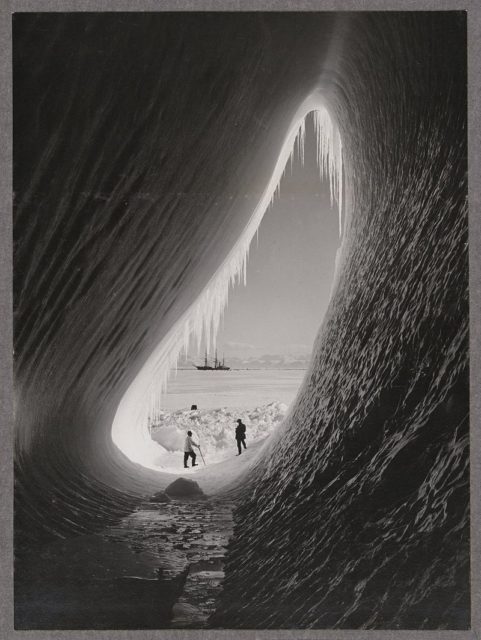

On the 6th August 1901, the RRS Discovery sailed off from the Isle of Wight, and after five months, it reached Antarctica on the 8th January 1902. The expedition on the Antarctic started in summer, so the first few months were suitable for making geographic, zoological, and scientific observations, as well as collecting examples. When the winter came, Scott decided to begin with his mission and anchored up at McMurdo Sound. One thing was the two-years-long scientific observation of the continent, while his main aim was to reach the South Pole.

Scott headed to the South Pole accompanied with his third in command offer – Ernest Shackleton and the zoologist Edward Wilson. On 2nd November 1902, along with their dogs, the three men left the RRS Discovery. Unfortunately, the party lacked experience with sled dogs, plus the dogs’ food had gone bad very soon after they left.

So, on 31st December 1902, when they were at a latitude of 82°17’S which was the most southern point anyone had ever reached until that moment, the three men were forced to turn back.

They were already exhausted, and on their way back to the camp, Shackelton suffered from scurvy and was tortured by the pain. He had to be supported by Wilson because he couldn’t walk on his own. After a month, on the 3rd February 1903, the party reached RRS Discovery.

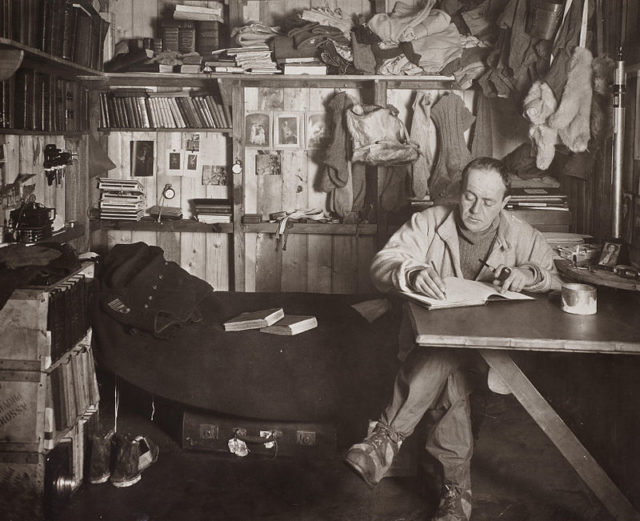

Shackleton was immediately sent back to England on the relief ship to recover while the RRS Discovery remained for another year in Antartica for scientific research and returned to the UK on 10th September 1904. When Scott returned to London, he got promoted to Captain and got a leave from the Navy so that he would have the time to write the official expedition account.

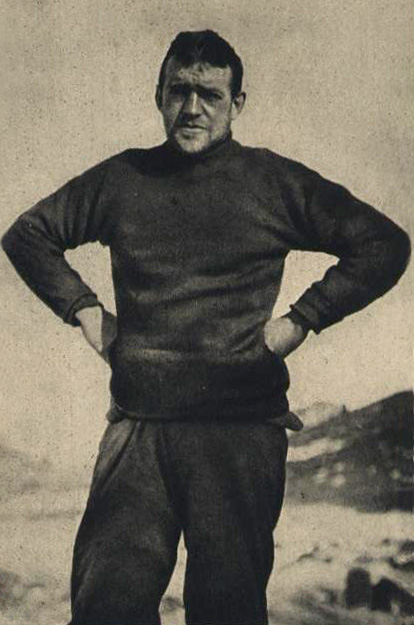

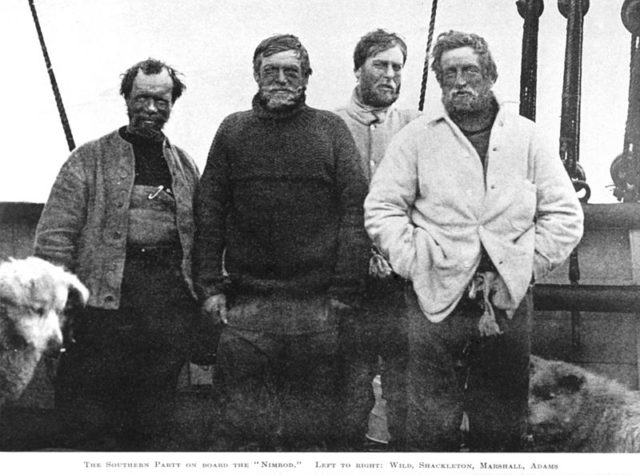

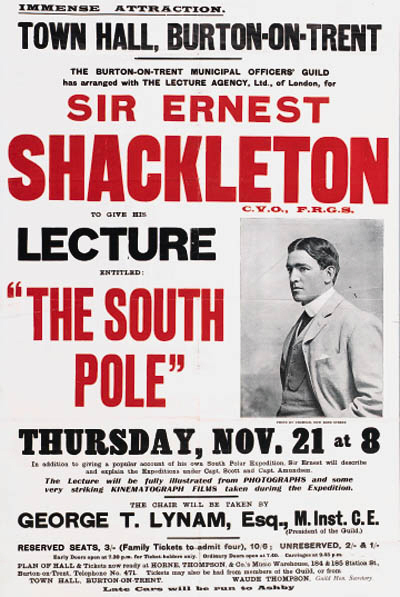

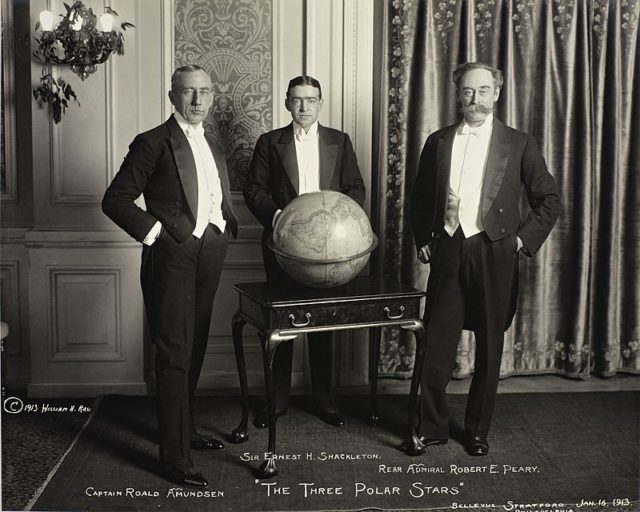

In 1905 the expedition report was published as a book in which Scott has stated Shackleton’s illness as the main reason for the party’s failure to reach the South Pole. This statement led to hostility between the two men. Scott was a well-established figure in the elite British society, and his claims were respected. However, Shackelton was still willing to prove himself so in 1907 and securing enough funding, he led the second British expedition to the Antarctica and named it the Nimrod Expedition.

Shackelton originally planned to base his Nimrod Expedition at the old base on McMurdo Sound but received a letter from Scott saying: “…I am sure you will agree with me on this, and I am equally sure that only your entire ignorance of my plan could have made you settle on the Discovery route without a word to me”.

Shackelton decided to base his camp on King Edward VII Land, but when he reached Antarctica on 23rd January 1908, he realized that the Ross Ice Shelf had changed since the last time he was there. He was left with two choices – to forget the mission and return or to base at McMurdo Sound.

He decided to go forward with his expedition. When he reached the Sound, Shackelton was unable to navigate through the pack ice, and instead of anchoring at the old Discovery camp, he set up a new camp 23 miles north at the new “Cape Royds” base.

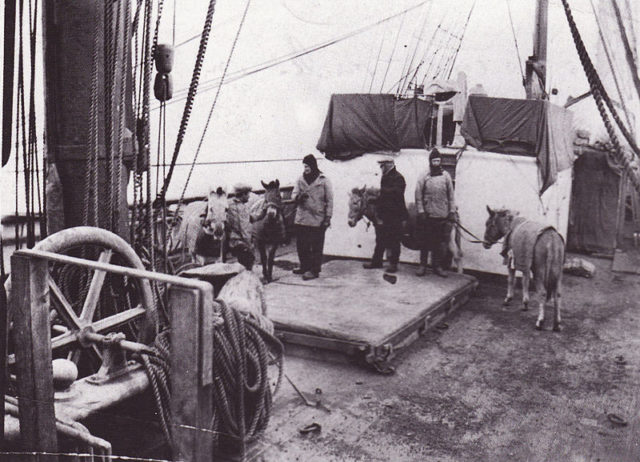

During the summer, the expedition managed to complete some of their secondary plans, and when the winter came, Shackleton was preparing to reach the South Magnetic Pole. He led the party that started the journey on 29th October 1908 and used ponies for transportation of their supplies, but the animals couldn’t endure the harsh weather, and all of them died in less than a month.

The weather wasn’t on their side, and quite often they couldn’t leave their tents because of blizzards and winds. Soon they ran low on rations, and by 9th January 1909, only 97 miles away from the pole, they had to choose if they are going to have glorious deaths or return home alive. They turned back to the Nimrod at a point of 88°23’S.

While Shackelton was away, Scott was preparing for his second expedition to the Antarctica which he named Terra Nova Expedition. He sailed off on 4th January with a crew of 65 men. When they arrived in Australia, Scott learned the news that the Norwegian explorer, Roald Amundsen, headed to discover the South Pole.

Hence, the race started. Scott and his crew worked fast. As soon as they arrived in Antarctica, they began exploring the area and got to Amundsen’s base. However, the Norwegian explorer and his people weren’t very welcoming and happy to greet them.

Scott was outraged and at first wanted to confront Amundsen but then concentrated on planning the journey to the South Pole. It wasn’t only the weather that he was supposed to deal with, but also the time. His plan was fifteen people, divided into three groups to join him on the journey.

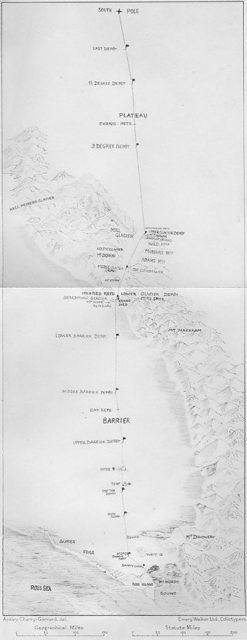

The groups would meet regularly and support each other until the end when Scott would decide upon the fittest and the most prepared to make the final efforts with him. On 24th October 1911, the first group, called “Motor Party” left Cape Evanson.

On 1st November the other two groups set off and met with the Motor Party after three weeks. As they were approaching the end of the Ross Ice Shelf, on the 4th December they were struck by a blizzard and couldn’t move out of their tents for five days.

Their progress was slow, their supplies diminishing, and their horses exposed to the weather outside the tents. When the blizzard ended, the team killed the horses for food. Even though Scott had sent seven of his men back to the base so that they would bring dogs, his orders were either forgotten or not taken seriously.

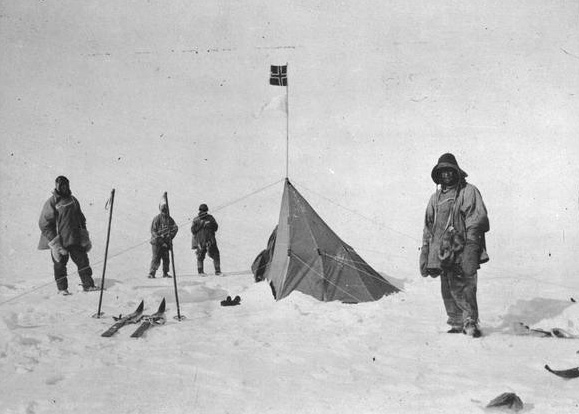

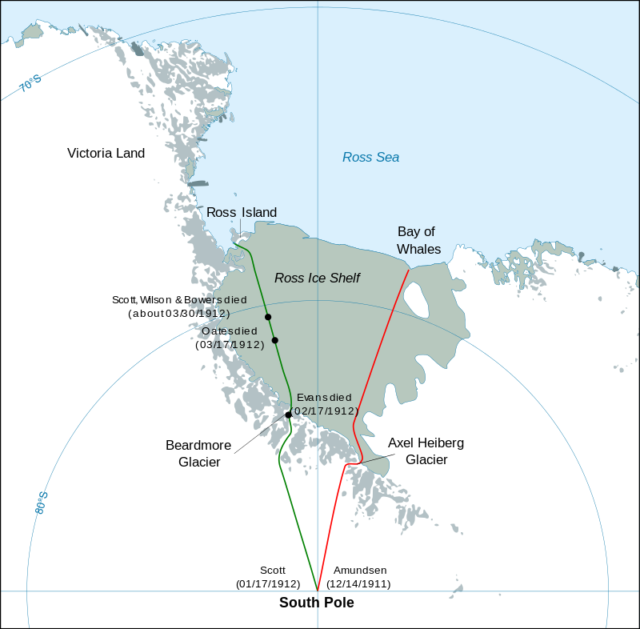

Scott reached Shackleton’s further point south on 9th January 1912 and continued further. Weakened and exhausted, the group sighted the South Pole on 16th January.

They arrived at this “sighting” on the 17th January only to discover the Norwegian flag set there by Amundsen, who had reached the spot a month before them. As Scott famously wrote: “The Pole. Yes, but under very different circumstances from those expected”.

The next day, the group of five people begun their journey back to Cape Evans. It was an 883-mile long journey of which the first half was relatively smooth. But as they hit the Beardmore Glacier they weren’t able to move because of the weather. The men were suffering from exhaustion, malnutrition, and frostbite.

On 17th February, Edgar Evans was the first to collapse. He died the same day, and the rest of the team continued their way. When they were on the Ross Ice Shelf, they were struck by the worst weather ever recorded in the area. They couldn’t make a move for days.

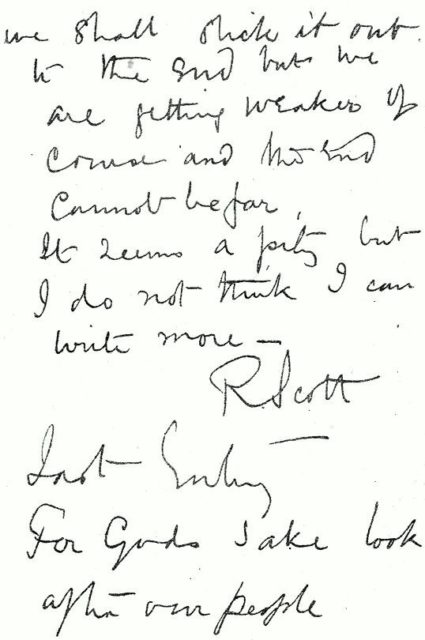

On the 15th March, Lawrence Oates couldn’t carry on and begged Scott to leave him in his sleeping bag. As Scott refused, one evening Oates just left the tent and was never seen again. All this is known from Scott’s diary. The last entry in it was made on 29th March when the group was only 11 miles away from a depot where they could get the supplies they needed.

Scott ended his last entry saying: “It seems a pity, but I do not think I can write more.” He died soon after, and his body, as well the others with him, were found on 12th November by a search party.

The bodies of Scott, Wilson, Bowers, Oates and Evans still lie within the ice of Antarctica.