UMass Boston’s Andrea Fiske Memorial Center for Archaeological Research has been running an archaeological field school for the past few years. David Landon, the associate director of the Center, offers this opportunity to undergraduate and graduate students to take part in an active excavation.

Landon’s original goal had been to find evidence of the original Plymouth Colony well before its 400th anniversary in 2020. He had been awarded a three-year grant for this, and he managed, with the help of his students, to find evidence in the first year of his dig.

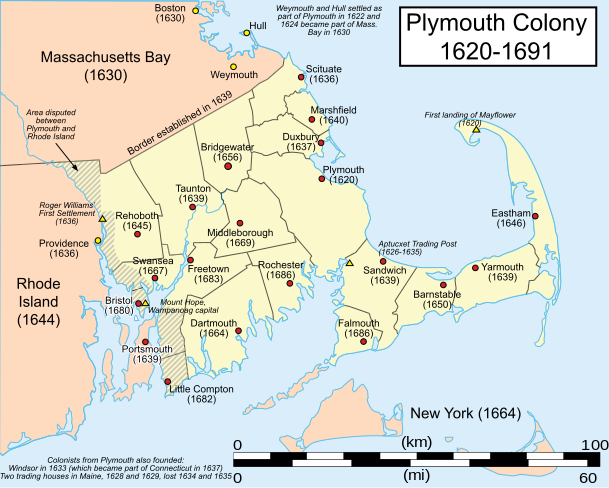

Plymouth was settled in late December of 1620 by approximately 100 men and women. About 40 of these were members of the English Separatist Church (Puritans), and they were looking to make a new life in the New World. They sailed on the Mayflower, a merchant ship, and they landed on the shores of what is now Cape Cod in Massachusetts. The first winter was harsh and over half of the settlers died. The survivors were able to create a peace treaty with their Native American neighbors, and the settlement became nearly self-sufficient in only five years. The harvest feast that the Pilgrims shared with the Pokanokets (one of the local tribes) is what today’s Thanksgiving Day feast commemorates.

The site the team was excavating is called Burial Hill; it is a historic site that was used as a cemetery, and its grounds are known to contain the remains of some of the original settlers from the Mayflower. The excavation took place in the sandy soil at the base of the hill.

The team wasn’t looking for bricks, as it was thought that the structures built at this time were made of wood. Wood can deteriorate rapidly over time, and so the team had to search the sandy soil for posts and ground constructions. Archaeological digs are painstakingly slow, as every centimeter excavated needs to be examined and the team needs to see if any patterns are forming and make interpretations about what can be seen. According to Landon, it’s not so much about finding artifacts but identifying when the soil color changes and why it’s doing that.

They did find post and ground construction in their dig as well as artifacts from the 17th century. Some of the items that were uncovered included trade beads, pottery, musket balls, and tins. From this, they were hopeful they were inside a settled area. The next major find was at the bottom of one of the archaeological pits: the remains of a calf.

Domesticating cattle in the 17th century was a European activity, and so the team can assume the calf they named “Constance” lived and died in the early Plymouth settlement. Cattle in early settlements were very important and were directly connected to the success of a colony, Science News Journal reported.

The curator of collections at Plimoth Planation, Kathryn Ness, is hoping that the finds that Landon and his team of students have discovered could be used to further understanding of how early European settlements developed in New England. This is the first proof ever found of the settlement’s location and the items were available to the Pilgrims.

The artifacts and information gathered by Landon’s team will inform the exhibitions at the Plimoth Plantation, as they want to keep their information as accurate as possible. Archaeologists are busy with the finds, cleaning and researching them. They are also closely looking at the calf to see if they can determine why it was buried and not eaten. Another dig will commence next summer and perhaps provide further answers to historians’ questions.