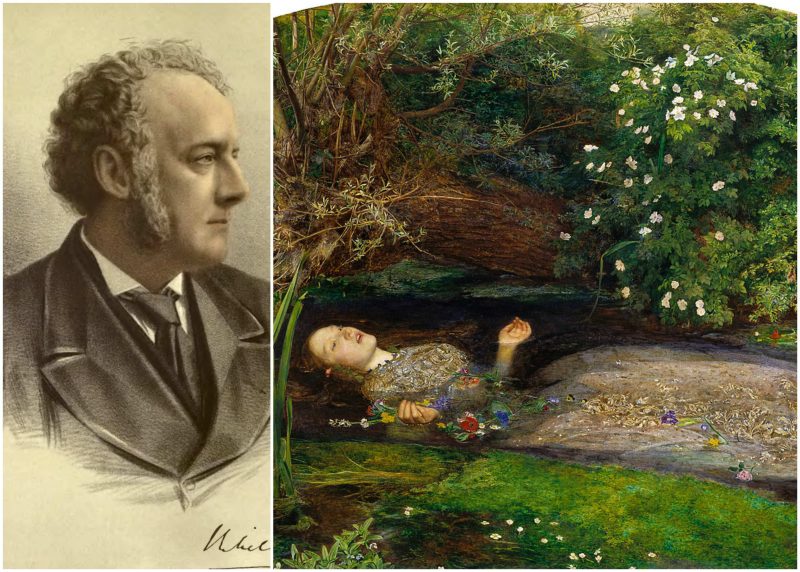

Ophelia is a painting by the Pre-Raphaelite artist Sir John Everett Millais. The British painter was inspired by Shakespeare’s Hamlet, and it perfectly captures the mystical atmosphere when Ophelia sinks to her death in a Danish river.

It was painstakingly completed between 1851 and 1852 and is regarded as one of the most important works of art to emerge from the Pre-Raphaelite movement.

1. It was sold for 300 guineas, the equivalent of around 320 pounds

An art dealer, Henry Farrer, originally bought Ophelia for 300 guineas. The painting was later sold on again and again, with its price constantly going up.

At its premiere exhibition, it was not critically acclaimed and was overlooked. Today, the work of art is worth a staggering £30 million.

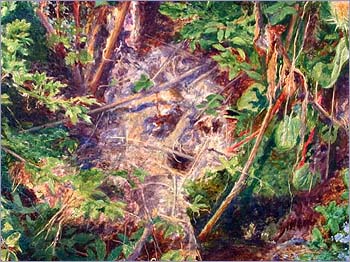

2. Millais worked outdoors, on the banks of the Hogsmill River in Surrey

Millais took the artistic endeavor very seriously. He worked for 11 hours a day throughout five months in 1851, in hopes of capturing the very essence of the drowned Ophelia. He thought that the picturesque landscape of the Hogsmill River would prove a perfect surrounding for painting his magnum opus.

But, it was no easy task, as he was in a constant fight against the elements.

In a letter, the frustrated artist complained to a friend: “The flies of Surrey are more muscular, and have a still greater propensity for probing human flesh. I am threatened with a notice to appear before a magistrate for trespassing in a field and destroying the hay … and am also in danger of being blown by the wind into the water. Certainly, the painting of a picture under such circumstances would be greater punishment to a murderer than hanging.” According to the research of Barbara Webb, the exact location where the painting was made is at Six Acre Meadow, alongside Church Road, Old Malden.

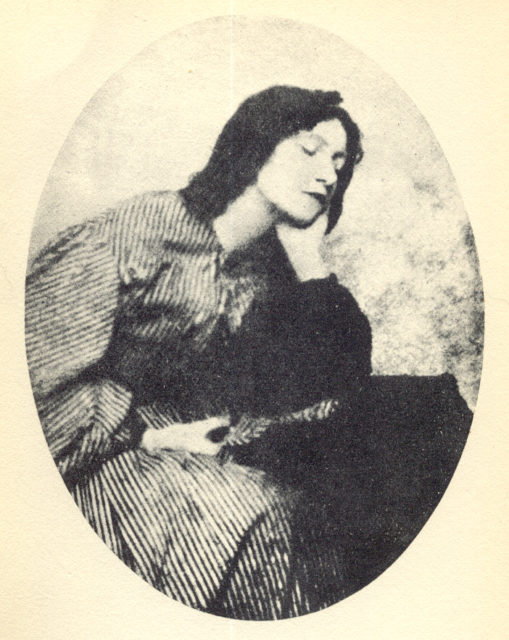

3. Ophelia was modeled after Elizabeth Siddal, who caught a cold while lying in the water

Millais knew there was absolutely no way to persuade someone to lie still for hours in the cold, dirty waters of Hogsmill. He came up with a much less demanding approach.

There was a 19-year-old girl who went by the name of Elizabeth Siddal, whom Millais persuaded to lie still, fully clothed, face up in a bathtub.

The determined painter believed that relying simply on raw imagination for painting Ophelia would be very foolish, so Siddal was the perfect model for the job. Oil lamps were placed under the bathtub to keep the water warm but to no avail. Siddal quickly caught a cold, and Millais got himself a £50 doctor’s bill.

4. Salvador Dalí was a huge fan of the painting

In the 20th century, the eccentric surrealist championed the painting. In 1936, the surrealist wrote: “How could Salvador Dalí fail to be dazzled by the flagrant surrealism of English Pre-Raphaelitism?

The Pre-Raphaelite painters bring us radiant women who are, at the same time, the most desirable and most frightening that exist.”

5. It received harsh criticism by the time of its public debut

Many critics were not impressed by Ophelia’s charms. During the time of its first exhibit at the Royal Academy in London in 1852, many newspapers criticized Ophelia’s “perverse” impression and the choice of background setting.

An art critic for The Times wrote that “there must be something strangely perverse in an imagination which houses Ophelia in a weedy ditch, and robs the drowning struggle of that lovelorn maiden of all pathos and beauty”. Another review in the same newspaper criticized the painting: “Mr. Millais’s Ophelia in her pool… makes us think of a dairymaid in a frolic”.

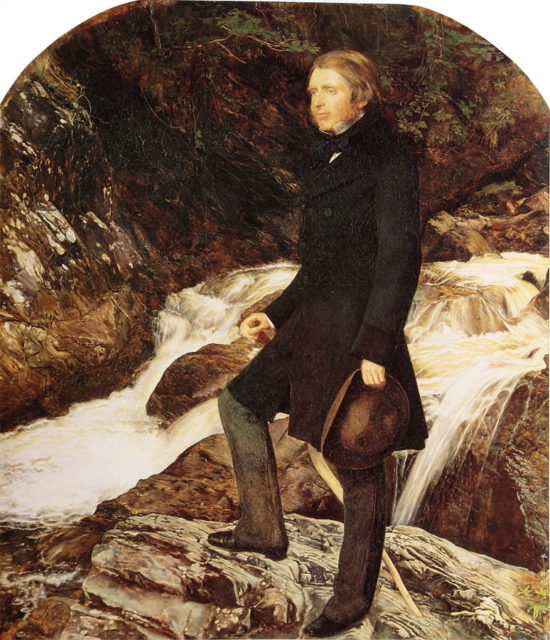

Even the prominent art critic John Ruskin, who was an avid supporter of Millais’ work, wrote that even though he found the technique of the painting “exquisite”, a water-soaked Surrey landscape didn’t quite meet his expectations: “Why the mischief should you not paint pure nature, and not that rascally wirefenced garden-rolled-nursery-maid’s paradise?”

6. There was once an unknown critter hidden in the bushes of the painting

Millais considered adding an animal on the side of the painting, in hopes of esthetically incorporating a spontaneous landscape. During the early process of the painting, Millais drew a water vole swimming alongside Ophelia.

He showed the unfinished animal to William Holman Hunt’s relatives in December 1851, writing a journal in his diary: “Hunt’s uncle and aunt came, both of whom understood most gratifyingly every object except my water rat.

The male relation, when invited to guess at it, eagerly pronounced it to be a hare.” Much to the painter’s dismay, he had failed to precisely portray a recognizable animal.

“Perceiving by our smiles that he had made a mistake, a rabbit was next hazarded. After which I have a faint recollection of a dog or a cat being mentioned”. The alleged raccoon-dog-cat-rabbit didn’t live to see the light of day when the painting was unveiled at the Royal Academy exhibition in 1852. It is believed that Millais drew a prototype sketch of the unknown creature in the upper corner of the canvas, which is now obscured by the frame.

7. Millais’ studio where he worked on Ophelia still exists

Surprisingly, the 200-year-old building still stands tall in London. Its location is at 7 Gower Street, on the second floor, to be precise. A blue plaque can be seen on the building: “The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was founded here in 1848”. The building now serves as an office for an oil and gas company, and the bathtub where Siddal posed has been replaced by a photocopier.

8. Ophelia may be the most characteristic work of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood’s distinctive style

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood’s most distinguishable artistic object was, undoubtedly, “the vulnerable woman”, with Ophelia standing as a perfect example. She is portrayed as a young, hopeful woman, who is met with the tragic undertone of inevitable death looming over her.

Millais flawlessly utilizes the intense, vibrant colors of her dress and the detailed background flora, to contrast Ophelia’s pale face with the surrounding. The artist succeeds in emphasizing the growth patterns and natural fade of the flora and the ecosystem.

9. Ophelia is a big deal in Japan

A Japanese novelist, Nasume Soseki, is responsible for spreading the word about Ophelia in his home country. The painting was popularized almost to the point of receiving a cult following. In one of his novels, the famed novelist mentioned the painting as “a thing of considerable beauty”.

During a Millais exhibition in Tokyo in 2008, the Japanese decided not to use the painting on promotional posters. The reason for the strange decision was simply because of Japan’s suicide culture which was growing at an alarming rate. They thought that the painting would romanticize death, targeting young Japanese women who would take their own lives for love.

10. Many of today’s pop culture tributes pay respects to Millais’ Ophelia

Ophelia today is an often mentioned pop culture subject, from being used as an album cover for black metal bands, to witty references and homages in animated comedy shows. One of the most popular homages to Ophelia can be seen in Nick Cave and Kylie Minogue’s music video for the ballad “Where The Wild Roses Grow”, portraying the singer drowning in a river.

Even though the brilliant work was not critically acclaimed when it was first exhibited at the Royal Academy, it has since grown to be regarded as a very important piece of art. Ophelia has been in the Tate Museum in London for almost 117 years and has attracted many viewers to admire its mystical detail. The souvenir postcard of Ophelia in the museum is still a hit shopping item among tourists and visitors.