It was 1929 when George Remi, best known under his pen name Hergé, started working as an illustrator in quite a conservative Catholic newspaper known as the Le Vingtième Siècle (The Twentieth Century) in Brussels.

The newspaper, though active since 1895, sold poorly but was kept alive by Belgian aristocrats and politicians who supported its ideology. Hergé worked under Abbé Norbert Wallez, a priest and journalist who described the paper as a “Catholic Newspaper for Doctrine and Information”. Most of the issues had a far-right and even fascist viewpoint. Wallez appointed the young cartoonist, only 22 at that time, to edit the Thursday youth supplement of the newspaper, Le Petit Vingtième (“The Little Twentieth“). Aside from editing, Hergé also illustrated a comic strip that was authored by another member of the newspaper, however, he was not so pleased with the work and demanded to write and draw his own comic.

Hergé already had some experience in creating comics. At around the age of 19, he had created one about a boy scout patrol leader that was released in a scouting newspaper, titled “The Adventures of Totor, Scout Leader of Cockchafers”. The character of Totor from his first comic would strongly influence Hergé’s most famous character, known to comic lovers as Tintin. The cartoonist would remark that Tintin was like Totor’s younger brother.

The first volume about the encounters of Tintin was published in “The Little Twentieth” and that marked the beginning of a new era in the world of comics. Little did Hergé know at the time that this was to become one of the world’s most famous and successful comics, selling out over 200 million copies worldwide. But wait until you hear the whereabouts of the first (and the second) volumes…

Tintin in the Land of the Soviets

Although Hergé got to work on a comic strip of his own, it was Wallez who ordered the setting for Tintin’s story. The cartoonist wanted to set the first volume in the United States, where the young Belgian reporter and adventurer Tintin, followed everywhere by his faithful dog Snowy, meets the Native Americans, (since childhood Hergé had been largely fascinated by them). The editor, however, rejected the idea and made him set a story in the Soviet Union.

The story had to bring about a sentiment of anti-socialist propaganda for children. The Soviet government, being atheists, anti-Christian, and extreme-left in nature, was everything Wallez despised. Tintin’s first adventure needed to reflect exactly that, indoctrinating its young readers with anti-Marxist and anti-communist ideas.

The volume was done, published as Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, and serialized in “The Little Twentieth” from January 1929 to May 1930. As Wallez was popular in Francophone Belgium, he went on to organize a publicity stunt, following the publication of the story in book format. Soon enough, the comic became popular and it increased the sales of the newspaper. The adventures of Tintin really began under a veil of political propaganda.

When Hergé was later asked to explain why he had produced a work of propaganda, he said he had been “inspired by the atmosphere of the paper”, where being a Catholic had meant being anti-Marxist.

The controversies of the second volume

At Wallez’s direction, Hergé proceeded to work on the second Tintin story, which follows the character through his encounters in the Belgian Congo. For this issue, the cartoonist, in later decades, was accused of racism.

The volume was done in a sort of paternalistic style that depicted the Congolese as childlike idiots. The sentiment is announced at the very beginning of the story when Tintin and Snowy are greeted by a cheering crowd of natives upon their arrival in the heart of Africa.

In a talk with the French writer, actor, and director, Numa Sadoul, the Belgian cartoonist defended himself, “For the Congo as with Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, the fact was that I was fed the prejudices of the bourgeois society in which I moved … It was 1930. I only knew things about these countries that people said at the time, ‘Africans were great big children … Thank goodness for them that we were there!’ Etc. And I portrayed these Africans according to such criteria, in the purely paternalistic spirit which existed then in Belgium”.

For the third adventure, Tintin finally did make it to America. As Hergé was allowed to pick the story on his own this time, the volume still kept to the agendas of the newspaper under which it was published, but better times were just around the corner.

The Adventures of Tintin evolved into a lifetime adventure for Hergé. The cartoonist would note, “The idea for the character of Tintin and the sort of adventures that would befall him came to me, I believe, in five minutes, the moment I first made a sketch of the figure of this hero: that is to say, he had not haunted my youth nor even my dreams. Although, it’s possible that as a child I imagined myself in the role of a sort of Tintin”.

The times of Tintin changed once new volumes were published in Belgium’s leading newspaper Le Soir, and spun into a successful Tintin magazine. After the war, Hergé also opened his own studio which started to produce canonical versions of the story. The comic was subsequently adapted for radio, television, theater, and film.

The main character nurtured the imagination of its readers with his voyages to faraway countries such as Egypt, India, and China. Tintin was also sent to fictional countries that Hergé invented; the Latin American republic of San Theodoros was a banana republic under the yoke of a military government; the East European kingdom of Syldavia was situated in the Balkans and had a rivalry with the neighboring fascist state of Borduria, whose leader Müsstler, was a combination of Hitler and Mussolini.

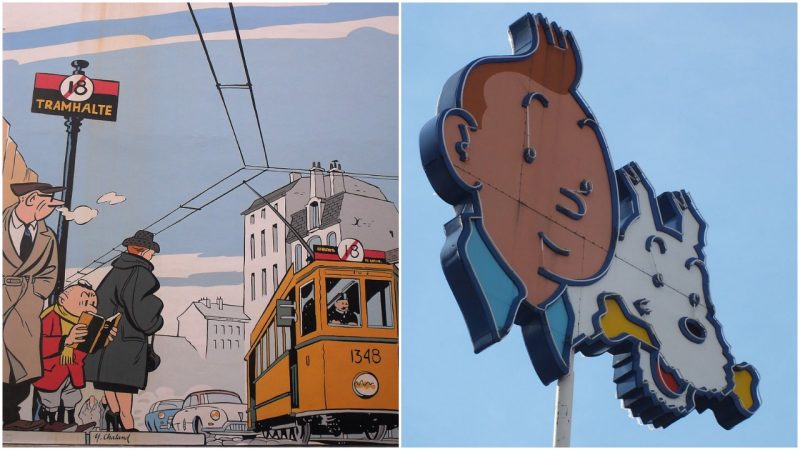

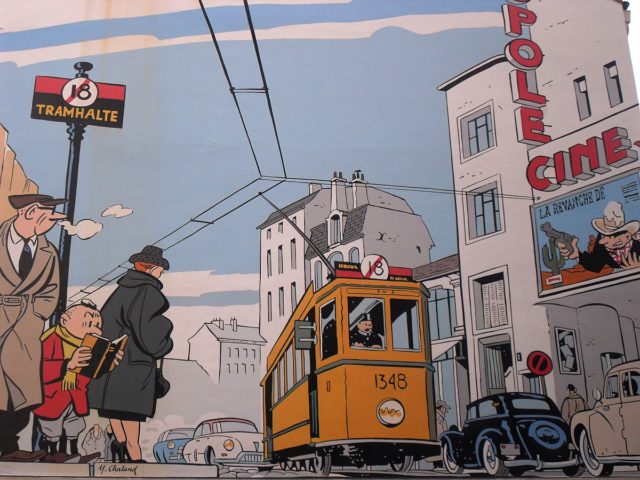

With his work, Hergé pioneered the “ligne claire” (clear line) drawing style, emblematic for the usage of strong lines all of the same width without hatching, while contrast is downplayed. The imaginary world of the young Belgian explorer captivated audiences worldwide with its slapstick humor, satire and regular political and cultural commentary.

With 24 volumes of The adventures of Tintin released in total, Hergé had placed Belgium as a leader in comic book production.

Here is another story from us: A best-selling book from 1919 was written by a 9-year old

And remember, it all started in a pro-fascist newspaper, with a first edition that nurtured nothing but Soviet propaganda.