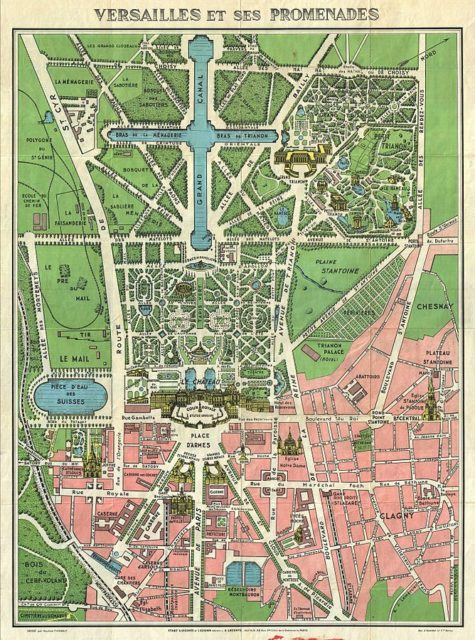

The Palace of Versailles once housed the French government, or more accurately speaking – the French royal family. It was the permanent royal residence during the reigns of Louis XIV, the French popular “Sun King”, and also Louis XV and Louis XVI, and continued to be so until the French Revolution in 1789.

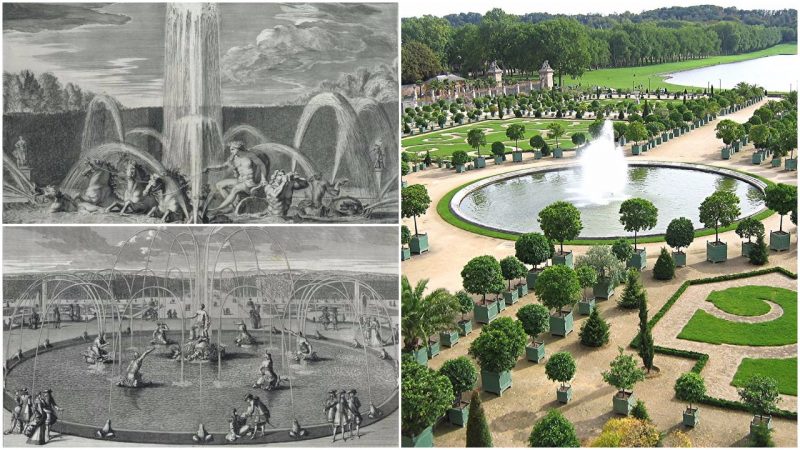

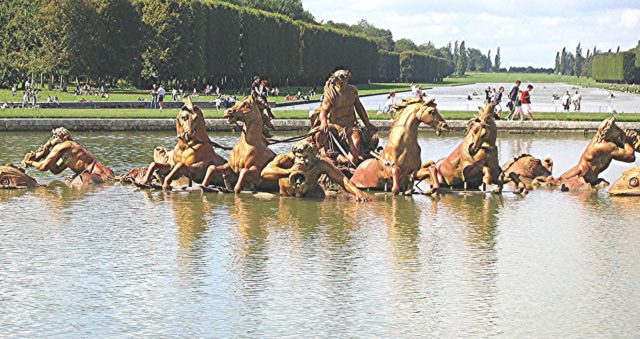

The complex of Versailles never ceased to be one of the marvels of France. Its spacious gardens, scattered over 800 hectares of land, for centuries, remained a captivating sight for the human eye. Still, the beauty of the place came with a cost, and in the case of the gardens, it was providing water for its numerous fountains.

The water challenge appeared as soon as Louis XIV began to expand the gardens with more and more fountains. At the start of the expansion project, water was pumped to the gardens from ponds near the château. A big proportion of the water required was pumped to a reservoir on the site which transported water to the fountains through gravitational hydraulics. By 1664, the water demand only increased, when a water tower was erected north of the château. It drew water from a pond named Clagny, the largest resource of all, and its capacity was 600m3 of water per day.

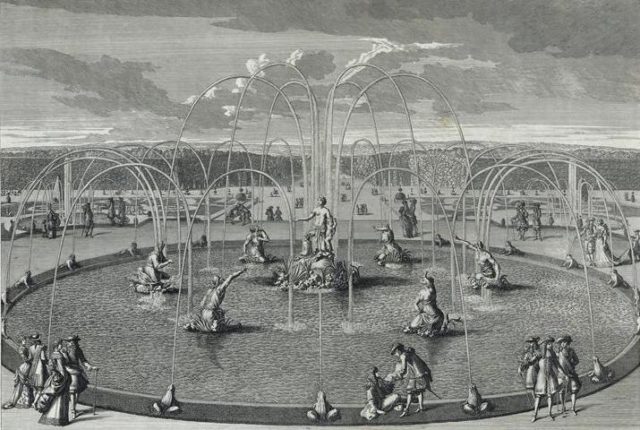

By 1671, these much-appraised gardens had their own Grand Channel system that served as drainage for the fountains, using the force of several windmills. Despite the new system largely resolving the supply problem, there was still never enough water to keep all the fountains going in the garden all of the time. That was simply impossible, and so normally, only the fountains seen directly from the palace were left running all of the time.

The following year, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, the French Minister of Finances and notable politician of that period, came up with a system by which the people who maintained the fountains would signal each other with whistles upon the approach of the king. The whistle was a sign that if a fountain was off in that moment, it needed to be turned on. Once Louis XIV had passed that particular operating fountain, that fountain would go off and a whistle would be blown from there to signal for the next one to be turned on.

By 1674, the capacity of the pump that drew water from the Clagny pond increased and it was able to pump nearly 3,000 m3 of water per day. The pond was sometimes left waterless. Whatever was done, it was just not enough. The gardens always needed more and more water.

Between 1668 and 1674, another project was started, and it aimed at diverting water from the nearby Bièvre river to Versailles. This system had the capacity to supply an additional 72,000 m3 of water to the gardens. The numbers already look crazy, right? Just wait until you read about the next big project!

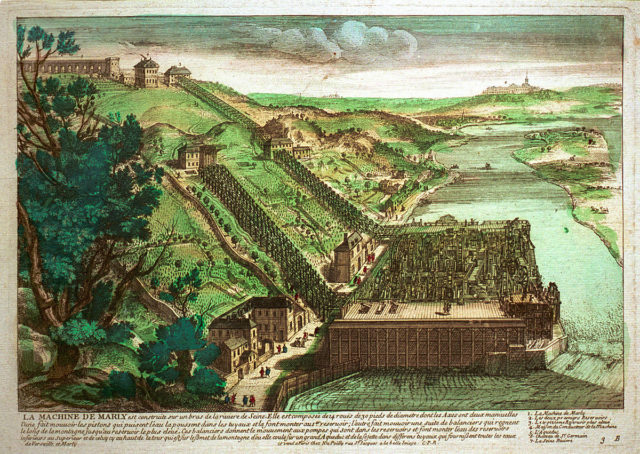

The most ambitious projects of all followed in 1681. As the Seine river was close to Versailles, a construction plan was proposed to raise the water from the river and deliver it to the extravagant complex.

The project began and a huge hydraulic system was installed in Yvelines. It was completed by 1684, and it pumped water from the famous river to supply the royal residence. It was called Machine de Marly.

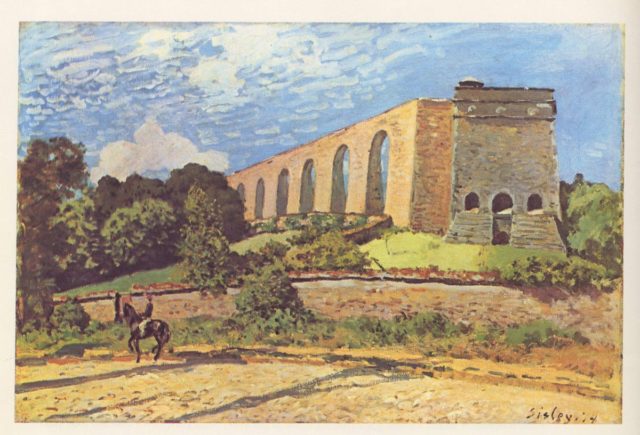

The construction effort was designed to lift water from the Seine in three stages to the Marly Aqueduct, which was some 100 meters above the level of the river. Enormous waterwheels constructed in the river raised water with the help of 64 pumps. The water was first distributed to a reservoir set 48 meters above the Seine. From there, with the effort of another 79 pumps, the water went an additional 56 meters up to a second reservoir. 78 more pumps transferred the water finally to the aqueduct which carried it to Versailles, as well as to Marly, a second smaller royal residence nearby.

Despite the Marly Machine being run on full power, it failed to fulfill expectations. Frequent leakage and collapse in the complex mechanism oftentimes slowed down the work, and the system was able to deliver only 3,200m3 of water per day.

It’s a pity indeed, as the original intention was to double that number. By this point, the costs for the water supply system made one-third of the full costs to run Versailles. The fountains were still limited to operate at half-pressure, consuming 12,800 m3 of water per day, which was more water per day than the entire city of Paris would spend. The Marly Machine kept on operating until 1817.

One last attempt to resolve the water deficit problem took place in 1685 when up to 10,000 troops were forced to work on a new construction project which required diverting water from the Eure river.

Unlike other water resources, this river is situated 160 kilometers away from Versailles. During the second year of its construction, 20,000 soldiers were deployed to the field, to work on a new channel and aqueduct constructions.

This project was never completed as the War of the League of Augsburg would begin during that period. If the construction would have been finished, Versailles would have had an estimated 50,000 m3 of water per day.

That would have been more than enough to resolve the water issues once and for all. Even today, despite modern technology, water still continues to be an issue at the complex. Undoubtedly, beauty comes with a price.