The ancient Roman object in a shape of a pork leg was excavated from the Roman town of Herculaneum in the 1760s.

The town was destroyed by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD. The city was preserved by a thick layer of tufaceous material (soft, porous, and friable sedimentary rock) of 15-18 meters in depth. This layer was a real challenge for the excavation, but on the other hand, it prevented looting and tampering with the site. The excavations at the site began in the 18th century, though at that stage no one was aware of the existence of the city.

It was found by accident when a well was being dug in 1709 and drillers discovered a wall that was part of a theater stage. Treasure hunters dug up and took some artifacts. The King of Naples supported excavations, and a military engineer by the name of Karl Weber directed the dig and created diagrams and maps of the site.

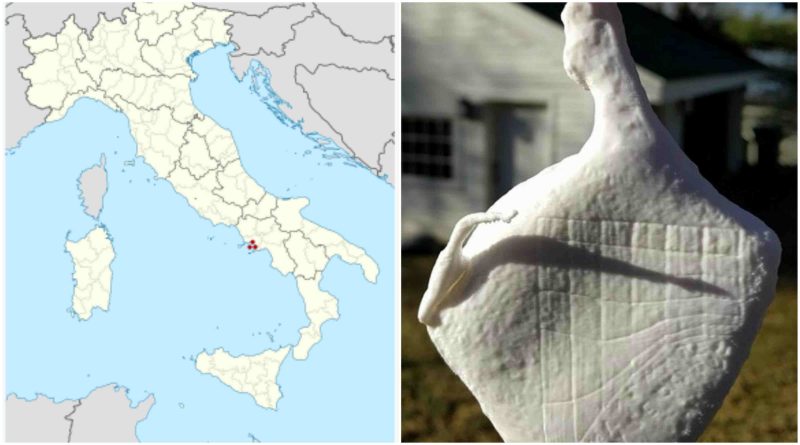

The latest artifact is a small piece of metal, rather amusingly shaped like a ham and known as the world’s earliest sundial. Christopher Parslow from Wesleyan University made a 3D copy of the sundial to help him figure out what the object was.

He says that it can be used to tell the time and shows that the ancient Romans understood how the sun moved across the sky. The sundial was removed from the ruins of the Villa Dei Papiri, which used to be a country house. It is evident that early scholars had realized that it was a sundial. Only 25 ancient portable sundials were found, Mail Online reported.

Parslow’s 3D-printed sundial, like the original, has a grid on one side. The vertical lines are the months and the horizontal the hours before sunset or past sunrise. The original artifact is missing the gnomon, which is the part of a sundial that casts light.

The records from an 18th-century curator had determined the gnomon to have been shaped like a pig’s tail, so it was recreated in the same form in Parslow’s plastic model.

To use the sundial, you align it, so the tip of the gnomon’s shadow touches the vertical line for the month, and then you count the horizontal lines from the top line to the line nearest to the shadow. It is tricky to use as it moves in the wind, but it will tell the time within a quarter of an hour to half an hour, which must have been practical enough for the ancient Romans.