We now live in an age of constant astronomical revelations. Every day, new discoveries lead us closer to the answer of the perennial questions about the universe, how it looks, how it works, and if we are alone in it, or if we share it with other intelligent beings. Theories about the existence of extraterrestrial sentient beings are not new. People have always explored this idea, especially in Victorian times.

One planet was always the center of interest regarding this subject – Mars. Even today, scientists think that Mars is a good candidate for a planet that could have supported life in the past. One such scientist was Percival Lowell, but, it must be said, that his theory probably went too far.

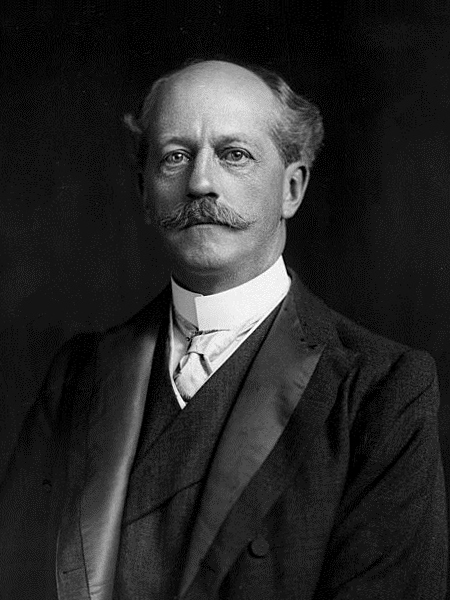

Born in a wealthy and influential Boston, Massachusetts family, he was the brother of Abbot Lawrence (President of Harvard University from 1909 to 1933), and Amy Lowell (American poet of the imagist school). Upon graduating from Harvard University with a distinction in mathematics, Lowell gave a speech on the nebular hypothesis – suggesting that the Solar System formed from a nebulous material. This was a subject considered very advanced for its time. During his life, Percival was always interested in the natural sciences and especially in Astronomy.

In 1892, Lowell was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and decided to move back to the United States. Since 1893, he completely devoted his life to astronomy, and with his wealth, he built an observatory. He built the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona Territory, at an altitude of over 2,100 meters (6,900 feet), on a location that was far from city light pollution. It became the first observatory deliberately placed in a remote location like this. Here, Lowell spent the last 23 years of his working life.

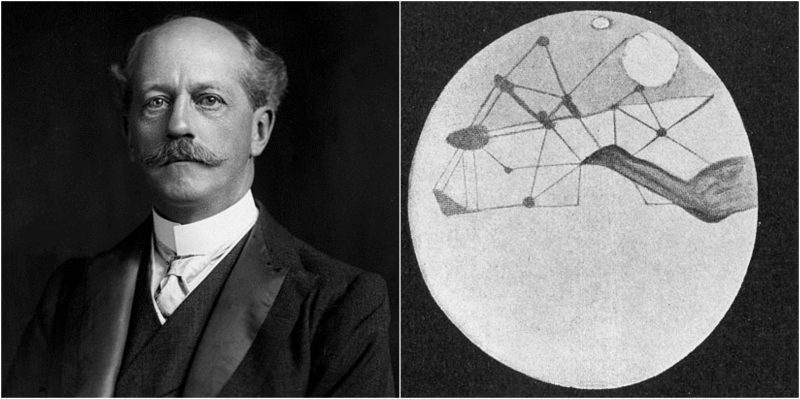

In his astronomical observations, Lowell focused his attention on Mars. His obsession with Mars was born after he read Camille Flammarion’s book “La planète Mars.” Lowell was very intrigued by the “canals of Mars” when he saw them in a drawing made by Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli, the director of the Milan Observatory. Lowell studied Mars for 15 years and in that process, he made detailed drawings of the surface of the planet in the way he perceived it. He gathered his research of the Red Planet in three books: “Mars (1895)”, “Mars and Its Canals (1906)”, and “Mars As the Abode of Life (1908).”

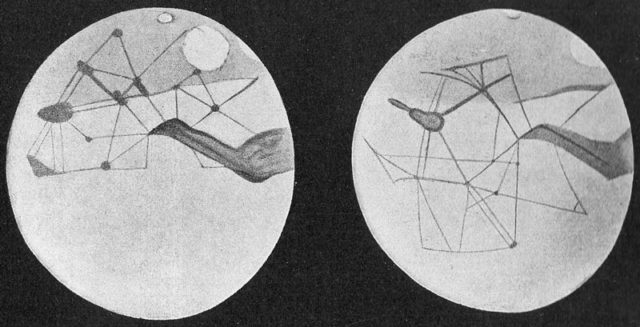

Although there were other scholars sharing Lowell’s opinion that the markings on Mars confirm the theory that the planet once sustained intelligent life, Lowell was the one who popularized the idea the most. In his analysis of the surface of Mars, Lowell spoke about “non-natural features,” among which were the “canals,” which he divided into single and double.

Lowell’s theory was that all of those “artificial” canal features on the planet were made by some advanced civilization in the act of desperation. He thought that they constructed the canals in order to tap the polar caps of the planet, their last source of water, and save their drying and dying planet.

The idea became very popular among the public, but those in the scientific community weren’t so sure about Lowell’s theory. Other astronomers from the time were skeptical and didn’t recognize the same markings on the surface as Lowell did. Those who saw the features as he did, didn’t believe that the network of canals was so big. Lowell’s work and his Mars theories received a lot of negative criticism from the scientific community. In order to prove (or disprove) Lowell’s claims, in 1909, the sixty-inch Mount Wilson Observatory telescope in Southern California was used to observe the features that he spoke about. The telescope, which was far more powerful than the one that Lowell had, revealed some geological features that were probably formed due to natural erosion.

Lowell’s “non-natural features” were once and for all disproved after NASA’s Mariner missions in the 1960s made some better images and scans of Mars.The Mariner missions revealed the cratered surface of the planet, and it turned out that those “canals” were just an optical illusion.

Ultimately, Lowell’s belief in the artificial nature of some features on Mars destroyed his career. This and the beginning of World War I deteriorated Lowell’s health. As a pacifist, he was devastated by the war, and his inability to prove his theory.

Nevertheless, he is praised as one of the most influential popularizers of science before Carl Sagan. Soon after, Lowell suffered a fatal stroke and died on November 12, 1916, aged 61. He is buried near his Observatory on a place called Mars Hill.