Though it is unlikely to find them in the Bible, many Easter traditions and customs have been around for many centuries. Despite the fact that they are part of a religious holiday, some of these customs are linked to pagan traditions, too.

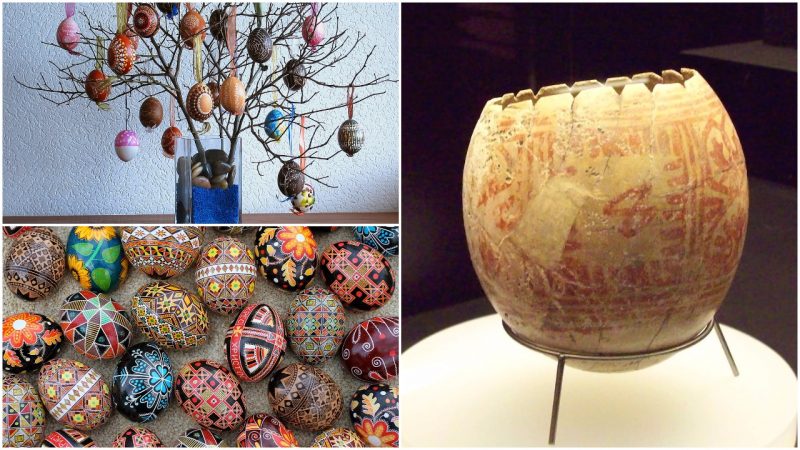

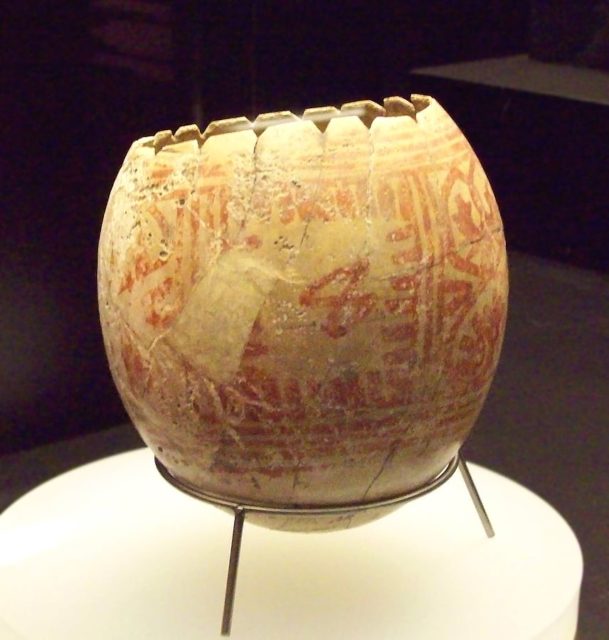

As an ancient symbol, the egg stands for new life and has been ultimately associated with pagan festivities which announce the awakening of the spring. Engraved ostrich eggs found in Africa are deemed to be as 60,000 years old and were probably purposed for spring rituals. Decorated ostrich eggs in gold or silver were frequently placed in the graves of ancient Egyptians and Sumerians too, about 5,000 ago. They were associated with death, rebirth, but also kingship and power.

Cross-cultures and different mythological narratives further speak about the creation of the world out of a cosmic egg. A great example is the Finnish work of literature, “The Kalevala”. The book is a 19th-century work of epic poetry compiled by Elias Lönnrot, and it is based on Karelian and Finnish mythology and oral folklore.

The narrative vividly incorporates the mythological image of cracking the cosmic egg and creating life on Earth. It begins by saying that at first the world was only a vast water surface and there was nothing else. Above it, there was a duck, and down was a deity who ruled over the waters. One day the duck needed a place where she could nest the eggs, and the water deity showed a knee to the bird. The duck had seven eggs, six golden and one made of iron. The eggs were nestled on the knee, but eventually, they all plunged into the water, creating the soil, the skies, the sun, the moon, and so forth.

When it comes down to painting eggs, such custom can be observed for many thousands of years in Persia as part of the Zoroastrian new year, the Nowruz (literally translates to “new day”). The Nowruz celebrations persist today among Iranians worldwide. In one of the customs, the colored eggs are part of the Nowruz dinner, and the mother of the family eats one egg for each of her children. Accounts suggest that this custom has been present even before the reign of Cyrus the Great, whose rule (580 BC to 529 BC) has marked the birth of Persian history.

The actualization of the egg customs in Christianity has occurred somewhere around the 13th century. A possible explanation of why this customs appeared may be that eggs were formerly a prohibited food likewise dairy or meat products during the Lenten period; people could eat them once the Lent was through. Nevertheless, looking back in time, there is not just one single answer to why we dye eggs.

According to Vol 5 of Donahoe’s Magazine, a US-based Catholic-oriented general interest magazine that was issued in between 1878 and 1908, the custom of the Easter egg may have existed in an early Christian community of Mesopotamia. They dyed the eggs in memory of the blood of Christ, shed at his crucifixion; the egg was also considered a symbol of Jesus’ empty tomb. Eventually, the church took up this tradition, and it has continued to thrive ever since.

Sociology professor, Kenneth Thompson contemplates about the spread of the Easter eggs customs. He writes that “use of eggs at Easter seems to have come from Persia into the Greek Christian churches of Mesopotamia, thence to Russia and Siberia through the medium of Orthodox Christianity. From the Greek Church, the custom was adopted by either the Roman Catholics or the Protestants and then spread through Europe.”

The legends teach us that Mary Magdalene was a key player in the creation of the egg-dying tradition. One version of the story suggests that Mary Magdalene had visited the tomb of Jesus three days after the crucifixion. She carried a basket filled with prepared eggs that she wanted to give to the other women who would be mourning at the grave. When she arrived, though, the stone rolled away, showing the tomb empty. Eggs allegedly turned red in that instance.

Another version of the legend tells of Mary Magdalene’s visit to the Roman Emperor Tiberius after Jesus’ resurrection.

She had greeted Tiberius with the words “Christ has risen”, but in disbelief, the Emperor had answered that “Christ has no more risen than that egg is red,” while pointing to an egg that was either on his table or held by Mary (depends on which version of the story you read). At that moment, the eggs turned red.

Eastern European legends suggest that it was Jesus’ mother Mary who brought up the tradition of egg-dying. Mary was present at her son’s crucifixion on Good Friday, and supposedly she had eggs with her. In one of the versions, blood spilling from the wounds of Jesus dropped on the eggs and colored them red.

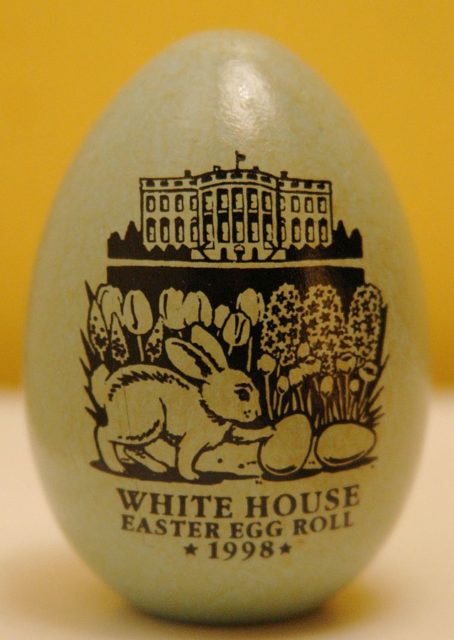

Last but not least, King Edward I of England may have well contributed to the customs of decorating eggs for Easter. Reportedly, during his reign in the 13th-century, he ordered 450 eggs to be colored and decorated with a golden leaf, after which they were presented as Easter gifts to the rest of the royal household. It is likely that his example was followed by others as well.

Today, Easter is one of the favorite holidays in the Christain world. Easter has also emerged as the second biggest candy-consuming holiday of the year, following up Halloween.

Read another story from us: The origins of the Easter Bunny and Easter eggs

Luckily, these two holidays are six months apart- perfect for the annual check-ups at the dentist!