The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World is a well-known list of the most impressive constructions from classical antiquity. Even today, they never fail to dazzle the human imagination.

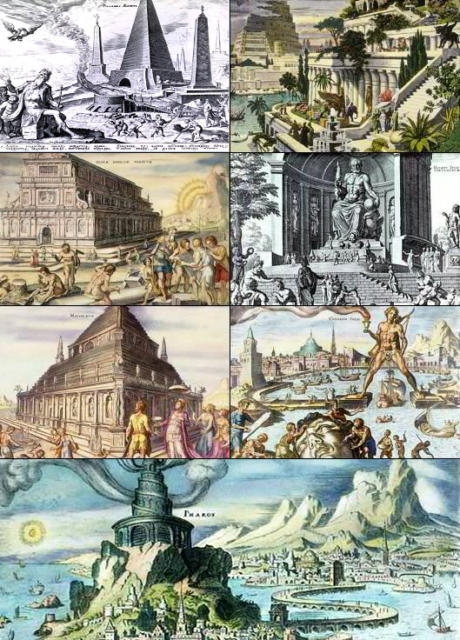

As most of us know, only the Great Pyramid of Giza, the oldest of the ancient wonders, has survived to present day. The Colossus of Rhodes, the Lighthouse of Alexandria, the Statue of Zeus, the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, and the Temple of Artemis are all sadly gone, and we will never see their beauty as the ancients did.

The final item on the list, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, has disappeared as well, although nobody is quite sure where exactly it was in the ancient world. In fact, some historians speculate that this seventh wonder might have never existed at all.

Today we have many literary accounts of these architectural masterpieces from ancient travel pamphlets and poems, especially from Greece. The set list of seven as we know it today did not emerge until the Renaissance, though.

By the fourth century BC, the Greeks had conquered much of the then-known world. They came into contact with many ancient civilizations like the Egyptians, Persians, and Babylonians. Astounded by the grand buildings of these societies, Greek travelers began to record what they saw. Consequently, the first writings that referred to a list of wonders of the world appeared around the first century BC, in Greece.

At first, the ancient Greeks spoke of “theamata,” meaning “sights,” or “things to be seen” (Tà heptà theámata tēs oikoumenēs [gēs]). The word “wonder” came around later. Diodorus Siculus, a first-century BC Greek historian, provided one of the first references to a list of seven landmarks. The poet Antipater of Sidon, who lived around 100 BC, mentioned a list as well. He described the wonders in a poem, which goes as follows:

“I have set eyes on the wall of lofty Babylon on which is a road for chariots, and the statue of Zeus by the Alpheus, and the hanging gardens, and the Colossus of the Sun, and the huge labor of the high pyramids, and the vast tomb of Mausolus; but when I saw the house of Artemis that mounted to the clouds, those other marvels lost their brilliancy, and I said, ‘Lo, apart from Olympus, the Sun never looked on aught so grand.'” — Antipater, Greek Anthology IX.58

Philo of Byzantium also produced a short writing called “The Seven Sights of the World,” which only survives in fragments. It covers six of the supposed seven wonders, and matches up with Antipater’s description. There were earlier lists too, from the historian Herodotus and the architect Callimachus of Cyrene, but these survived only as references in the Museum of Alexandria.

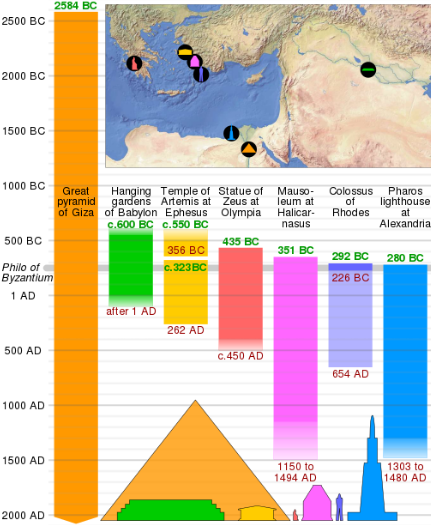

According to literary accounts, the Colossus of Rhodes was the last of all seven wonders to be completed, probably around 280 BC. It was also the first of the seven to be destroyed, by an earthquake around 226-225 BC. This means that all seven landmarks would have existed at the same time for fewer than sixty years.

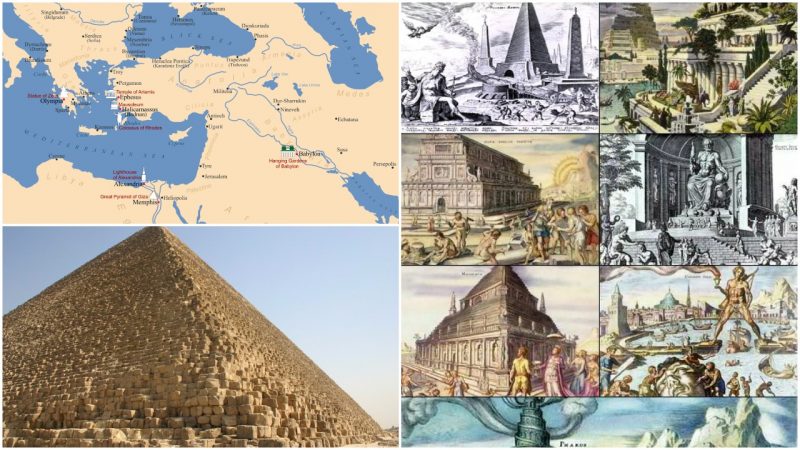

Most of the landmarks were around the Mediterranean, with the exception of Babylon. This was the world as the ancient Greeks knew it, so sites beyond this realm were never considered. Five out of the seven wonders are in fact Greek architectural and artistic accomplishments, which did not go unnoticed by Hellenic writers. Only the Egyptian Pyramids of Giza and the mysterious Mesopotamian Hanging Gardens of Babylon were non-Greek.

The Temple of Artemis and the Statue of Zeus were destroyed by fires, while the Lighthouse of Alexandria, Colossus of Rhodes, and the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus all fell in violent earthquakes. Sculptures from the Mausoleum, as well as some from the Temple of Artemis, survived — they can now be seen in the British Museum in London, England.

This practice of cataloging the greatest human architectural achievements continued beyond the times of Ancient Greece. Later Romans similarly indexed wonders from around their empire, reflecting the rise of Christianity and celebrating both Roman and Christian sites. Such lists included the Colosseum in Rome and Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem, incorporating the traditional pagan culture with those of the Eastern Mediterranean.

Read another story from us: The Colossus of Rhodes – One of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World

Writers continued to produce lists of wonders throughout the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, and even as recently as 2006, as people continue to celebrate their contemporary achievements of engineering. The original list of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World may never be surpassed in grandeur, though, having set the standard for such a practice.