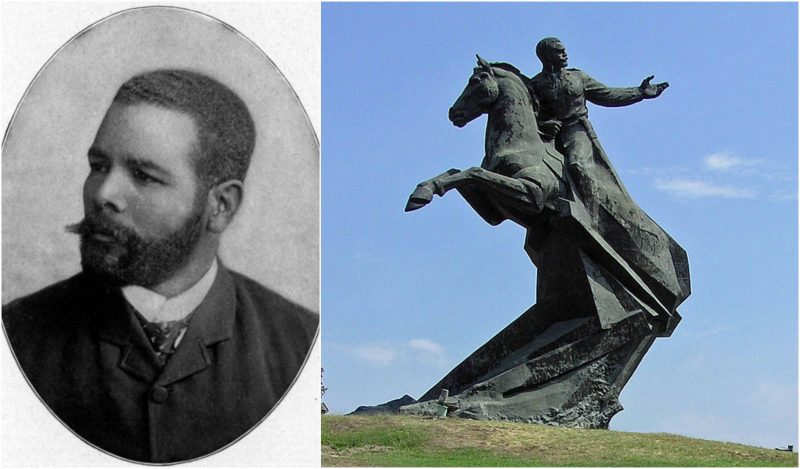

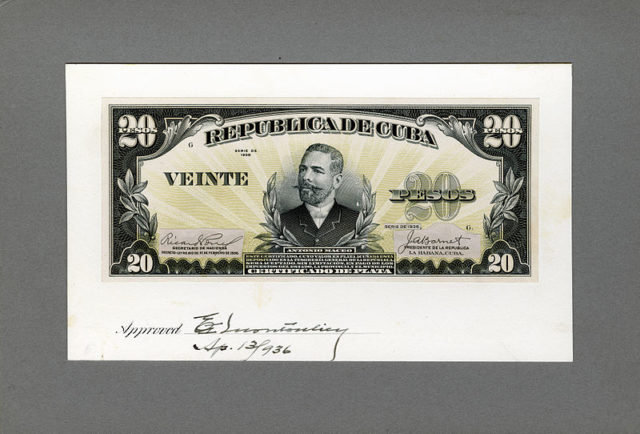

Lt. General José Antonio de la Caridad Maceo y Grajales (or, Antonio Maceo Grajales) was second-in-command of the Cuban Army of Independence.

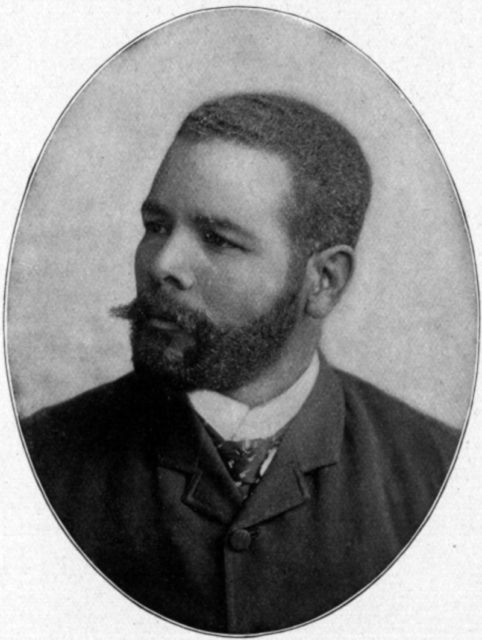

Fellow Cubans gave him the nickname “El Titan de Bronce” (“Bronze Titan”), because of his strength in battle and his skin color. Spaniards, on the other hand, called him “El Leon mayor” (“Greater Lion”). Maceo was one of the most notorious guerrilla leaders in Latin America during the 19th century.

Maceo was born in 1845 in the town of San Luis in Cuba. His mother was an Afro-Cuban woman of Dominican descent, Mariana Grajales Coello, who was a feminist icon in Cuba as well as an advocate for Cuban freedom from slavery. Maceo’s father was Marcos Maceo, a farmer and dealer of agricultural products from Venezuela. In his youth, Marcos Maceo had fought on the side of the Spaniards, against the forces for independence led by José Antonio Páez, Simón Bolívar, and others. After some of his comrades had been exiled from South America, Marcos Maceo left Caracas and moved to Santiago de Cuba.

While Maceo’s father taught him the skills of working and managing their property, his mother was the one who gave him his sense of order. Mariana’s discipline was crucial in the development of Maceo’s character, which became important in his acts as a military leader.

When he was sixteen, Maceo started working with his father, delivering supplies by mule. By this age, he was already a successful farmer and entrepreneur. He became actively interested in politics and joined the Cuban Freemasonry movement, which was influenced by the principles of the French Revolution — “Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity” — as well as the Masons’ main guidelines: God, Reason, and Virtue.

After “The Cry of Yara,” a revolt against Spain led by Carlos Manuel de Céspedes in 1868, Maceo (along with his father and brothers) joined the war for Cuban independence. His mother went to the woods to support the mambises, female guerilla fighters. When the Ten Years’ War began, Maceo enlisted as a private and quickly climbed through the ranks, becoming a commander and then a lieutenant colonel in less than six months. Later, Maceo was promoted to colonel, and within five years he earned the rank of brigadier general.

He fought in more than 500 battles, and the men under his command started calling Maceo “The Bronze Titan” due to his exceptional strength and resistance to blade or bullet injuries. Maceo recovered from more than 25 injuries and always led his troops into combat with enthusiasm. He was the war teacher of the great Máximo Gómez, a Dominican strategist who became the General-in-Chief of the Cuban Liberation Army and whose use of the machete as a battle weapon was adopted by Maceo and his troops.

Maceo was one of the few officers who opposed the signing of the Pact of Zanjón, which ended the Ten Years’ War. Together with other guerillas, Maceo met with General Arsenio Martínez-Campos in March 1878 to discuss peace terms. However, Maceo argued that the only benefit would be the amnesty for those involved in the conflict and liberty for the black soldiers who fought in the “Liberator Army.” In his mind, real peace would only have been achieved if slavery was completely abolished in Cuba, and the country gained independence. Thus, Maceo didn’t recognize the treaty as valid, so he didn’t adhere to the proposed amnesty.

When he was invited to a meeting known as the Protest of Baraguá, which planned to launch a sneak attack on the Spanish general, Maceo rejected the idea and wrote in a letter, “I don’t want victory if it goes accompanied with dishonor.” A few days later, Maceo resumed hostilities. The government of the Republic of Cuba ordered him to gather arms, money, and men for an expedition from the exterior, to save his life.

In 1879, while in New York with General Calixto García Íñiguez, Maceo planned a new invasion of Cuba which resulted in the short-lived Little War. Although Maceo didn’t fight in these battles, he sent Calixto García as his highest commander.

In the meantime, Maceo was haunted by the Spanish in every way possible. In Cuba, they spread racial propaganda, which damaged his reputation in the eyes of the people. Maceo stayed in Haiti for a while, but the Spanish pursued him and tried to assassinate him. So, he escaped to Costa Rica, where the president assigned him to one of the military units and allowed him to settle on a small farm.

The War of 1895 began when Maceo was contacted by Jose Marti, who urged him to join the “necessary war.” After escaping assassination attempts by the Spaniards in Haiti and Baracoa, Maceo and his officer Flor Crombet escaped and hid in the mountains. He managed to gather a small group of armed men, which slowly grew over time.

After Maximo Gomez had become General-in-Chief of the Cuban Liberation Army, Maceo was designated Lieutenant General (second in command). Together the two men started from Mangos de Baraguá, controlling two long columns of mambises, and with exceptional proficiency invaded the west of Cuba. Even though the Spanish forces outnumbered the Cubans five to one, Maceo and his mambises advanced slowly.

In 1896, Maceo was planning to meet Gomez in Havana to plan the next course of the war, but their meeting never took place. On December 7, 1896, Maceo was heading to the farm of San Pedro near Punta Brava, accompanied by his personal escort of two or three men. Trying to cut a fence next to the road, the men were spotted by a large Spanish column, which immediately opened fire. Maceo was hit twice. One bullet ended up in his chest while the other broke his jaw and penetrated his skull. Not knowing the identity of the fallen men, the Spaniards left the bodies and continued on their way.

Read another story from us: Granma Yacht: the vessel which brought the Cuban Revolution in Cuba

After hearing the news, Colonel Aranguren immediately ran from Havana to pick up the corpse of Maceo. The bodies were secretly buried on a nearby farm belonging to two brothers, who kept the location a secret until Cuban independence was achieved. Scholars say that Maceo’s death was as traumatic to Cuban patriots as José Marti’s.