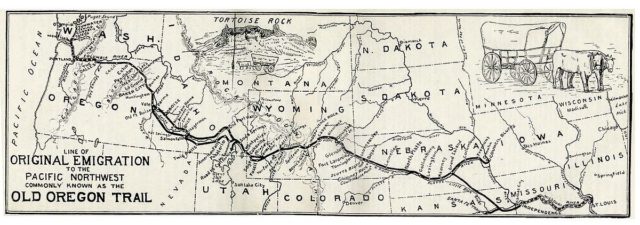

Extending across half the continent and snaking more than 2,170 miles through territories that would later form Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, Idaho, and Oregon, the Oregon Trail was the essential route that pioneers used on their way to the West.

The great encounters would pass through spacious plains, rolling hills, and vivid mountainous passes. The journey would begin in Independence, Missouri, and end at the Columbia River in Oregon. While the routes were first used by American fur hunters in the 1820s, the real heyday of the trail was a few decades later, when thousands of pioneers followed the trails blazed by Native Americans in order to reach the West Coast.

For those who remember, there was even a classic computer game back in the day, also called “the Oregon Trail.” While the real excitement among gamers came down to managing all the misfortunes and challenges of their own wagon on the trail, they also stumbled upon several landmarks along the way. Be it the Kansas River, Chimney Rock, or Independence Rock, even the most enthusiastic players would not know what kind of relics still lurk on the course of the real tracks.

We gathered some of the most interesting

California Hill – Brule, Nebraska

Close to North Platte, Nebraska, the Platte River divides into two big forks. The South Platte continues to run smoothly southwest toward Denver, and the North Platte heads to the northwest towards Fort Laramie. Pioneers also needed to cross the South Platte so they could reach and follow the North Platte, and then go towards South Pass.

A couple of crossing points were used, but the Upper Crossing was of the utmost importance as it led directly to Ash Hollow, which was the best approach to the North Platte River. There, they would encounter the California Hill, which was a struggle to climb. Ascending some 240 feet in just a mile and a half, some imposing trail ruts can still be seen going way up the hill. This site was one of the major climbs that pioneers needed to pass on the trail.

Guernsey Ruts – Guernsey, Wyoming

Perhaps some of the most impressive remnants of the historic Oregon Trail are found at Guernsey. Almost every pioneer here went past the same spot, moving over soft sandstone.

The thousands of wagons determined to reach the West carved deep ruts into the sandstone. Each wagon would eventually wear down the rock, little by little, and the ruts, over time, became five feet deep. The site is also known as Deep Rut Hill, and history has certainly left a mark here.

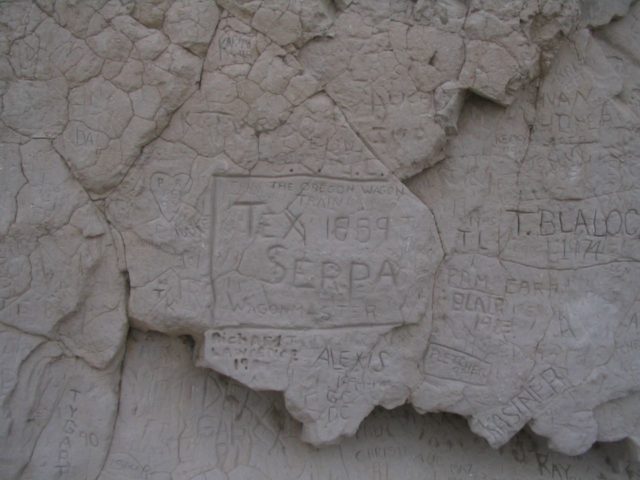

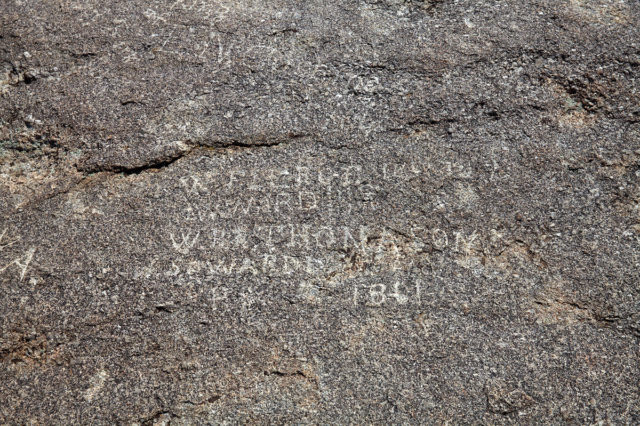

Nowadays, visitors can freely walk through the deep ruts and say that they’ve had a real pioneer experience. South of Guernsey is also the Register Cliff, where many emigrants carved their names into the rock, to commemorate their passage.

One other such point where people used to carve their names was Alcove Spring, earlier on the route, in Kansas. Authentic rock formations, a waterfall, and a natural spring compose the site, which was also a favorite stopping point for pioneers after crossing the Big Blue River.

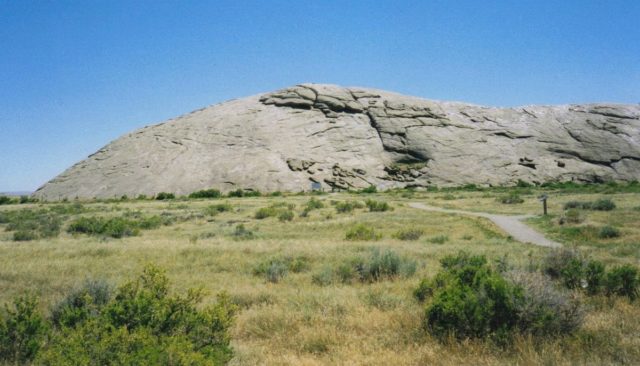

Independence Rock – Casper, Wyoming

Looking like a giant stone turtle, Independence Rock extends over 27 acres just next to the Sweetwater River. Being 700 feet wide, 1,900 feet long, and 136 feet tall at its highest, this landmark stands as tall as a 12-story building. Whoever missed the opportunity to carve their name at Alcove Spring or Register Cliff was certainly able to do so here.

The pioneers were not the first to have left carvings on the gigantic granite monolith, though. Many Native American tribes that ranged the central Rocky Mountains, such as the Arapaho, Arikara, Lakota, or Shoshone, just to name a few, also visited the rock.

Since it also gained popularity among the pioneers, it was later dubbed the “registers of the desert.” Over three decades of intensive migration, almost half a million Americans would pass by Independence Rock on their path to the unknown frontiers. Thousands of them inscribed their names on the monolith.

Big Hill – Montpelier, Idaho

Big Hill was probably the longest and steepest hill of all on the trail. The climb was fairly hard, but its descent even worse, and far more dangerous.

Tracks can still be seen going up the hill, as well as on the way back down, toward Bear River Valley. The trail runs alongside US Highway 30. Through the Bear River Valley, the road would lead toward where Montpelier is today, and then along the natural wonder of Soda Spring.

Virtue Flat – Baker City, Oregon

Just below today’s National Historic Oregon Trail Interpretive Center of Flagstaff Hill, where emigrants would get their first glance at the Baker Valley, there are seven miles of wagon ruts to be seen going across the terrain.

Some of the ruts are parallel to one another, perhaps as wagons would pass by each other in a hurry. Whoever was slower would fail to reach Powder River first. An arid segment composes the terrain, but the real obstacle for the pioneers here were the shoulder-tall sagebrushes.

However, very soon the travelers would be greeted with their first glimpse of the promised land beyond, as this part of the historic trail actually represents the first passing lanes in the west. In the distance, the Blue Mountains would also welcome the newcomers, assuring them they were coming closer to the long-awaited Willamette Valley. The trail would end farther along at the Columbia River.

Many modern highways are close enough to the places where the Oregon Trail has left its historic mark. With a little effort, the curious eye will notice them. Many of the pioneer trails are designated as National Historic Trails, too.