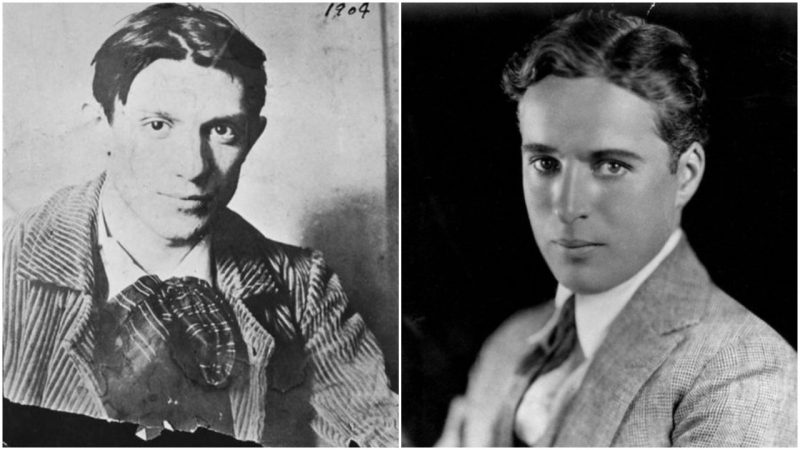

You might be surprised to discover that two of the most eminent bards of art and cinema of the 20th century, Charlie Chaplin and Pablo Picasso, had much in common. And it’s not just their fame and wealth. Both born in the 1880s but in different parts of the world, they couldn’t exchange a word in the same language. However, they had followed similar paths before they finally met in Picasso’s studio in rue des Grands Augustins in Paris, an encounter described as a celebratory collision of two healthy, if not bloated, egos.

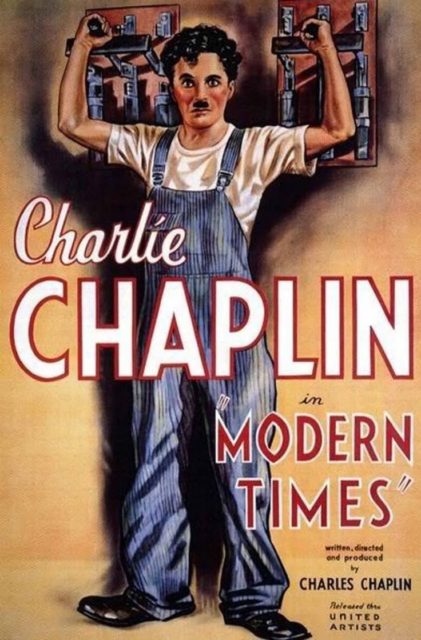

The careers of the two geniuses did diverge. The poised Picasso remained master of his art for almost five decades whereas Chaplin was threatened by a potential crisis when silent films were replaced by the “talkies.” He had to reinvent himself as a director, filming Modern Times and The Great Dictator in the 1930s, contributing political engagement to contemporary cinema.

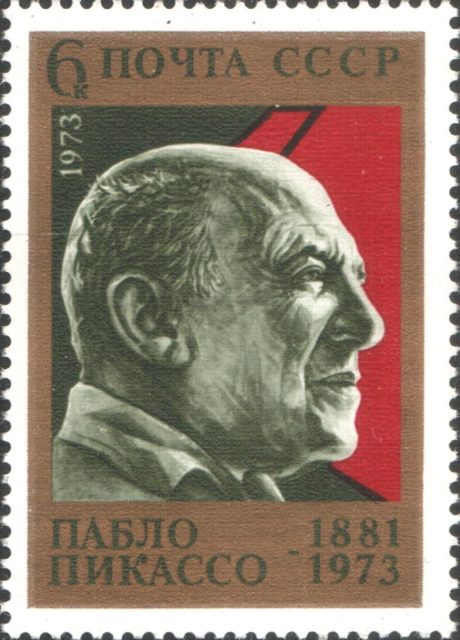

Nevertheless, the trait that undoubtedly linked Picasso to Chaplin was their strictly left-wing outlook and their sympathy for Soviet Russia, looking down on the Western world to a certain extent.

Chaplin supported the Soviet Union during the war, also backing the Progressive Party in the U.S. In the Cold War climate of the U.S., he was condemned by some politicians. When he left the country to promote a film in England, the attorney general revoked Chaplin’s re-entry permit and said he would have to be interviewed on his politics and his morals before he could return. Picasso, a Spanish national, was refused citizenship of France in 1940 due to his Communist ideals; however, he continued to live in the city for some years.

They were both short in stature, but definitely virile; their height didn’t stop them from being infamous womanizers. They each had a passion for young women. Chaplin’s sex life was often a case for public disapproval in America, while Picasso had an easier time of it in the rather lenient France, such as seducing Marie-Thérèse Walter when she was 17 and he was a married 45-year-old.

Chaplin and Picasso were both considered to be “increasingly anti-American but too benign for the USSR.” On the one hand, Chaplin was proud that The Great Dictator was banned by Hitler. However, Stalin also censored the film because of the scene in which the first man who stopped applauding a speech by the Great Helmsman Stalin was a dead man. Russia also rejected his film Modern Times because, reportedly, it was weak on socialism.

Picasso’s portrait of Stalin in the weekly “Les lettres francaises” provoked sharp criticism from the party, mainly because its lack of the so-called “realist art,” which praised Communist utopian ideas. His avant-garde painting was unacceptable to the Soviets as they looked upon it as art influenced by Western ideals. So, despite Chaplin’s and Picasso’s admiring sentiments towards the Soviet Union, they faced a paradox as their work would not be shown there.

In 1952, Chaplin faced an implicit boycott of his new film Limelight in the U.S. and reportedly U.S. Attorney General James P McGranery, a strong Catholic, accused him of “making statements that would indicate a leering, sneering attitude toward a country whose hospitality has enriched him,” threatening a permanent exile from America. Chaplin and his family moved to England, or as he called it “my country,” an attribute that quickly faded away as he faced the draconian taxes endured by the upper social classes. Despite his political views, he was determined to live as an elite. Soon after, the Chaplins headed to Paris, Picasso’s place of residence.

At the time, Picasso had already joined the Communist party, after the Liberation of Paris, and for eight years maintained a high status in the Party. One night, during a dinner party organized by the leading Communist writer Louis Aragon, Picasso met Chaplin, who told him that he was a big fan. Soon followed an invitation to Picasso’s studio, which Chaplin gladly accepted, bringing his wife along with him. Reportedly, the evening enjoyed quite a vivid atmosphere despite the language barrier between these two bards, with Aragon translating. Picasso seemed to have an adverse opinion of Limelight. Chaplin’s response was to dance the New Year’s Eve sequence in The Gold Rush, prompting huge applause, leaving Picasso thrilled.

Related story from us: Albert Einstein and Charlie Chaplin were close friends

The ladies’ man he was, 71-year-old Picasso couldn’t take his eyes off Chaplin’s fourth wife, 27-year-old Oona O’Neill, and openly expressed his desire to get to know her better, a statement that was lost because, luckily, Aragon decided to forget his English.

According to some biographies, the Chaplins spent two weeks in Moscow along with Picasso and Aragon as part of Stalin’s birthday ceremonies, before they headed to Switzerland to find a convenient home for their long exile.