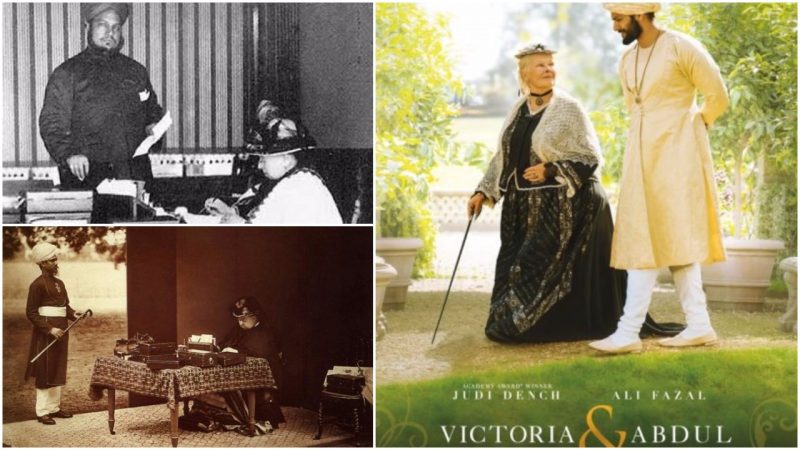

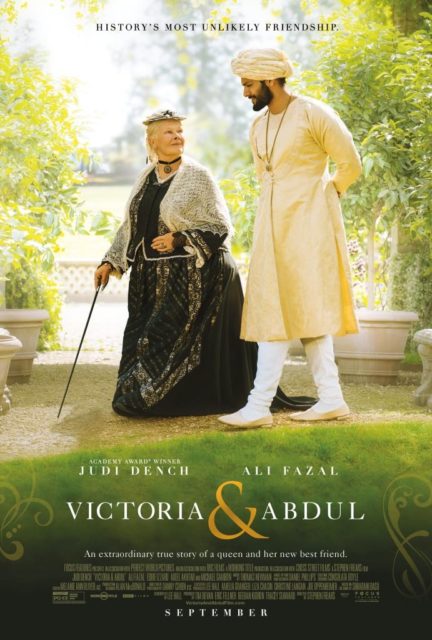

The master and servant relationship has roots in slavery and serfdom, and for a long period of time, despite the inherent inequity, it was regarded as something natural, almost as important as the relationship between spouses or parent and a child. The master and servant dynamic between Queen Victoria and her most dear Munshi, the Indian clerk Abdul Karim, went through many incarnations. It is such a fascinating relationship that it will be the subject of a new film, Victoria & Abdul, starring Judi Dench and Ali Faza and set for release September 22nd.

Mohammed Abdul Karim’s journey to Britain took him from Agra to Bombay by rail, and then via a mail steamer to reach the British Isles. He arrived at Windsor Castle in June 1887 to represent India to the Queen, the nation that was the “jewel in the crown.” Impressed, Queen Victoria, then 68 years old, decided that Karim should be one of her personal servants.

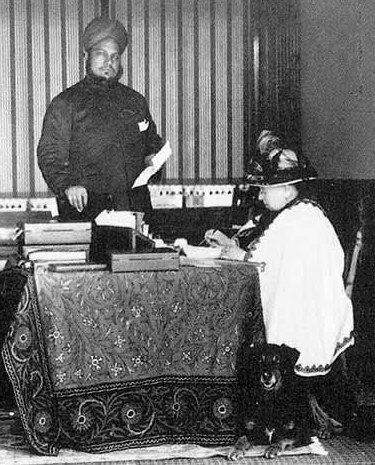

In the beginning, he was supposed to serve the Queen at breakfast. After their very first encounter, the Queen would describe Karim in her diary, writing: “The other, much younger … with a fine serious countenance. His father is a native doctor at Agra. They both kissed my feet.”

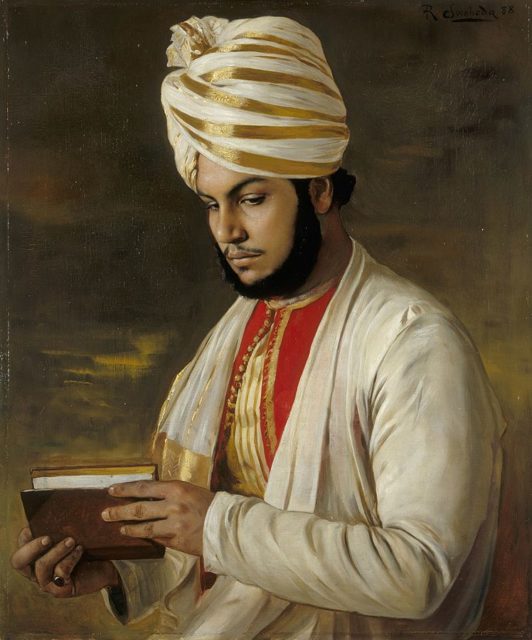

Only one month later, the Queen would also remark in her diary that she was now learning some words in Hindustani, so she could speak in their tongue to her servants. She would note that learning more about the Indian language and people was of great interest to her, and by the end of August 1887, she would have Abdul Karim teaching her Urdu. She then give him the title of “Munshi,” which in Urdu means “clerk” or “teacher.”

Karim was the first Indian clerk to have served the Queen, and perhaps their master-servant relationship worked so well because he was a doorway to this entirely different and new world, one that the Queen had never had the chance to experience directly. But, after all, she was not only the Queen of the United Kingdom but also of the whole British Empire and had even adopted one more title: the Empress of India.

Karim’s biographer, Sushila Anand, provides one more angle to the story, suggesting that the Queen’s letters are proof that the conversations between the two had been widely “philosophical, political and practical,” and that both of them engaged with full minds and hearts.

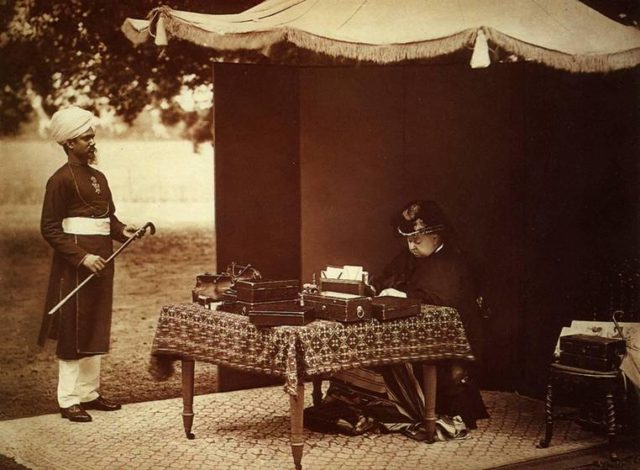

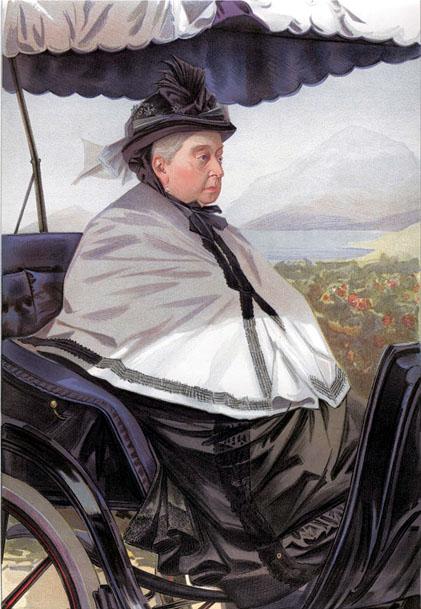

Taken in the Garden Cottage at Balmoral, 1894 or 1895.

As time passed, Karim progressed in the Royal Household. Soon enough, he was also in charge of all the other Indian servants. Queen Victoria kept praising him, giving him all kinds of compliments: being a good, very refined gentlemen, comforting and understanding, clever and excellent, to name just a few.

The Queen decided to help Karim on personal matters, such as assisting his father to obtain his pension or a former employer in India getting promoted. Karim would also bring his wife and mother-in-law to stay for a while in Britain, and the Queen personally met with all of them, sometimes accompanied by other notable royals such as the Empress of Russia, Maria Feodorovna.

Karim’s distinct position started to nurture dissatisfaction and uneasiness among other members of the Royal Household. Being a man of ordinary Indian status, almost nobody else except the Queen was in the mood to welcome Karim into the close circle of the royals. This angered Queen Victoria very much, while for his part, Karim supposedly expected to be treated as an equal by the others of the court.

During an entertainment event dedicated to the Queen and hosted by Albert Edward, Prince of Wales and the future King Edward VII, at his home in Sandringham in 1889, Karim was seated with the lower servants. It was considered that the dark-skinned Indian could only be of the most lowly status.

Karim retreated to his quarters early that night, and the Queen, angered by such race hatred, would allegedly make a point that the “dear good Munshi” deserved nothing but respect. Victoria was immensely influenced by her Indian servant and accounts tells us she tolerated almost anything he did, disregarding any complaint made about Karim.

In June 1889, when Karim’s brother-in-law had been invited for a stay at Windsor, he was found selling one of Victoria’s brooches to a local jeweler. The Queen then quickly accepted Karim’s explanation, that his relative had found the brooch and Indian customs suggest that whoever finds a possession is bound to keep it. Everybody else, of course, thought that the brother-in-law had the brooch stolen.

A few months later, the Queen went to stay with her Munchi at Glassalt Shiel at Loch Muick, a remote house on the Balmoral estate, the Scottish holiday home of the royals. To everyone’s anxiety, the Queen had often stayed there with John Brown, a personal servant and a favorite of hers before Karim. But after Brown’s death, she vowed never to return to the remote house again.

It was a close and platonic relationship perhaps like none other. When Karim had surgery, the Queen visited him twice each day. Had the Queen a need to travel somewhere or attend a Royal gathering, the Munshi also needed to accompany her. This only proceeded to fuel friction among other members of the Royal Household, prompting serious arguments.

In other instances, the royal family had alleged that Karim was even spying for the Muslim Patriotic League, swaying the Queen against the Hindus. Queen Victoria dismissed such claims, saying it was only because of “race prejudice” or jealousy.

Following Queen Victoria’s death in 1901, her successor, King Edward VII, ordered that Karim return to India and he also had asked the entire correspondence between the two confiscated and destroyed. For the rest of his life, Karim lived near Agra, on a property that the Queen secured for him in advance. Karim would pass away eight years later, at the age of 46.

The movie Victoria & Abdul is to portray this unique relationship on the big screen. Scheduled for release this fall, the film depicts the relationship between her Majesty and her Munchi. Judi Dench, Ali Fazal, Eddie Izzard, Tim Piggot-Smith, and Adeel Akhtar are starring in the film.

We don’t know about you, but we can’t wait to see it!