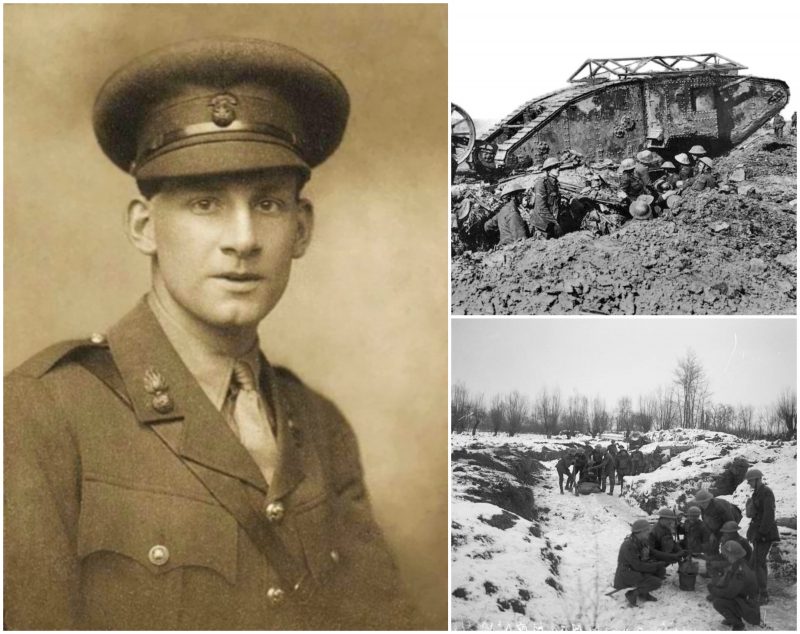

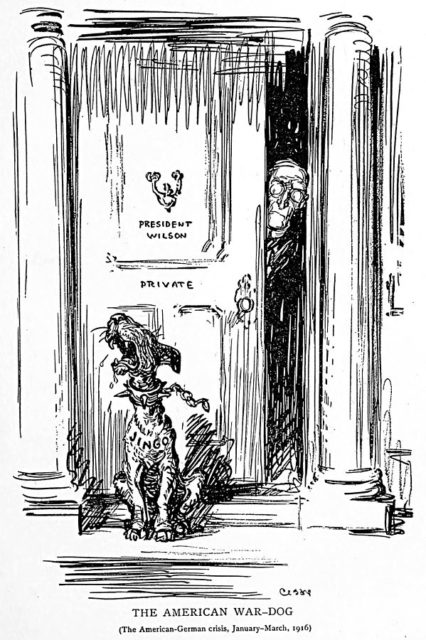

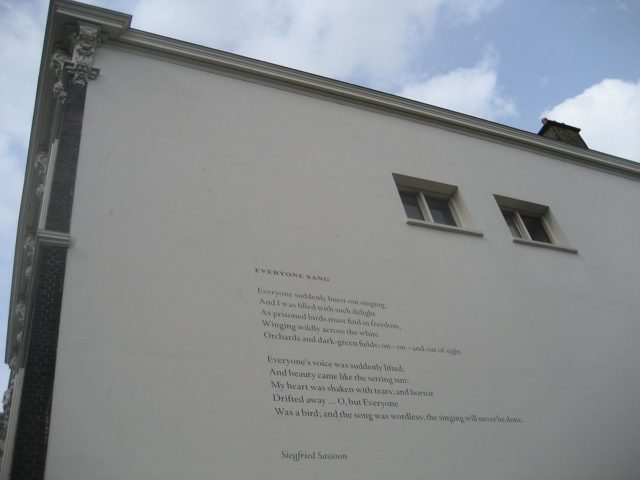

The poet Siegfried Sassoon is best remembered among his fellow soldiers in World War I as “Mad Jack” for his sheer bravery in combat and acts of courage in the face of danger. He also gained both good and bad publicity with his highly influential anti-war poems that satirized patriotic pretensions and jingoism, sharply criticizing the war while veering away from sentimentality.

Sassoon found ways to channel the horrors of war through poetry, depicting the unimaginable brutality of trench warfare, the ill-natured policies, and spewing vitriolic criticism at the clergy for blind support of bloodshed.

He endured many instances of war horrors. He went headfirst into battle and saw the deaths of friends, fellow soldiers, and his brother. He even got shot in the head mistakenly by friendly fire and narrowly escaped death. The fiery scenes of carnage and the absurdity of war were precisely reflected in his passionate poetry.

Born to a wealthy family on September 8, 1886, in Kent, the young man lived a lavish life as a country gentleman, hunting fox, writing poetry, and playing cricket. He left Cambridge University without a degree, but his plan for becoming a poet was crystal clear. In his early poems, he praised the distinctive longing for the simple English country life.

After meeting with the prominent poet Robert Graves in the 1st Battalion in France, he was highly influenced by Graves’s gritty realism and his philosophy of “no truth unfitting.” Details such as rotting corpses, suicide, deep wounds, bravery, cowardice, and hate-filled patriotism are all trademarks of his work at this time. All this had a significant impact on sparking the literary movement of modernist poetry.

Following the outbreak of the First World War, Sassoon, like many young English soldiers, was full of patriotic enthusiasm, poised to serve his country. He joined the army just before the war was declared but he avoided combat until 1915 due to a broken arm.

He first served as a trooper in the Sussex Yeomanry, then with the Royal Welch Fusiliers, and saw his first action in late 1915 in the French trenches. He received many honors and was decorated twice: a Military Cross for continually bringing back wounded soldiers while under heavy fire, and another one for his reckless charge against a trench full of 60 German soldiers, dispatching them using only hand grenades.

At first light-hearted and privileged, with a naturalistic worldview, he remained optimistic about the WWI campaign for a time, but he changed his opinion with every battle he fought, starting with the bloody carnage of the Somme offensive of July 1916.

Significant factors in Sassoon’s changing attitude toward the war was the death of his younger brother in November 1915 in the Gallipoli Peninsula, his meeting with acclaimed war-poets Wilfred Owen and Rupert Brooke and anti-war intellectual Bertrand Russel, and the death of his dear friend David Cuthbert.

Encouraged by the pacifist worldviews of Bertrand Russell and after witnessing too much death by the hands of irresponsible commanders, a disillusioned Sassoon decided to take a public stand against the war by writing a letter to the Times in 1917:

“I am making this statement as an act of wilfull defiance of military authority because I believe that the War is being deliberately prolonged by those who have the power to end it.”

Believing that the war was being unnecessarily prolonged by the decisions of generals and politicians who followed their own interests while disregarding the lives of the young soldiers, he soon became a focal point for dissent within the English army and caused quite the controversy and public outrage because this letter was coming from a decorated soldier such as himself.

It was only the intervention of his friend and fellow poet, Robert Graves, that saved him from being court-martialed. He convinced the authorities that Sassoon was shell-shocked from the war, which impacted his thoughts.

He was promptly sent to Craiglockhart War Hospital in Edinburgh to recuperate and narrowly avoided a serious court martial. There he met Wilfred Owen, and the two men developed an intense and mutually influential friendship. Despite almost getting court-martialed, Sassoon returned to active duty in 1918. Sadly, Owen died a week before the war ended, thus throwing Sassoon in a deep depression.

Nevertheless, his most highlighted moment on the battlefield was on July 4, 1916, during the First Battle of the Somme. Sassoon, armed only with a bag of Mills bombs on his back (and a dash of sheer luck), decisively stormed a heavily guarded enemy trench at Mametz Wood in the Hindenburg Line.

Strongly believing that signaling for reinforcements was futile, he instead hid in the German trench and began reading a book of poems that he had brought with him.

In broad daylight, he solely went over with bombs, supported under safe covering fire from a couple of friendly rifles, and successfully managed to scare away the occupants. As he ran through the line, he pulled the safety pin with his teeth for throwing the grenades at a faster rate. The two-handed approach managed to scatter a trench full of 60 hardened German soldiers.

When he returned from the German trenches, he did not even bother to report. Colonel Stockwell, who was in command of his company, was furious by Sassoon’s reckless act of bravery and raged at him:

“I’d have got you a D.S.O., if you’d only shown more sense.”

For his daring single-handed (or two handed) storm on the German trenches, he was awarded a well-deserved Military Cross for gallantry in the same month. He was also recommended for the Victoria Cross. Sassoon skillfully used a practical method of using grenades in each hand at once and the innovative method proved to be very useful for crowded trenches.

On July 27, 1916, Siegfried Sassoon was awarded the Military Cross. The citation read:

2nd Lt. Siegfried Lorraine [sic] Sassoon, 3rd (attd. 1st) Bn., R. W. Fus.

“For conspicuous gallantry during a raid on the enemy’s trenches. He remained for 1½ hours under rifle and bomb fire collecting and bringing in our wounded. Owing to his courage and determination all the killed and wounded were brought in.

Sassoon’s bravery was so inspiring, that the soldiers of his company said that they felt imbued with confidence when he accompanied them. He demonstrated fearless efficiency as a company commander, often going with bombing patrols during night-raids, without a single scant for his own safety.

After the war, he continued a successful career in writing and retired from the army on healthy grounds. Additionally, he has briefly involved himself in politics and the Labour movement, as well as bitterly publishing Wilfred Owen’s poetry, cementing his reputation. His fictionalized autobiographies written in three novels, The Sherston Trilogy, have been very successful.

Siegfried Sassoon will always be known for his dangerous acts of courage. Robert Graves precisely described Siegfried as a near-suicidal soldier, hardened by seeing his fellow company endured absolute misery, thus enraging Sassoon even more. His outstanding bravery is only matched by his literary prowess in poetry.