Almost a century ago a man held a vision that humans, in time, could live as freely as the birds: they would have the means to travel the world at will, no longer confined to airports and roads.

This man, driven by his dream, began to develop this vision of a vehicle that could help a man achieve exactly that, to hop off the road at will, fly for as long as he pleases, and then, as deftly as a bird, swoop down and immerse itself into the traffic.

In order to achieve his desire, the man gathered all his inheritance, his money, and possessions, and despite the hardest of times when the Great Depression had hit the streets of Chicago, invested it in this dream of a vehicle that one day might be designed to fly, land, and drive. He called the concept an “Omni-Medium Transport.”

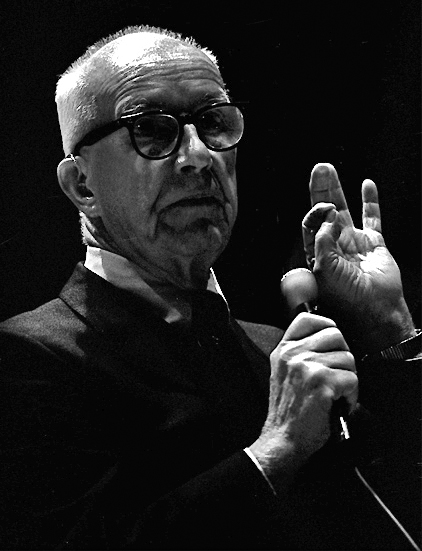

His name was Buckminster Fuller. The vehicle that he produced was labeled by the inventor himself a “zoom mobile.” It is now recognized as the Dymaxion car, the beautiful idea of a vehicle that unfortunately never came to fly the skies.

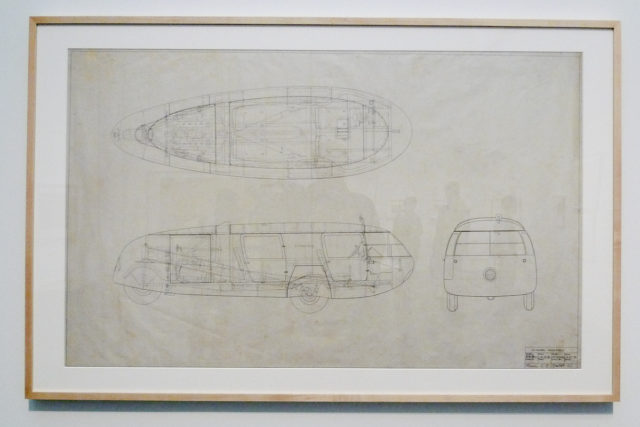

In 1930, the American designer, system theorist, and inventor born in Milton, Massachusetts, acquired the architectural magazine T-Square and rebranded it completely. Carrying the new name of Shelter, it was filled with content that Fuller, who was anonymously working as the editor of the new magazine, chose himself. After two years, he published sketches of his design of a land-air-water vehicle, the 4D Transport.

The name reflected Fuller’s vision that his vehicle would go beyond the ordinary. In physics and mathematics, a four-dimensional object transcends the traditional three dimensions of length. He believed that he was starting something that in the future would be redesigned and eventually built when scientific and engineering knowledge had evolved enough.

A wealthy businessman from Philadelphia named Philip Pearson wanting to invest in his project offered him $5,000, which translated would be around $91,000 today. The man was a former stockbroker, and concerned about potential profit motives and thinking the intention behind the offer was sinister, Fuller considered refusing it. However, the two of them met in person, and when Fuller saw that this stockbroker was almost as familiar with his field of study as he was, he accepted the offer. However, the contract they signed had a clause that would allow Fuller to invest the money in ice cream and sodas should he chose to do so, thus making the transaction more of a donation than an investment, and Fuller could go on with his research without outside pressure.

And so he did, setting up a workstation on the west side of the harbor in Bridgeport, Connecticut, in what was previously a dynamometer building of the defunct Locomobile Company at Tongue Point, in 1933. Here he launched the Dymaxion Corporation and hired the services of a naval architect named Starling Burgess, alongside 27 additional employees of whom most were former Rolls-Royce mechanics. They were 27 chosen from thousands who applied for the opened positions.

Months later and the company had created its first prototype and on Fuller’s own 38th birthday, July 12, 1933.

Fuller was aiming to realize his Omni Medium Transport vision, a vehicle that could go anywhere. In his view, the Dymaxion would ultimately have “wheels for ground travel and jet stilts for instant takeoff and flight.” The jet stilts were Fuller’s idea for a technology that, if developed sometime in the future, could provide compact and easy lift-off. This was 20 years before commercial jets came on to the market.

He knew that technology was not advanced to that level yet, so he focused on maybe the most dangerous and challenging part, landing and lifting on hard ground, a place where testing was more probable.

The vehicle was built as a front-wheel drive and the motor was placed at the rear end, designed in such a way that it would provide increased fuel efficiency while maintaining top speed.

The first prototype came out at 20 feet long, constructed as a joined two-frame chassis made of lightweight steel, with aircraft-type lightening holes. Beneath a front-wheel-drive layout, a Ford V8 engine producing 85 brake horsepower in the rear-engine was placed to power this extremely weird-looking vehicle, resembling a humpback whale.

Built as a roadster, the vehicle achieved a speed of 128 mph, Fuller said. Even before testing, the designer knew that the Dymaxion would have its limitations, which were later confirmed. The problematic aspect was the front, which started lifting from the road when driven at high speed, as well as proving to be very difficult to steer against the wind. Fuller knew the vehicle was not ready for public marketing and would need a professional driver to control it. For his vision to be complete, he had to wait for the technology to advance some more to allow him to continue, marking the vehicle an “idea in development,” instituting a program of constant refinement and improvement to the platform.

On October 27, 1933, the company made their first official launch in Chicago during Century of Progress World’s Fair. Unfortunately, right after the launch, the prototype crashed after being hit by another car driven by a Chicago South Park Commissioner, causing it to roll over and killing the Dymaxion’s driver, Francis T. Turner, a race-car driver from Birmingham, Alabama.

At first, nothing in the press mentioned that the accident had involved two cars. Instead, it was said that the crash was due to the Dymaxion’s unconventional configuration. Later reports after the investigation was completed confirmed that the Chicago politician’s car was swiftly and illegally removed from the scene of the accident before police had arrived. William Sempill, an aviation pioneer who was in the other car, testified that their vehicle came too close to the Dymaxion because the Commissioner had ordered the driver to get closer. He demand to get a better look at the strange vehicle. which had put everybody’s lives in danger.

Although not at fault, the bad publicity meant that the car never reached its potential, even though Fuller had made two additional prototypes. One of the three original prototypes survived through the ages, as well as two other semi-faithful replicas that were recently constructed. The Dymaxion was credited in the 2009 book Fifty Cars That Changed The World and was explored in the 2012 documentary The Last Dymaxion. Maybe it was a bad design, or maybe it was just a vision ahead of its time.