George R. R. Martin, in his epic Game of Thrones series, speaks of a holy place few dare to enter. The House of Black and White is a temple where men wear no faces and a girl has no name.

Little is known of this place, let alone of the people who reside in it. What is certain is that the House of Black and White sits alone on a small deserted island in the free city of Braavos and a secretive guild known only as the Faceless Men use it as a temple to worship the Many Faced God. And these men are both no one and anyone.

According to the lore, they are simultaneously a relief, an incredible expense for one willing to pay, and a swift death for the ones on the other side of the bargain. Their origin is believed to predate the founding of the city, with only legends mentioning men of the Valyrian Empire, slaves of the volcanic mines who freed themselves, set sail, and settled on a distant lagoon cloaked in fog, where they found the Secret City now known as Braavos. Residing there, these now highly trained assassins can also be viewed as protectors of the city and one of the greatest assets of the Iron Bank.

It has been suggested that the free city of Braavos is built on the idea of Renaissance Venice, a city in which a similar notorious group known as the Council of Ten operated for almost a 500 years, primarily tasked to search out and act on any suspected acts of treason against the Republic. It is almost inevitable, if you know of this time, to make the parallel. Both being secretive in their existence as well their actions, any resemblance between the two organizations is speculative, however.

From what evidence can be found, the movement began in 1310. After the unsuccessful conspiracy of Tiepolo, when Bajamonte Tiepolo (grandson of the former Doge Lorenzo Tiepolo) and Marco Querini, his fellow conspirator, tried to seize power over the Great Council and overthrow the Doge, Pietro Gradenigo, the Council of Ten, was formed as a special committee to stop further attempts even before they became a threat. They were given exceptional powers to act as prosecutors and met in absolute secrecy.

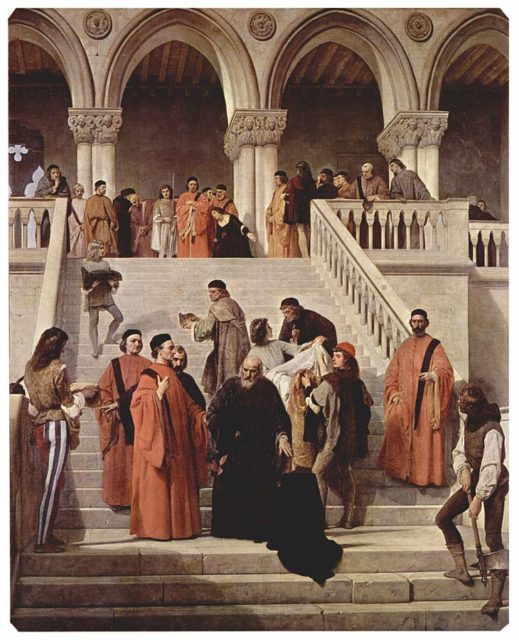

And so “The Ten,” formed at first as a part-time body and reelected every three months, became a permanent institution in 1355 after they successfully dealt with yet another attempted coup. This time it was instigated by Marino Faliero, the current Doge, who within months of his election tried a coup d’etat aiming to seize full power over the ruling aristocrats. Whether it was because they were poorly organized, or The Ten very effective, the coup was discovered and the Doge, after confessing his crimes, was beheaded and his body mutilated. As for his conspirators, 10 were arrested and hanged in front Palazzo Ducale in St Mark’s Square for everyone to see.

It was with this grotesque scenery staged right at the entrance of the city that the Council of Ten earned their terrifying reputation and their permanent place inside the government of the Venetian Republic, acting in extreme privacy as prosecutors, interrogators, and judiciaries in some cases for centuries to come.

During these years the Council, actually consisting of 17 members, including the Doge, formed a firm network of spies and informants through whom they managed to watch over everything from the state’s diplomacy and administration. In time, they managed to establish control over the secret police as well and came to know everything about everyone. They served as the last stance of justice, exercised in the most brutal of manners. If only the walls of the interrogation chambers inside the palace could speak about the screams of the sorrowful people tortured within.

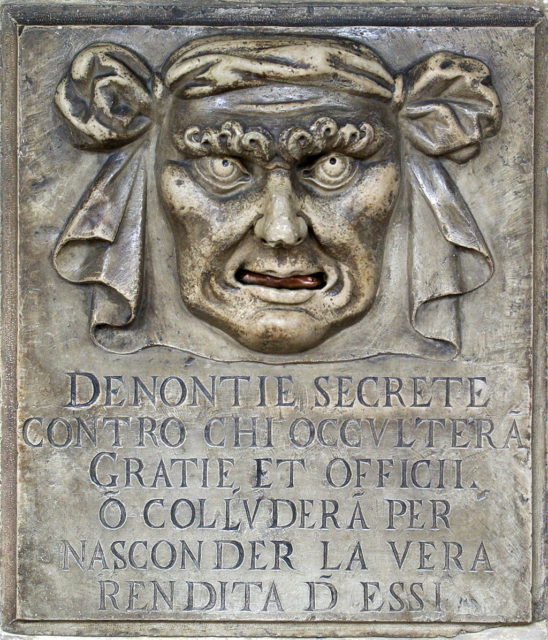

The official stance was that they were a vital organ needed for maintaining the stability of the Republic and preserving it from corrupt governance, yet many opposed this view, alleging the organization was nothing more than a prolonged arm of the wealthiest of people in Venice, giving power to a secretive group in order to protect themselves. However, during a time when everyone was always suspicious about everything, where “masked, faceless” men filled the streets of the city of spies and where it was dangerous to openly express one’s own opinion, few lived who voiced their dissent. Now only the Boche de leòn, or Lion’s Mouth, right at the top of the Giant’s Staircase in the palace where Marino Faliero was beheaded and where the Doges used to be crowned, serves as evidence of the Black Legend of Venice.

It is said that by 1457 the Council of Ten became the most powerful and feared institution in Venice and abroad. They had unlimited authority over all governmental affairs and soon enough found themselves with full control over the espionage and counterespionage services, which helped them to manage the military affairs of the Republic and its foreign policy.

In 1539 three new judiciaries were elected by the Council to serve as State Inquisitors and deal with the anonymous complaints filling “The Lion’s Mouth.” Their creation spurred the Black Legend of Venice and the story of the I tre babài, or The Three Boogymen, who roamed the streets cloaked in mantles. No man dared to look at them, let alone speak of them.

Granted supreme power, the inquisitors received the complaints, listened to the reports of their spies, and acted swiftly on them in a secret procedure. Amelot de la Houssaye, French translator of Tacitus, Machiavelli, and Sarpi in his book Histoire du govenrment de Venise (1676), one of the few writings that mention their existence, exposes their immense power, stating the inquisitors could order the drowning, poisoning or strangling og anyone plotting against the Republic, even the Doge himself. According to him, they had the authority and power to make servants kill their masters, have street children poison drinks, or pay spies to find out everything of noblemen and citizens, and not only in Venice for that matter. For them, no man was untouchable, not even kings or queens.

Mark Twain in his 1869 The Innocents Abroad, famously wrote about the state of affairs during those days: “If a man had an enemy in those old days, the cleverest thing he could do was to slip a note for the Council of Three into The Lion’s mouth, saying “This man is plotting against the Government.” If the awful Three found no proof, ten to one they would drown him anyhow, because he was a deep rascal since his plots were unsolvable. Masked judges and masked executioners, with unlimited power, and no appeal from their judgments, in that hard, cruel age, were not likely to be lenient with men they suspected yet could not convict.”

Hence, from the moment a white sheet of paper with a name in black letters engraved on it was dropped into the Lion’s Mouth, and then in the hands of “The Three,” in their special room under the roof painted by Veronese in the Doge’s Palace, the man named was already dead, one way or another. Just as the people whose names are spoken to the Faceless Men in the House of Black and White.

During their later stages of existence, it is believed the Council of Ten, as well as the three inquisitors, were also tasked to deal with debts owed to the banks of Venice. Consequently, they are alleged responsible for some disappearances and “accidental” deaths of noblemen and aristocrats throughout Europe, with people speaking of men dressed in clothes of peasants killing people in the street.

By doing so, they were no one and anyone if needed.