The serial killer called both “the .44. caliber killer” and “Son of Sam,” a 24-year-old postal worker named David Berkowitz, was the subject of the biggest police manhunt in the history of New York City. His string of nighttime shootings in 1976 and 1977, killing six young people and wounding seven others, came to an end after a parking ticket left on his car near a Brooklyn murder scene led police to his apartment building in Yonkers, just over the city line from the Bronx. On August 11, 1977, Berkowitz, after no more than 30 minutes of questioning, confessed to his crimes.

“Why? Why did you kill them?” a detective asked the suspect, according to a story that ran in The New York Times.

“It was a command,” Berkowitz responded. “I had a sign and I followed it. Sam told me what to do and I did it.”

Sam was a neighbor, he said, “who is really a man who lived 6,000 years ago,” and he gave Berkowitz orders through his dog. According to The New York Times, “Asked if he had any remorse, he reportedly said, ‘No, why should I?’ ”

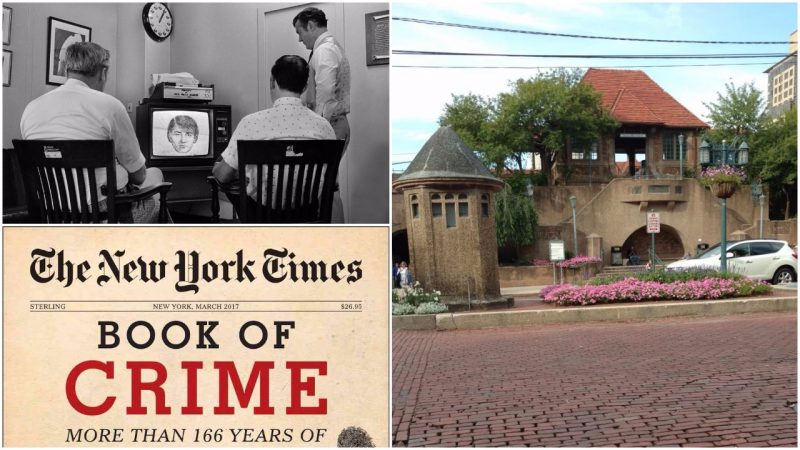

That day the citizens of the city Berkowitz had terrorized for a year got their first look at the murderer, pudgy-faced with glazed eyes and a fixed smile. “David had never been the focus of attraction in his life and now he was the center of attention for the whole world,” said Lawrence Klausner, author of a book on the serial killer.

Today New York City is considered one of the safest big cities in the United States, but 40 years ago it was a different story. Crippled by a financial crisis that in 1975 President Gerald Ford refused to solve with a federal—bail-out” Ford to City: Drop Dead,” screamed the New York Daily News—the city faced a rate of violent crime that was rising fast. Overwhelmed police were trying to solve more than 1,000 murders in 1976.

Within the context of this chaos, the shooting death of 18-year-old Donna Lauria and the wounding of her friend while they talked together in front of her house in the Bronx in July 1976, followed by the shooting of a young couple in Flushing, Queens, and then the serious wounding of two teenage women in Flushing in November, were not initially connected in the minds of the police. The victims had all been shot by a stranger, a young man who ran up to them in the street, seemingly coming out of nowhere, and fired a .44 caliber Bulldog Revolver, with large bullets causing horrific damage. It was not a common gun or bullet, yet the police thought the various attacks were probably connected to the mafia or drugs.

But when, at 1:40 AM on Jan. 30, 1977, a young engaged couple sitting in their car in Forest Hills Gardens, Queens, were shot by a man using a .44 caliber revolver, killing 26-year-old Christine Freund, the police realized the cases must be related.

Holding a press conference, a visibly upset Mayor Abe Beame said, “In the last few weeks, New Yorkers have been subjected to a series of criminal outrages that are unmatched in recent memory.”

That is the moment when the panic struck. New York City is a famously tough place–it’s Gotham, the city that never sleeps, if you can make it there, you can make it anywhere, etcetera. But the knowledge that a man was roaming in the darkness, looking for people to shoot (a victim pattern was emerging of young women with long dark hair), left millions of New Yorkers terrified.

A police task formed, as officers recruited psychiatrists to help them come up with a profile–was the killer a voyeur? An impotent woman hater? Did he follow a pattern of the moon? Seventy detectives worked the case fulltime starting in April 1977. Police volunteered to help on their days off. But there were no breaks, no real clues. Witness descriptions were no better than a man in his twenties of medium build. False leads poured into the police.

The media’s role in covering the crime took a new turn when New York Daily News columnist Jimmy Breslin received letters full of violent rants that began with “Hello from the gutters of N.Y.C.” and signed by “Son of Sam.” In a strange scrawl, the killer wrote, “Sam’s a thirsty lad and he won’t let me stop killing until he gets his fill of blood.”

“No One Is Safe!” shouted the front page of The New York Post.

Not everything that happened during this period was a nightmare in New York. Disco fever gripped the metropolis, from the celebrities (Bianca Jagger, Gloria Vanderbilt, Truman Capote, and many more) flooding Manhattan’s Studio 54 to the working-class youngsters hitting the dance floor in the outer boroughs, inspiring a magazine story that turned into the film Saturday Night Fever.

In the world of sports, a new manager for the New York Yankees, hot-tempered Billy Martin, had been hired by George Steinbrenner in 1975, turning the ragtag team into winners capable of going all the way: the World Series. Martin’s fights with Steinbrenner and Martin’s fights with his new star player, Reggie Jackson, made for diverting reading.

But in the summer of 1977, as if nerves weren’t frayed enough by the presence of a serial killer, the lights went out during a brutal heat wave. The electricity failed in most of the city during July 13 and 14. Looting and vandalism were widespread, with more than 3,700 people arrested. A study estimated the cost of damages at $300 million. The city seemed on the brink of madness.

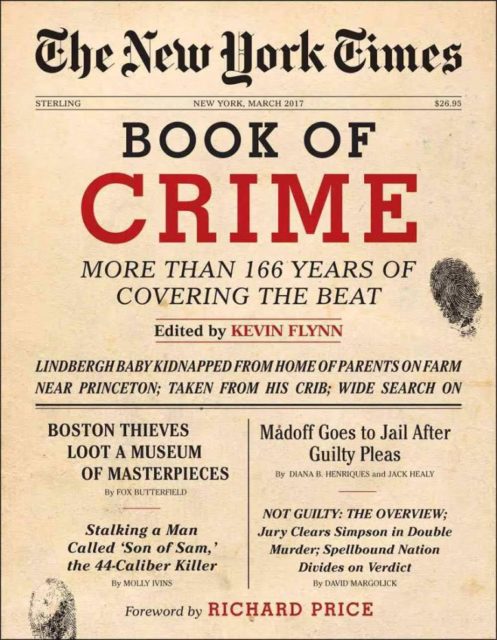

It was a time so troubled that almost 40 years later, when editor and investigative reporter Kevin Flynn of The New York Time, was putting together an anthology of the best crime reporting in the newspaper’s history for a book, the Son of Sam Murders was a special case. Flynn said in a recent interview, “When I picked for this book a story written after David Berkowitz was arrested, one of the editors here at the time made a strong case to me that we needed one written earlier too, because the latter story didn’t capture the terror that New York felt during the time when he was unidentified and Sam was out there killing people.” Book of Crime: More than 166 Years of Covering the Beat has two Son of Sam stories.

Despite the police task force’s round-the-clock efforts, Son of Sam struck again, and again. A 19-year-old was shot and killed in Queens on March 8 at 7:30 PM, walking home from a college class. On April 17 at 3 AM, a young couple sitting in a parked car on Hutchison River Parkway were shot dead. On June 26, another young couple were wounded, in Bayside, Queens.

Then, for the first time, the killer struck in the borough of Brooklyn. Robert Violante, 20 was shot in the head as he sat in a parked car with Stacy Moskowitz, 20, at 2:50 AM on July 31st. Moskowitz, also shot, did not survive her injuries.

However, a woman out that same night, on a walk near the murder scene, noticed a man tearing a ticket off the windshield of his car and throwing it on the ground. (The car was parked in front of a fire hydrant.) Once they learned the car owner’s identity, police went to Yonkers to question Berkowitz as a possible witness, but when they spotted weapons and strange letters in his Ford Galaxie car, they knew they had a suspect.

The police waited for him to go to his car, and when Berkowitz slid into the front seat, a triangular-shaped bag under his arm, Detective Sergeant William Gardella approached the car from the passenger side, shouting for Berkowitz to not move. The young man kept his fingers on the key in the ignition, turned very slowly to look at the officer and smiled, saying, “How come it took you so long?

Debate raged over whether Berkowitz was legally sane or not, but in the end, he pleaded guilty to the murders in court and is currently serving six consecutive 25-years-to-life sentences in a New York State prison. After being stabbed in prison and giving everyone around him a bad time—earning the nickname “—Berserkowitz” he was since become a born-again Christian and has said, “I continue to pray for the victims of my crimes.”

Berkowitz does not want to seek parole. According to the book Son of Sam: A Biography of David Berkowitz by Paul Brody, Berkowitz sent a letter to then-Governor George Pataki, saying, “Frankly, I can give you no good reason why I should even be considered for parole. I can, however, give you many reasons why I should not be.”