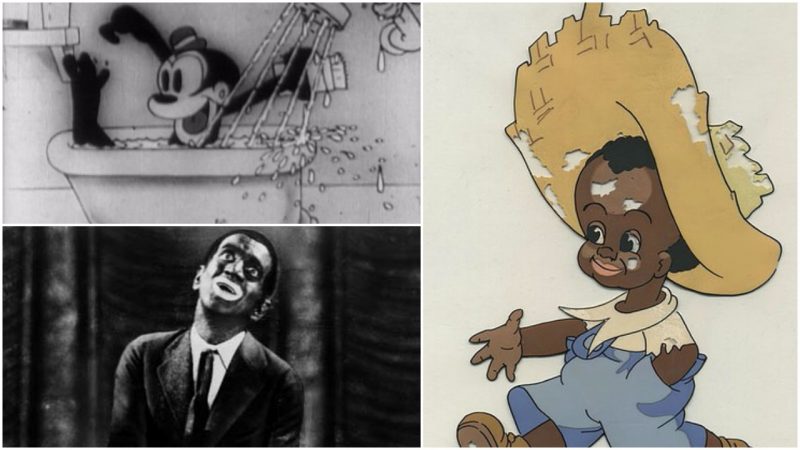

We all know the cartoon characters Daffy Duck, Porky Pig, Bugs Bunny, and Mickey Mouse. Aside from them, in the long history of cartoons there also frolicked some characters that were an innovation in the industry and popular in their time but now in the shadows of more famous ones. Bosko, the dancing and singing African American child, was one such character. He became one of the first animated characters that had a voice and entered into dialogues.

Bosko was created in 1927 by pioneering American animators Hugh Harman and Rudolf Ising. He was created because in those days there was a huge demand for “talking pictures.” Combining motion pictures with sound was a trend on the rise. People were amazed by this new technology and wanted more of it. Motivated by demand, Harman conceived the idea of Bosko, a singing character. He made the first drawings of his new cartoon hero in January 1928 and registered the character in the copyright office under the name of Bosko.

The pilot of the cartoon, titled Bosko, the Talk-Ink Kid, was done in 1929, in the style of Max Fleischer’s Out of the Inkwell cartoons. The pilot was very successful and showed Carl and Ising’s ability to animate a soundtrack and speech with dancing movements. It became the first cartoon that was made with a majority of synchronized speech. My Old Kentucky Home was the first cartoon with animated dialogue, but it only contained a small section of it. Harman and Ising’s cartoon was different because for the first time the focus was on dialogue instead of music.

The cartoon itself didn’t have any plot. It was focused on Bosko talking, singing, and dancing. It begins with camera footage of Ising working on a drawing table. Bosko is drawn on a piece of paper and comes alive. After he finishes his talking, singing, and dancing routine, Bosko is returned to the inkwell and the cartoon finishes.

After being shown to many different networks, the cartoon was bought by Warner Bros Pictures. Harman and Ising were asked to do a whole series of Bosko for Warner.

Leonard Michael Maltin, a prominent film critic, and historian, gives a very detailed picture of Bosko. According to him, Bosko was an animated version of a young African American, although he wasn’t based on a real person. Bosko’s companions were his girlfriend, Hony, and a dog called Bruno.

Bosko spoke in a Southern dialect. For example, whenever he was admiring something or enjoying something, Bosko used to say, “Mmmm! Dat sho’ is fine!” This expression became his catchphrase.

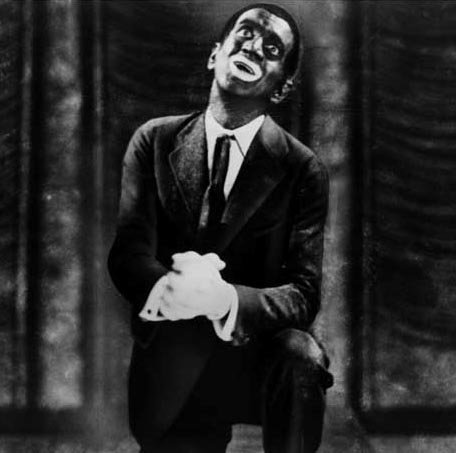

The character of Bosko was inspired and designed to resemble Al Jolson in The Jazz Singer (1927). Soon, Bosko became one of the most popular of the Looney Tunes characters. Bosko’s looks were based on Felix the Cat, but his attitude and personality were derived from the so-called “blackface” characters in the vaudeville and minstrel shows of the 1930s. It is important to note that these kinds of characters are today criticized as offensive to the African American community.

Bosko was good at singing, dancing, and playing instruments. He could play anything, even objects that were not intended as instruments.

In a way, Bosko and Honey were depicted as the opposites of Mickey and Minnie Mouse. They were placed in the same situations and given the same adventures, but they represented African Americans and in a fairly balanced manner. According to some critics, Bosko and Honey were the most “positive” representations of African Americans at the time. It is believed by animation historians that Harman and Ising weren’t concerned with Bosko’s race at all. They wanted to avoid stereotypes as much as they could, and therefore they represented Bosko as a resourceful young man. One exception is an episode called Congo Jazz (1930). Here, Bosko is placed between a chimpanzee and a gorilla drawn with similar faces like him. Nothing is different except Bosko’s clothes and size.

Bosko was a major hit during the 1930s. He starred in 39 animated musical cartoons. In these early years of sound animation, Bosko was viewed positively. People were amazed by him walking and dancing in the same rhythm as the music. Luckily for Harman and Ising, who previously worked for Disney and then quit, they were offered better conditions by Warner Bros. Through Warner Bros, they had access to a huge musical database and free access to sound design equipment. Disney, on the other hand, had to pay for all of this and mostly relied on public domain music.

Although they were very basic, Bosko’s cartoons were popular in those days and rivaled Mickey Mouse for a long time. Eventually, Disney would start making better cartoons, but Bosko will always be remembered as an innovation in animation as well as a step forward on the road to racial equality. Eventually, Bosko’s accent disappeared, and he became even more racially balanced.

After Warner Bros, Bosko was bought by MGM in 1933 and it was discontinued due to some negative reactions. Bosko was retired, and Harman and Ising were fired from MGM because of some cost overruns in their animations.