There may be something quite sinister behind Magritte’s reality-defying paintings. A feeling of uneasiness almost always accompanies the audience at a Magritte exhibition. Or maybe not. The great surrealist doesn’t mean to cause a disturbance. His peculiar approach to the canvas covers everything except the intent to frighten or confuse the viewer.

Still, the bowler-hatted men suspended in mid-air, the window-merging canvases, the outlandish dreamscapes, all continue to provoke deep thought. The painted conundrums never fail to invoke certain questions in every viewer with just a glance.

His hypnotizing works of art are always a confounding sight to behold, even for those familiar with his work. In the 21st century, audiences struggle with finding a true meaning in Magritte’s paintings, to no avail.

The Belgian painter is known for depicting ordinary objects in an unusual context. Through creating common images and placing them in extreme contexts, Magritte sought to have his viewers question the very ability of a painting to truly represent an ordinary object.

With that said, his work gracefully challenges the audience’s perceptions of reality and invokes playful skepticism when it comes to “finding meaning” in art. Magritte’s genius lies in his images’ resilience, which stubbornly defies a straightforward answer. He absolutely loathed having his work lifelessly psychoanalyzed and dissected for simple meanings.

Despite his unpopular first exhibition, the surrealist was met with great critical acclaim and popularity during his lifetime. His exhibitions were always widely attended and his influence is felt in every nook and cranny of modern culture and art. The Magritte Museum, which opened in 2009, displays about 200 of his paintings and sculptures.

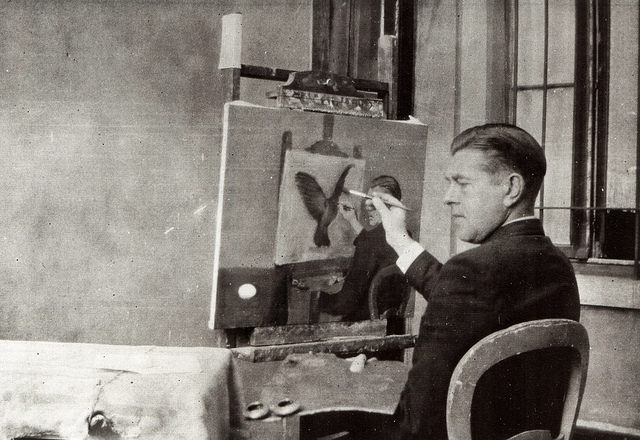

The oldest son of a wealthy tailor and textile merchant, Léopold Magritte, the Belgian-born artist began his drawing lessons at the age of 10 in the town of Lessines. As a child, he showed great interest in art but didn’t fully commit himself to it until after his time serving in the Belgian infantry.

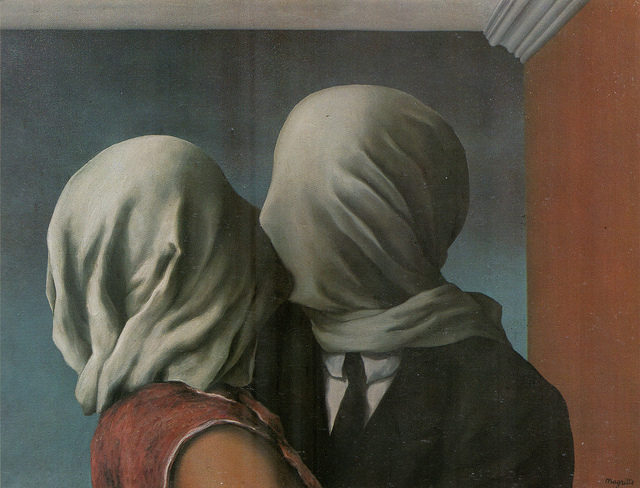

But the young aspiring artist had endured a terrible tragedy on March 12, 1912, when his mother drowned herself in the Sambre River. Four days later, the authorities dragged her body out of the water, and a 13-year-old Magritte witnessed it in horrific detail.

As the story goes, her wet dress was only covering her face instead of her body, which cemented a traumatic memory that is reflected in Magritte’s later paintings of people’s faces obscured with white cloth, as can be seen in his 1928 work The Lovers.

Magritte was also known to make advertising posters and forgeries of Chirico, Braque, and Picasso. He even went to extreme lengths such as printing money to survive in dire economic times. When World War II broke out, his reaction was his experimental Vache period, in which he depicted comically abstract images very different from his later work.

Although his art puzzles and unnerves the onlooker, what he really wanted was to cheer his audience. He wanted to calm the Belgian folk with color and goodwill during the harsh times of humanity. So he broke out of his traditional style of painting and went full on impressionist.

Even though his first exhibition of the Vache period was poorly received, he became well known for many witty and thought-provoking paintings later on. He wasn’t favored much by Breton and his circle of pompous surrealists, but he was nevertheless a prominent pillar of surrealism itself.

Artist Ed Ruscha met Magritte in 1967, a coincidental encounter in Venice. He speaks in an interview for a contemporary art magazine about Magritte’s down-to-earth personality amidst the period of his great popularity: “His demeanor was that of a total gentleman, a kindly man, and that was really impressive to me, knowing this man’s work.”

Magritte’s moment of epiphany was when he first saw Chirico’s Love Song, a true masterpiece by the Italian genius. With this work, Chirico managed to join the artificial with the organic, layering new backgrounds of mystery.

It was precisely that exact same mystery, that sense of wonder, which separated the Belgian painter from his surrealist contemporaries. Joan Miro was known for his “automatic” approach, allowing his own unconscious to control the brush, and Dali kept depicting dreamscapes while trying to give an explanation to their logic, but Magritte managed to intermesh and juxtapose reality itself, zig-zagging his way out of conventional perception.

There really is nothing to it. There are no life-changing ideas hiding under the layers of color. The 20th-century surrealists knew this. Armed only with humor in their art and a desire to surprise through playful channeling, the movement did all it could to project and mark a post-war period all by itself.

Unfortunately, that same playfulness has a chance to backfire miserably. When there is no threshold, no indicator to tell the emphasis and context of the compositions, nobody would know whether or not to take them seriously. What does the artist truly intend? How can one distinguish the message from a static puzzle of meaningless context?

He may invoke floods of confusion, only, unlike most of the uptight surrealist killjoys, Magritte doesn’t “scream” in your face with God-forsaken geometries. He merely gives you directions. He doesn’t cram ideologies in your head–he’s on your side. An eccentric friend who laughs with you, not at you.

Additionally, his tidy, neutral style in which he decides the reality breach is greatly appealing to the general public. It gracefully pleases the most conservative observer, soothing his nerves with smooth texture and mellow color.

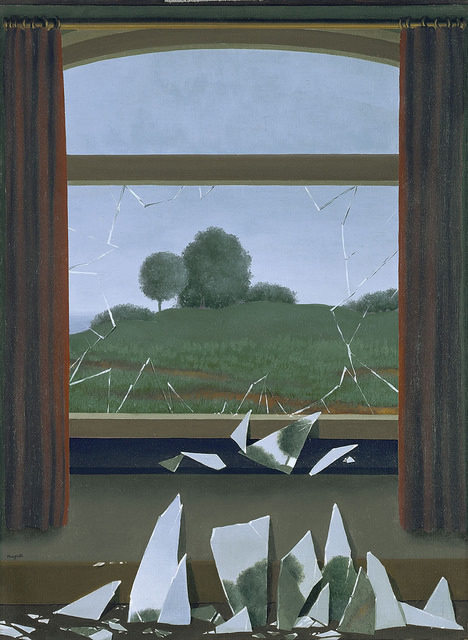

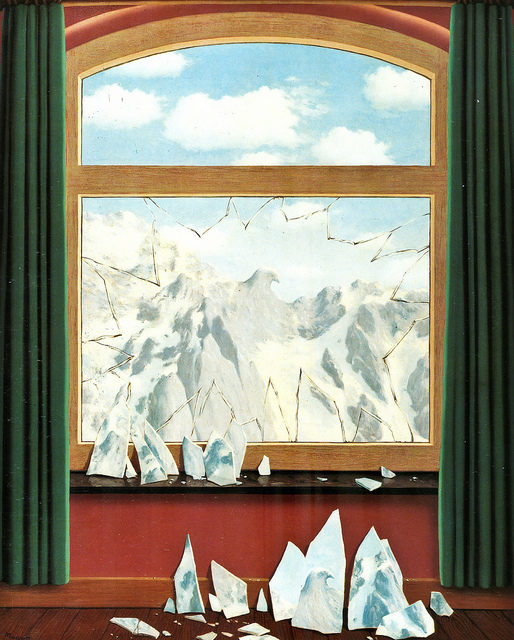

His deadpan neutral style garnered popularity then and still goes strong. But the same popularity gained from it shrouded the bigger picture of Magritte’s message about the unknowable, the universal mystery which is impossible to solve, and the vulnerable, shatter-glass human perception.

“I want to create a mystery, not to solve it,” Magritte once famously said. The paintings are not described as deadpan by accident. If one can drop the analysis for just one moment and stop and enjoy the joke behind it all, then Magritte’s job is done.

His paintings are clearly supported by the endless pillars of comedy, holding everything in place from within. Magritte swaps regular objects in a given background, doing everything he can to challenge the average man’s cemented perception and give out the message that this should not be taken so seriously.

A man looking at a mirror with his reflection showing the back of his head, lamps lighting up the street in the middle of day, an apple in front of a man’s face, a tree with clouds for branches. The artworks trigger the same way jokes and punchlines do, a simple mathematical function like multiplication, negation, or reversal, almost as if there is a pattern.

But that’s the deal with Magritte, there is no pattern. He keeps finding out funny ways to shatter every little piece of reasoning you have for his universe. A reality with the intricate mesh of context and object in which the “Magrittian logic” somehow still stands intact within the confines of that exact universe.

Simply put, he paints jokes. Almost in a farcical way, as if he is endlessly playing with reality and illusions in an effort to break any assumptions about the solidity of objects and, in Magritte’s case, to arouse skepticism, to make everyone question everything.

“He is so firmly lodged in my brain that frequently I’ll see something and think, ‘Oh, that’s a bit Magrittean,’ “ says Terry Gilliam. The Monty Python legend is a fan of Magritte, whose work can be noted as an influence. One can easily imagine Cleese in a bowler hat.

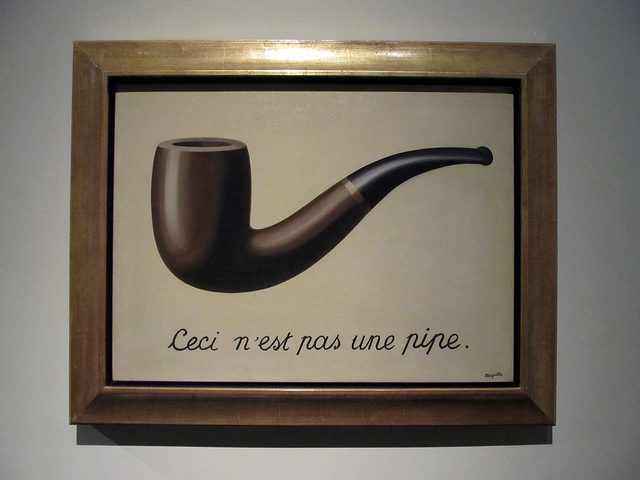

The Treachery of Images is a fine example of his comical method, and additionally, his most famous work. The words “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” are written just under a picture of a pipe. Hilarious.

Amusingly enough, it resembles a basic structure for a joke. A self-defeating prophecy, deconstructing its only purpose as a message. Even if there ever were a deeper narrative here, we could only hope that it could be somehow understood under the magnifying glass of general logic.

It may seem a simple contradiction, after all. But it really is true. It’s not a pipe, it’s an image of a pipe. “Of course it’s not a pipe. Just try to fill it with tobacco.” That was his answer when Magritte was asked about this bizarre masterpiece.

Still, the logic of it all hides just under the layers of the comical absurd, with its integrity intact, despite the depiction of absolute discord of reality and its unpredictable effect on human perception. “Visible things always hide other visible things,” Magritte would argue.

He sets a basis of a recognizable universe, devoid from any cultural, religious, or political, and subtly distorts its fundamental premise. Thus creating distorted landscapes and portraits that somehow reflect the essence of the real world.

The living rooms, the light posts, skies, the common bowler-hatted men, the famous apples, all are objects of true neutrality. They are a universal artistic dictionary that defies time and this may be why his artwork is still relevant today, if not more.

As layers upon layers fold and unfold at the same time, almost as if they’re in a quantum state of uncertainty, Magritte manages to depict multiple sequences of intermeshed realities. If this is just scratching the surface of Magritte’s artwork, one could only imagine what hides behind the absurdities.

Something exists, and after a while, it ceases to exist. Perhaps that is an important fragment of Magritte’s message he is trying so desperately to send. Our perception doesn’t tell us if the world that surrounds us will still be here after we are no more.

Of course, paradoxical thematics were a staple of Surrealism and not only did Magritte dabble in this, he lived it thoroughly. He was undoubtedly a fine example of the well-respected bourgeoisie class, while at the same time he lived to destabilize the same bourgeoisie values and ideas.

“They want to revolutionize art, I wanted to break free from it,” he later said of young artists. The enthusiastic Magritte tried all sorts of experiments with perception in his art, from cubism, Dadaism, the notion of the absurd, and the inevitable human alienation of Existentialism. “We must not fear daylight just because it almost always illuminates a miserable world” he once said.

Paving a way for new ideas. He’s literally everywhere, the Apple company logo, the CBS’s eye logo, the reverse mirror gag, the bowler-hatted men, he’s so influential that we, the younger generation, don’t actually see much of the cultural dichotomy.

One cannot emphasize enough the influence Magritte had throughout the world from the 1940s until this day, along with other great thinkers like Dali and Picasso. What he did for the painters of the future was free up the already overcrowded room of conventional artistic understanding, not by cracking open a window, or opening a door, but simply enlarging the room itself in a Magrittian manner, with the walls and windows merging with the outside view and all.