For most people in positions of power, the easiest way out in times of trouble and tragedy is to save their own skin. Those who are willing to risk their careers and even their lives have always been rare. Nevertheless, people with hearts full of kindness and compassion have always existed, and it only takes one of these people to undo evil.

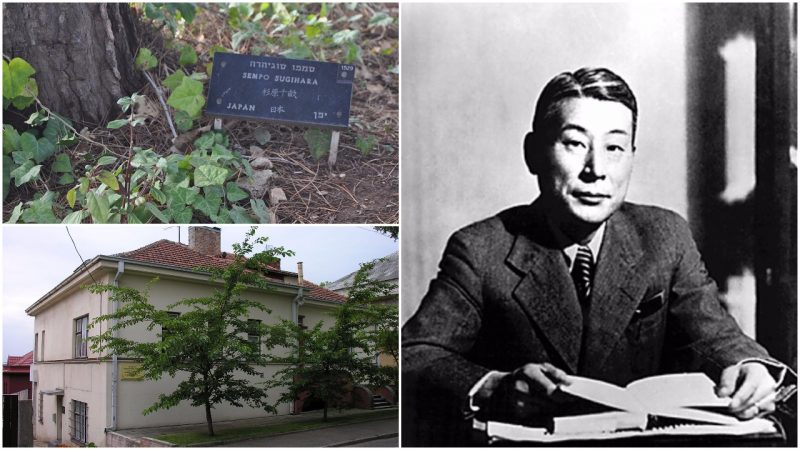

One such person was Chiune Sugihara, a Japanese diplomat in the Japanese Consulate in Kaunas, Lithuania, during World War II. We all know about Schindler and his dedication to saving as many Jewish lives as he could during the Holocaust, but not a lot is known about Sugihara, the “Japanese Schindler,” who saved the second largest number of people during the war. This is his story.

In 1939, Sugihara, who had previously served as a diplomat and was well versed in the Russian language and Soviet politics, was given the position of vice-consul of the Japanese Consulate in Kaunas. During this time, on the brink of WWII, Sugihara’s primary task was to obtain information about the Soviet and German troop deployments on the borders. He was supposed to determine if Germany was going to attack the Soviet Union.

Soon after, in 1940, the Soviets entered the territory of Lithuania and occupied it. This opened the doors for many Jewish refugees from Nazi-occupied Poland to seek shelter in Lithuania. At the same time, Lithuanian Jews desperately sought exit visas, but no one was willing to give them out. The situation was tense, and Kaunas became crowded with refugees.

In only a few months, the crisis came to Sugihara’s doors. One late July morning in 1940, Sugihara opened his front door to be greeted by a large group of desperate Polish Jews. With the Nazis approaching Lithuania, the people knew their destiny and believed that their only way out was heading east. They begged Sugihara to help them by giving them Japanese transit visas. If they had the Japanese visa, it would be easy for them to get the Soviet Union exit visa and flee to safety.

Sempo (as people in Lithuania used to call Sugihara), who was a man of principles, couldn’t promise them anything until he asked his superiors. He immediately sent a telegram to Japan asking for permission for visa issuing, only to be denied. He asked the Japanese Foreign Ministry three times, and he received a negative response.

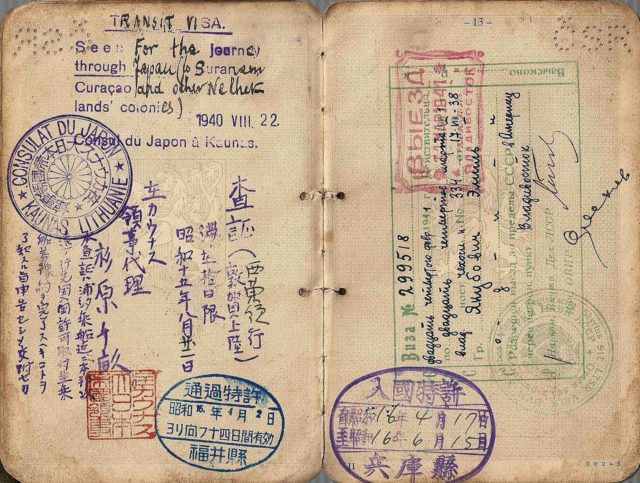

Time was passing and the situation was getting dire. Sempo couldn’t sleep peacefully knowing that people were going to die. From July 18 to August 28, 1940, Sugihara decided to act on his own, against the orders of the officials of his country who were completely ignorant of the whole situation. He took blank visa forms and started issuing 10-day transit visas through Japan for the Jews in Lithuania. Sempo also contacted Soviet Union representatives who promised to let the people with Japanese visas use the Trans-Siberian Railway (but at five times the usual ticket price) to reach Japan.

Sugihara continued producing Visas every day, and amazingly his superiors didn’t notice at the beginning. Some sources say that he used to handwrite a month’s worth of visas every day, working on this humanitarian “mission” up to 20 hours each day. Sempo painstakingly signed and wrote visas until September 4, when he was forced to leave the consulate as it was shutting down at the time. Even this didn’t stop Sempo. Some of those who knew him, and saw him leaving Kaunas, witnessed him writing visas on the way from his hotel to the train station. Even at the train station while he was boarding the train, Sugihara was rushing completed visa forms to the people. As a final act of kindness, Sempo put aside blank sheets of paper carrying the official consulate seal and his signature, which were later used for making fake visas by the refugees.

As the train prepared to leave the station, Sempo stood in front of the crowd of refugees gathered around the train and apologized because he wasn’t able to help them anymore. Filled with sadness, he bowed to the refugees, and they waved him goodbye with kindest wishes and a promise that he would meet them again in the future.

This terrible war that caused great suffering and incredibly high numbers of lost lives came to an end. Millions of people died either in combat or in the concentration camps. Fortunately, even during that time of horror, people such as Sempo managed to save thousands of lives and secure a future for the following generations. There are various estimations about the number of lives Sugihara managed to save with his “visas for life,” but most experts agree that he saved around 10,000 lives. Because of his work, more than 40,000 descendants of those that he saved are alive today.

After the Japanese Consulate in Kaunas was closed, Sempo was reassigned to Königsberg and following that he was made a Consul General in Prague, and lastly in Bucharest from 1942 to 1944. Through all this time, his superiors never forgot that he went against their orders. The war was coming to an end, and the Soviets entered Romania, where Sempo was serving at the time. He was captured and sent to a prisoner of war camp, together with his family. They were kept imprisoned for 18 months. In 1947, one year after his release, Sempo returned home and was asked to resign, allegedly due to cutbacks in the ministry, but his close friends said that he was removed because of the “Lithuania incident.”

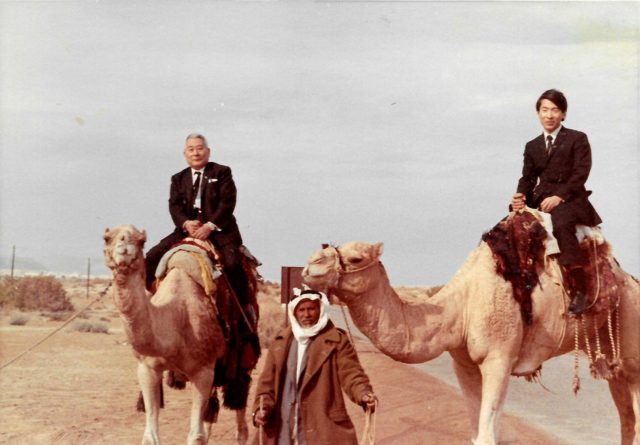

Sugihara’s diplomatic career ended, and he moved to Fujisawa in the Kanagawa prefecture of Japan. There he was forced to do all kinds of jobs to feed his three sons and wife. As people say, “all good deeds are ultimately rewarded.” Jehoshua Nishri, one of those that Sempo saved, became an attache in the Israeli Embassy in Tokyo. In 1968, Nishri managed to find Sugihara and in the following year, he took him to Israel where he was welcomed with the highest state honors.

In 1985, with the help of those saved by his great humanitarian work, Sugihara was granted the title of “Righteous Among the Nations.” He became the only Japanese citizen to ever be given this honor. When asked why he began issuing visas to the refugees against his government’s wishes, Sugihara replied that they were human beings in desperate need of help and that it is an obligation of every human being to help those in need.

Unfortunately, Chiune Sugihara died one year after he was given his recognition. Those who help the most usually keep out of the eyes of the public, and so it was that Sugihara remained virtually unknown to the world and those in his country. Only when he died and when a huge delegation from across the world came to his final farewell, did people realize how important he was.

May he rest in peace and also may he be an example to all of those who are in a position where they can help people in need. Sometimes it is worth going against the system when lives are at stake. Lives are sacred, and we all need to help when we can.