Located approximately 5 kilometers to the northwest of Persepolis, the capital of the ancient Persian Empire, Naqsh-e Rustam (meaning Throne of Rustam) is an ancient necropolis for four Achaemenid rulers and their families from the fifth and fourth centuries BCE. In addition to being a royal necropolis, Naqsh-e Rustam became a major center of sacrifice and celebration for the Sasanians between the third and seventh century CE.

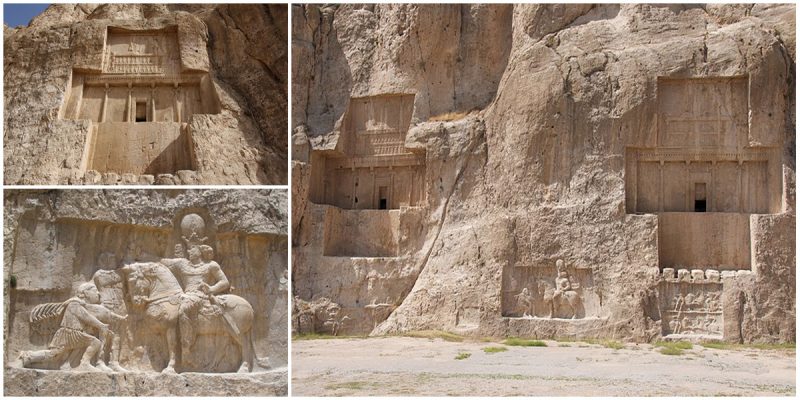

The tombs belong to Achaemenid kings and are known locally as the ‘Persian crosses’, due to the façade of the tombs, which resembles a cross. The entrance to each tomb is at the center of each cross, which opens onto to a small chamber, where the king lay in a sarcophagus. The horizontal beam of each of the tomb’s facades is believed to be a replica of the entrance of the palace at Persepolis.

Carved side-by-side into the hill rock, the facades of the cruciform tombs resemble the living quarters of the palaces at Persepolis.

Although there are four tombs, only one of them, the oldest, can be positively identified as the tomb of Darius I the Great (c. 522-486 BC), the third ruler of the Achaemenid Empire. The facade contains inscribed text and the engraved panel that forms the top arm of the cross shaped façade contains an image of Darius standing in prayer before a fire altar.

Later, three similar royal rock tombs were added and they are believed to belong to Darius’ successors, Xerxes I (c. 486-465 BC), Artaxerxes I Makrocheir (c. 465-424 BC) and Darius II (c. 423-404 BC).

It is believed that all the tombs were looted and desecrated following the invasion of the Achaemenid empire by Alexander the Great during the 4th century BC.

One of the mysteries of the site is the purpose of the Kabah-i Zardusht (translated as the Cube or Enclosure of Zarathustra). It is a rectangular stone tower, mostly solid except for a small room at the top that faces the cliffside, set roughly in front of tomb number four (the westernmost Achaemenid-era tomb). Various interpretations have been proposed for its purpose – a royal treasury, a tomb, a fire temple, or even an astronomical observatory and calendar.

Today, Naqsh-e Rustam stands as a lasting memory of a once powerful empire that ruled over a significant portion of the ancient world.