In recent years, some striking portrayals of famous historical figures, from Dante Alighieri to Queen Nefertiti, have been presented as 3D facial reconstructions. But perhaps even more interesting is the facial reconstruction of a Scottish woman, accused of witchcraft some 313 years ago.

Her name was Lilias Adie, a woman probably in her sixties and a resident of the Scottish village of Torryburn. As the local legends have it, in 1704 one of her neighbors accused Lilias of plotting something wicked and harmful, and as you might have guessed, it was a time when witch hunting was at its peak. After the elderly woman was accused, she was imprisoned, interrogated, and tortured into admitting that she had been “intimate” with the devil.

Shortly after the confession, Lilias passed away while still imprisoned, and so locals couldn’t “properly” burn her, as was the fate of most alleged witches for their wrongdoings. One theory suggests that she may have even taken her life, to avoid that fiery fate.

Fast-forward three centuries: the face of Lilias Adie underwent digital reconstruction, and the final version was presented on BBC Radio Scotland’s Time Travel program, for a special edition airing on Halloween day, 2017.

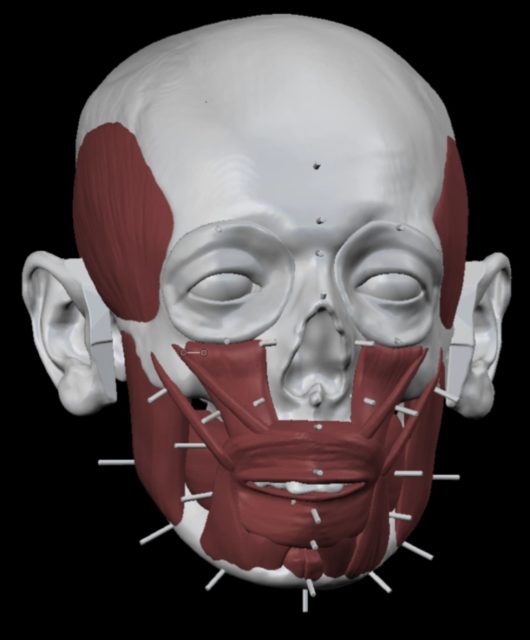

According to representatives of the University of Dundee, the forensic experts used photographic material depicting her skull to reconstruct the face. The photographic material had previously been safely stored at the St. Andrews University Museum in Scotland, but the skull was reportedly lost at some point during the 20th century.

This way, the reconstruction, as experts commented, is based on the resemblance of what a Scottish face might have looked like back then and so can only be as accurate as what we assume that to be. Because most witches met their fates at the stake, there’s little hope of a more objective reconstruction based on a real skull could ever be accomplished.

“It was a truly eerie moment when the face of Lilias suddenly appeared. Here was the face of a woman you could have a chat with, though knowing her story it was a wee bit difficult to look her in the eye,” stated Susan Morrison as she presented the authentic digital reconstruction.

Dr. Christopher Rynn, who conducted the process of 3D virtual sculpturing, remarked,“There was nothing in Lilias’ story that suggested to me that nowadays she would be considered as anything other than a victim of horrible circumstances, so I saw no reason to pull the face into an unpleasant or mean expression and she ended up having quite a kind face, quite naturally.”

After she died, Lilias’ body was buried on a beach and a large stone was placed to guard her grave. Burying her this way suggests that the local people had fears that she might return–that the devil had powers to resurrect the dead.

However, the beach didn’t make for a place where Ms. Aide could rest in peace forever. During the 19th century, her remains were dug up for scientific purposes, after which her skull was sent to St. Andrews University Museum. There, it was photographed before mysteriously going missing, and it was these photos which have made possible the recent digital reconstruction. The skull is indeed gone, but luckily the photographs have remained, having been archived at the National Library of Scotland.

What is known about the elderly lady is that she might have been fragile and sick in the final years of her life. She had entered her seventh decade and naturally, her eyesight was diminishing. More records tell that she didn’t reveal any names of other “witches,” something that was certainly demanded of her while she was undergoing interrogation and torture, as was the purpose of such sessions.

Or as program historian Louise Yoeman has commented, “Lilias said that she couldn’t give the names of other women at the witches’ gatherings as they were masked like gentlewomen.” Instead, she had only mentioned names of women who were already associated with witchcraft, so she was creative in protecting any other possible innocent victims who might have followed the same ghastly fate as she did.

It is believed that up to 60,000 people, a vast majority of whom were women who had been accused of witchcraft were burned or otherwise executed around Europe and the American colonies from the 15th up to the 18th century. Lilias Adie is the name of only one of whose life was lost for all the wrong reasons.