You don’t have to be a history buff to know that D-Day was the start of Operation Overlord–at the time, the biggest invasion in history and undoubtedly the most significant Allied victory in World War II.

It was June 6, 1944, when 160,000 American, British, Canadian, and Free French troops landed on the shores of Normandy, France, and marked the beginning of the end of World War II.

Although by the year 1943 the Allies had won most of the battles in Africa, and by September 8, 1943, Italy had surrendered unconditionally, the end of the Second World War was not even close. The Allies now set their eyes on Nazi-occupied Europe and began planning their next move, which included a large-scale invasion of the Old Continent. Many locations were previously considered as sites of the invasion, including the port cities of Cherbourg and Le Havre, but it was eventually decided that the definitive site of the invasion would be Normandy. According to the masterminds of the invasion, this region was more than suitable for an amphibious operation.

It was clear that the invasion plan would require consideration of many factors and details. From pre-invasion training of the troops to mass production of weapons and supplies, the Allies had planned everything, including the much needed artificial harbors along the coast of Normandy. The lack of ports was probably one of the main reasons why German commanders didn’t consider Normandy as a possible invasion site.

Soldiers, Sailors, and Airmen of the Allied Expeditionary Force!

You are about to embark upon the Great Crusade, toward which we have striven these many months. The eyes of the world are upon you. The hopes and prayers of liberty-loving people everywhere march with you. In company with our brave Allies and brothers-in-arms on other Fronts, you will bring about the destruction of the German war machine, the elimination of Nazi tyranny over the oppressed peoples of Europe, and security for ourselves in a free world.

This is the beginning of the letter that General Eisenhower, commander of all Allied forces in Europe, sent to the troops prior to the invasion of Normandy. His words were not just meant to boost the morale of the soldiers, but they clearly summed up the exceptional significance of the operation that was about to begin.

It’s been more than 70 years since General Dwight D. Eisenhower launched Operation Overlord, and it seems that we have all the information about D-Day available on the internet, just like we have the latest news from any part of the world. But how did the American people learn of the invasion in an era without internet?

When people of New York woke up on the morning of June 6, 1944, they could hear some short official statements on the radio and read some of the headlines in the newspapers, but there weren’t any details of where their sons, fathers, and brothers had landed.

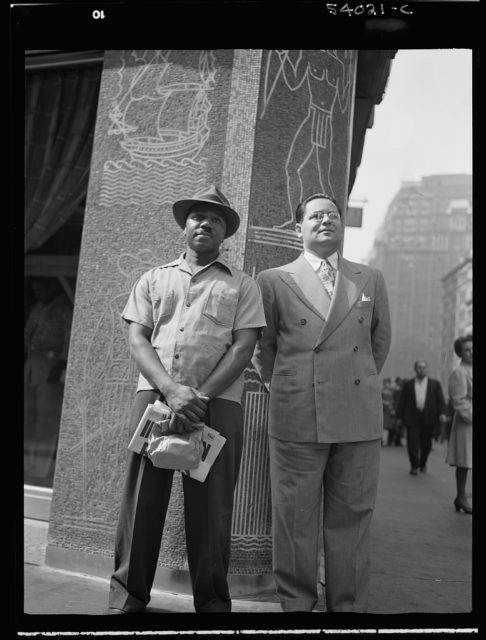

There weren’t any live radio reports from the shores of Normandy and the only way the Americans in New York could get news about D-Day was going to Times Square, where the electronic news sign on the Times building provided the latest news about the invasion.

These are some of the photographs taken on D-Day in New York, and they show people gathered in front of the Times Square building, reading the news about the invasion and patiently waiting for the latest details to be written.

The day when the Allied troops landed on the shores of Normandy is undoubtedly the crucial turning point in World War II. The operation was successful, and over 170,000 soldiers successfully stormed the beaches of Normandy that day.

In less than three months, the Allies liberated all of northern France and on May 8, 1945, 11 months after D-Day, Germany’s Field Marshall Wilhelm Keitel signed the final surrender terms in Berlin.