Before the Civil War, when you died in the U.S., your body would be laid out on a table in the parlor (if you had one), on a bed (if you had a spare), or in the kitchen (pity the cook). The body would be washed and dressed, but maybe not in the finest, as those were useful garments and times were tough. Candles might surround the body to mask the smell.

During the next few days, family and friends would come by to pay respects. The local carpenter would hammer together a simple pine casket (if you could afford such luxury) and your body buried in a small plot, likely with other predeceased family members, typically near woods, possibly beside a house of worship.

The Civil War changed all that. After historically bloody battles, there were too many bodies strewn over fields and hills to bury. Some were left where they fell, others rolled into trenches or mass graves. A few wealthy Northern families attempted to retrieve their fallen brethren, but lack of refrigeration made this often an impractical and messy business. Southern heat and humidity sped decomposition; buzzards and maggots quickly swooped in; an unbearable stench wafted for miles.

Ancient Egyptians, of course, had their own centuries-old techniques for dealing with the dead, mummifying the bodies by removing all the internal organs, filling the cavity, and wrapping it in shrouds. In other ancient cultures, to minimize effects of decay for days of ritualized mourning, bodies had been essentially pickled in vinegar, honey, or wine.

The modern practice of embalming gained strength in the mid-1800s. In 1838, a Frenchman published Histoire des Embaumements, describing a process that removed blood from the body and injected veins with a preservative, according to Smithsonian magazine. The book was translated into English and reached American shores in the early 1840s. Arsenic, mercury, and formaldehyde were common first preservatives used in the U.S.

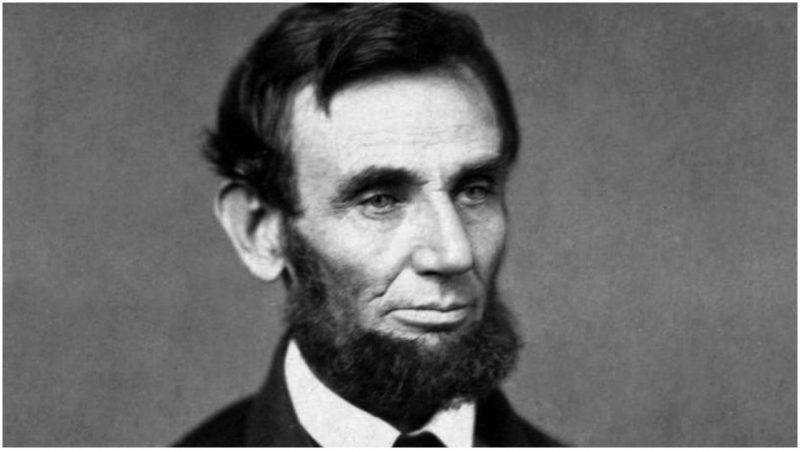

Embalming gained notoriety after the death of the first Union soldier in the Civil War. Army Medical Corps Colonel Elmore Ellsworth was shot removing a Confederate flag from a Virginia rooftop. Thomas Holmes, a pioneer in the industry who experimented with preservatives while working as a coroner’s assistant, offered his services to the family. Colonel Ellsworth’s body was laid in state at the White House per the request of his friend President Abraham Lincoln, who took note of the embalmment, and it was then taken by train to New York City, to be viewed by thousands.

News of embalming preservation spread quickly. Enterprising men followed Union and Confederate soldiers, pitched tents near battlefields for “field embalmings,” and offered soldiers the chance to pre-pay $100 embalmments should they be killed in battle. Smithsonian reports that out of an estimated 600,000 dead in the war, as many as 40,000 were embalmed. General Ulysses S. Grant had to order the opportunistic embalmers to stay behind battle lines, as they were negatively impacting morale.

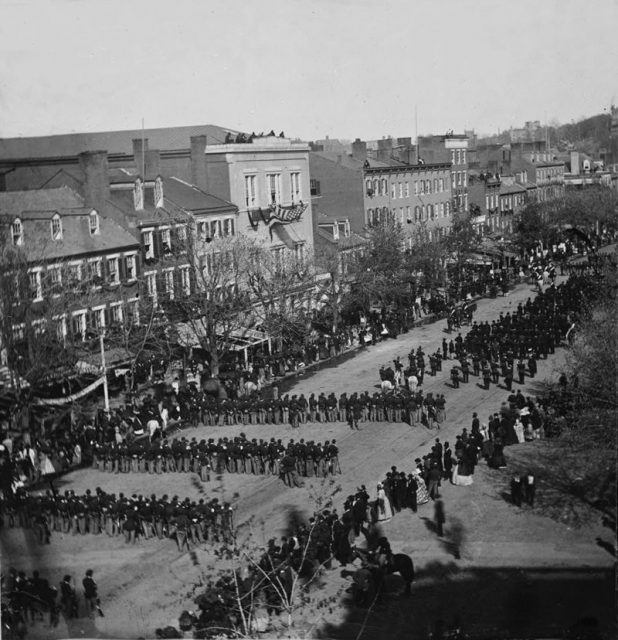

In 1862, when President Lincoln’s 11-year-old son died of typhoid, his grief-stricken father had the body embalmed by Henry P. Cattell, who would later handle the president’s own body. After Lincoln’s assassination in 1865, the president was taken by train on a journey from Washington, D.C., to Springfield, Illinois, where he and his disinterred son would be laid to rest.

Lincoln’s funeral procession made 11 stops along the way so that the public could see his body. Hundreds of thousands of people lined up to pay respects; newspapers reported on the funeral parade. That he appeared life-like had the effect of acceptance spreading for the embalming practice. Cattell traveled with the funeral party, according to Mental Floss, giving Lincoln “touchups” along the way.

Today, the U.S. has the most robust funeral industry and leads the world in embalming. For practical and religious reasons, other countries have different rituals. In Japan, a small country with overcrowded cemeteries, everyone is cremated. Muslim and Jewish traditions call for burial within 24 hours.

Mongolians and Tibetans are famous for sky burials, where bodies are left to the elements at high altitudes. In Germany, strict laws require burial, whether the body has been cremated or not, making it nearly the most expensive place on Earth to pass away.