During the 1830s, New York City was a city in the midst of rapid development. As such, it experienced serious growing pains, and one of them was the number of homeless children. A statistic from 1850 shows that during that year, there were around 20,000 to 30,000 homeless children in New York City alone, at a time when the total population of the city was merely 500,000. Many other larger cities on the East Coast had the same issue and something needed to be done. This is when a young Methodist priest named Charles Loring Brace put into motion the idea of what would later become known as the “Orphan Train Movement,” a proto-welfare program that moved orphans and homeless children from the cities of the East to the small towns and rural areas of the Midwest.

Life was not easy for homeless children at the middle of the 1800s. Many of the children became orphans after their parents died as the result of epidemics such as typhoid, yellow fever, or flu. Some of those who still had parents were left on their own because of poverty, a variety of illnesses, or the addictions of their parents. To survive the harsh conditions on the streets, these children (they were called “street Arabs”) did all sorts of things: they organized themselves into gangs for protection and many of them stole, while others sold matches, newspapers, or rags.

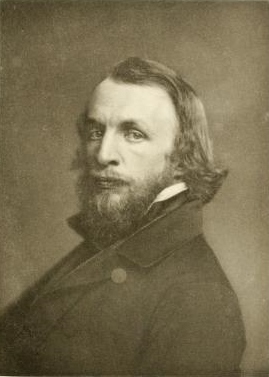

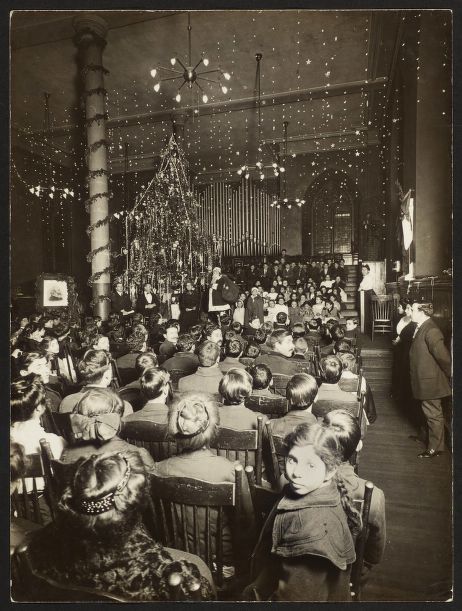

It was 1853 when some people decided to do something to protect these children. The most vocal on this issue was Charles Loring Brace. Concerned for the future of the orphans and homeless children, Brace opened a foundation called the Children’s Aid Society. Its goal was to help orphans and destitute children get a better life. At the beginning, the Society offered only religious lectures and basic education. After a while, the group opened the first runaway shelter in the United States (the Newsboys’ Lodging House). Here young boys could get cheap accommodation and receive some education.

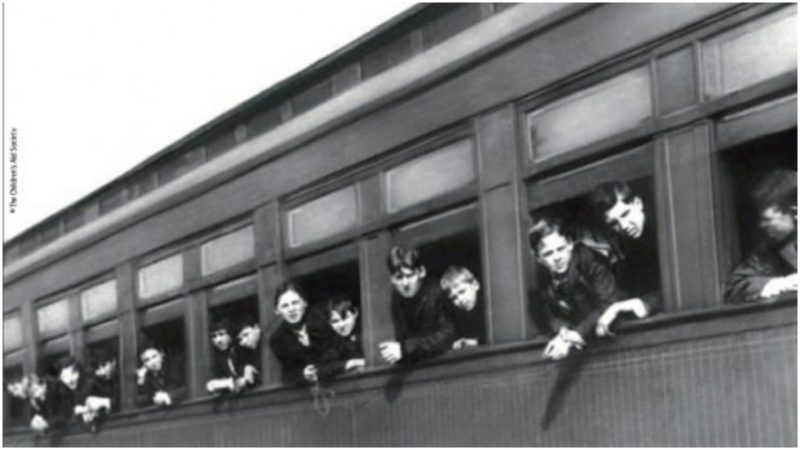

Brace’s organization tried to secure a job and a good home for every child, but soon his small crew wasn’t able to handle the huge numbers of children coming through the doors of the shelter. Something else needed to be done. Then Brace came up with another idea. He decided to try and move these children across the country, far away from the crowded cities, to the rural parts of the Midwest, where families could adopt them and offer them a better life.

Brace’s theory was that if the orphans and homeless children were removed from the awful conditions they lived in and settled into a healthier environment where they would be raised by a kind and hard-working family, they’d be happier and, ultimately, their lives would be much better. Brace also knew that there was a huge need for labor in the developing regions of the Midwest. He believed that this would be a good opportunity for children in need to be adopted by farmers and land-owners. Brace thought that the children would be welcomed and considered as part of the families. Soon, everything was set in motion.

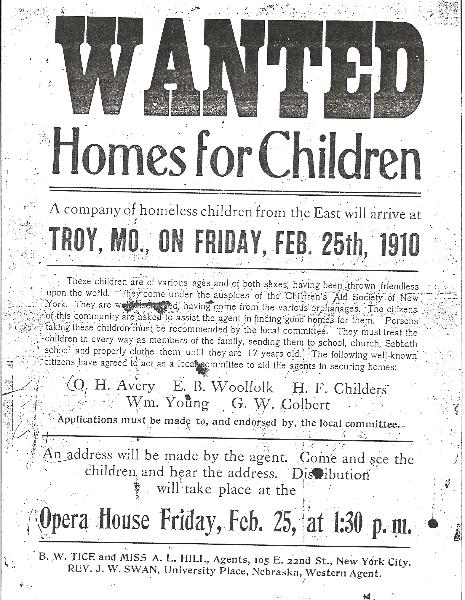

On October 1, 1854, after a very long trip in terrible conditions, a group of 45 children led by E. P. Smith (a representative of the Children’s Aid Society) arrived in Dowagiac, Michigan. The first try had many flaws. First of all, Smith gave two of the children to random passengers that he met on the journey, without even checking their background. Later, he took with him another boy that he met at a railroad station. The boy claimed to be an orphan, but Smith never checked if this were true or not. In Dowagiac, Smith gathered the local folks and presented the children as if they were some kind of product. He told the people that the children were handy to complete all sorts of tasks around the farm and in the house. Nevertheless, after a week, Smith managed to give away almost all of the children for adoption. Eight of the children that weren’t fostered were sent to Iowa City, where Reverend C. C. Townsend received them in his orphanage and tried to find suitable families for them.

According to the Children’s Aid Society, their first mission was a success. After a few months, encouraged by their initial success, they organized the adoption of two more groups of children, this time in Pennsylvania. After one year, the Children’s Aid Society sent small groups of children to many farms in Connecticut, Pennsylvania, and rural New York. Now they were ready to do things on a bigger scale. In September 1854, they started sending children farther across the Midwest.

Of course, this kind of undertaking demanded a lot of money. In order to get the funds, Brace wrote many articles in various newspapers and gave speeches in which he explained the importance of his work. Most of the money came from rich benefactors.

Some of them, like Augusta Gibbs (the wife of John Jacob Astor III), financed entire train loads of children. By 1884, Augusta Gibbs paid for the trips of 1,113 orphans. The railroads also helped by giving discounts for the journeys of the children and their caretakers.

It is important to note that although the term “orphan train” was first used in 1854, it was not heard by most people until 1978 after CBS broadcast a TV show called “The Orphan Trains.” During the time of the orphan train program, people used terms such as “family placement” or “out-placement” (because children were taken “out” of orphanages and taken “in” by families). The Children’s Aid Society department that was responsible for sending children to be adopted was first called the Emigration Department, or Home-Finding Department, and later it changed its name to Department of Foster Care. The term orphan train was avoided because less than half of the children were truly orphans. Many of the children that were sent had two living parents but were taken on the trains because they were mistreated, left on the street, or given away by their parents because of poverty. Some of the older boys and girls got on board just because of the free ticket.

The Children’s Aid Society had some rules for the families that decided to adopt a child. According to these rules, the family was obliged to raise the children as their own. They needed to give proper food and clothing to the children, and pay for their basic education. After the child turned 21, the family was supposed to give them $100. Those who were already older than 21 needed to be paid for their work. Although the children were considered as adopted, no legal document specified that.

The orphan train program was organized with the best of intentions for the children, but not all went perfectly. In fact, the system had many flaws, and some children were abused or treated like slaves, or like objects on sale at an auction house.

Places for babies were easiest to find. Most people preferred to adopt a baby. But placement for those older than 14 was difficult. People believed that it was too late for those children to change and that they could have a lot of bad habits and bad tempers. Children who were physically or mentally challenged were not quickly adopted. Another issue appeared with siblings. Although they were sent on the trains together, families were given the right to choose only one child and separate them.

In some cases, some families placed orders for specific children, demanding a certain age, gender, eye color, etc. Probably the worst element of the whole program were the exhibitions of children in local playhouses.

When the orphans arrived in a certain place, they were taken to the playhouse, where they were put on stage and took turns telling their names and singing a song. During this horrible performance act, people often came close to the stage, looked over, and touched the children, and even opened their mouths to check their teeth. It is believed that the term “up for adoption” came from this specific moment in history.

In schools, the children from this program were often the target of prejudice. They were bullied and called ”train children.” In some families, they were always looked upon as outsiders. People in some areas had trouble accepting them, thinking they were merely the offspring of socially undesirable people.

It is interesting to mention that at the beginning of the program (from 1855 to 1875), children were sent to U.S. states in the North and Midwest, but not any of the Southern ones, because Brace was an abolitionist.

As years passed by, the foster-home program of the Children’s Aid Society started to lose it strength. States from the Midwest got more settled, and people no longer needed the help of the orphans from the East. Besides, these states needed to deal with their own emerging orphans and homeless-children problem. In 1895 Michigan made a new law which prohibited the adoption of children that are not from the state. Many other states followed this example. The orphan-train program continued to exist on a smaller scale because of a few agreements between New York charities and a couple of states in the West. This lasted until 1929, when charity organizations changed their system. Instead of sending children across the country, they started taking care of all the families in need. This way, the number of homeless children began to get smaller.

In the period between 1854 and 1929, in which the program was active, a total number of around 200,000 orphans and homeless children were resettled and adopted. According to the Children’s Aid Society, about 85 percent of those children became “decent members of society,” while the rest either returned to New York or got arrested.

We will never know the exact rate of success of this program, but one thing is sure–Brace and his organization paved the way for modern-day foster care. His pioneering work in child adoption served as a good lesson for the future generations, who learned from the mistakes of orphan train program. Today, foster care is taken very seriously, and the happiness and well-being of the children is always the highest priority.