On April 22, 2017, a nonprofit club founded a century and a half ago held its annual meeting, which, as usual, took place at the Victory Service Club in Central London. The members, open-minded social elites, came from all over the world to sit under dim lights at the round table placed in the middle of the largest office and talk for hours and hours on pressing matters and delve into heated debates over a concern that, after a whole long year of waiting, just had to be addressed that very evening. The existence of ghosts.

It may sound silly today to even raise the question, but in the 19th century it was a matter of great concern indeed. Spiritualism was just as important as the feminist movement and that of the abolitionists. In Victorian times, talking about women’s rights, after Elizabeth Barrett Browning first raised the “big question” on what ought to be woman’s “proper” place in society, or talking of freedom and life in general, was surprisingly on the same level of interest for people as the afterlife and the existence of some strange ghostly apparitions. And of how, when, or why they exist, if they do.

With everything going on after the Industrial Revolution in the 1840s, which “allowed us, for the first time, to start replacing human labor with machines,” as Vitalik Buterin, the co-founder of Bitcoin Magazine, once declared, it was a time when the rich got richer in an instant, and the poor, well, they completely crashed just as fast, it is no surprise.

Those replaced by the more affordable machinery, now without a job or a buck to buy food, or medicine to survive the yellow fever epidemic, were dying, untimely, prematurely. If not them, then their loved ones. And when the fever were not enough, then came was the uncontrollable widespread cholera to finish them off. One of the most dreaded diseases known to humanity, at the time it swept the streets of England and killed every jobless, homeless, and “worthless” man or woman deemed surplus to requirements.

Ergo, everyone left behind, grief-stricken, was more than willing to pull their last dime out of their rotting shoe and pay for a chance to see those now sorely missed and say their last goodbyes.

In these grievous times, men who clearly understood what Thomas Carlyle was talking about when he said “teach a parrot the terms supply and demand, and you’ve got an economist” saw an opportunity to be more than a parrot and transformed into self-proclaimed psychics. They were mediums for the dead in a high-demand market created by the broken-hearted who preyed on these people’s naive hope by providing all kinds of ways to meet their need of reconnecting in exchange for that last dime these poor folk had in possession.

Lies, tricks, and hoaxes were virtually everywhere on every corner, and men published books to back their claims about the presence of the supernatural and their own spectral adventures. Secret societies were formed to pursue this newborn interest in the paranormal, and just like that, to chit-chat with ghosts came to be a new cultural thing in England, for the elite and hoi polloi. For believers and skeptics alike.

It was the trend then, and while many spoke of their “powers” and their otherworldly rendezvous, earning money out of it along the way, a couple of prominent thinkers and leading intellectuals rose above it all to organize investigations into these alleged encounters with the supernatural. They founded a club solely committed to exposing those men as frauds if needed.

It was the 1860s, and these luminaries represented a league of not so ordinary gentlemen “who used their combined book smarts in attempt to prove or de-bunk claims of the otherworldly” (Kelly McClure, Destination America). Their elite club, the first official such body to focus on the paranormal, was simply called the “Ghost Club” and its members, acting as mythbusters per se, it is said were led by none other than Charles Dickens.

A few years back the author had penned A Tale of Two Cities, which analyzes some of the important socio-economic aspects of the Industrial Revolution in Paris and London, so he probably knew a thing or two about the state of people at the time, and most importantly understood the logic behind this newly formed belief in the afterlife. He was not a non-believer by any means. On the contrary, he kept an open mind and was more than willing to explore the field, having written fiction on the matter himself (A Christmas Carol and The Signal-Man). Moreover, he was interested enough to pursue his curiosities and did try once to magically cure a friend. It was an experience explained in detail in some of his letters, telling exactly how he got rid of the horrible “feelings” that plagued Augusta de la Rue’s miserable existence.

Yet, as a man of great intellect and vast general knowledge, Dickens was above all else a man who could distinguish between someone who was experimenting in uncharted territories in search of the truth and a fabricator in search of loot. And he was after the latter, as were all the others members of the Ghost Club. First on their list were the Davenport brothers.

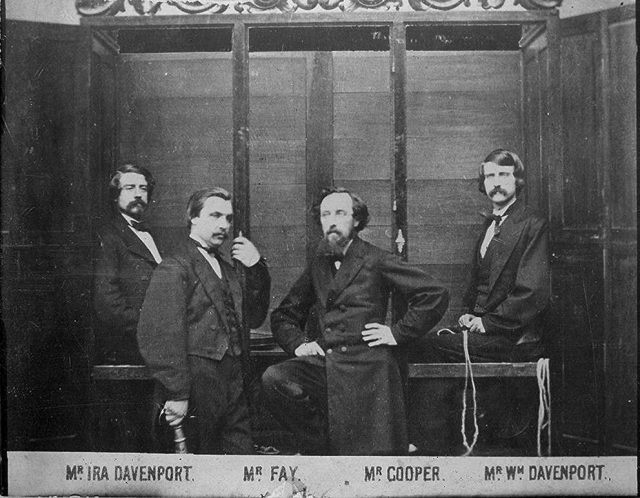

Two American boys, who upon hearing that spiritual madness had overtaken reason and sanity in England, had decided to cross the pond and bring their famous act, along with their alleged “spirit cabinet,” from New York City to London. It was said that the boys were special, and the box was a portal for the restless. Many witnessed the boys being placed inside the box, tied up and unable to move. They were startled to hear a piano play Bach inside, by itself, after the box was closed, and they were obscured from sight. Someone from the other side was surely trying to say something, and this was the only way, for the box was found lost and forgotten at a place where no soul dared to look, and the boys were still tied up as they were before the box was closed in front of the audience.

To their surprise and misfortune, as it turned out, our investigators were actually fond of Bach and were there to hear how a piano would play his compositions without a pianist and, to an extent, to determine if their act was legit spiritual and if the brothers, Ira and William, were really in the company of a dead pianist inside, which they weren’t of course. They were just ordinary magicians with a trick up their sleeve who advertised it as something more than it was. At the end, they were exposed for who they are, and not just by our Ghost Club, but by many others after them. Including George Alfred Cooke, who re-created the same cabinet and explained how their illusion was achieved in detail.

After that and in the upcoming years, the club managed to successfully de-bunk more than 2,000 cases similar to the Davenport Brothers, according to the North British Review. Men such as Siegfried Sassoon and William Butler Yeats joined the ranks of the all-men secretive club. It was secretive in terms of content and what was spoken inside the club’s chambers, although outside almost everyone knew of its existence by now, renowned for its critical approach in a country that was willing to accept every little magic trick as something much more. They even openly mocked “the commercial tone which has been given to the subject,“ as Dickens wrote in An Unpatented Ghost in 1865, explaining how spiritualism was used most times to deceive the gullible in search for profit, and “that nothing must be taken for granted, and every detail proved by direct and clear evidence, before it can be received,” as he wrote two years before.

However, around 1870 new members joined the ranks, among whom was Sir William Crookes, who, unfortunately, as it was revealed later on, lacked that critical approach that made the club popular, and most of their activities slowly but surely shifted from critical to promotional. The club began to attract bad press and Dickens, staying true to his beliefs, left the club. He died on June 9 of that year, leaving us with something he wrote to his friend William Howitt before he passed away. Words that still echo powerfully, not just on the subject of spiritualism but in almost every single one:

“My own mind is perfectly unprejudiced and impressible on the subject. I do not in the least pretend that such things are not. But … I have not yet met with any Ghost Story that was proved to me, or that had not the noticeable peculiarity in it—that the alteration of some slight circumstance would bring it within the range of common natural probabilities.”

The club, now without a strong identity, started to crumble, and its members, without clear and unified views, left the club altogether. Some who wished to walk down the investigative road joined a new organization, the Society for Psychical Research, which was formed in 1882. It was a club that embraced the ideology of the Ghost Club when it was formed in 1862. It seems that those who only wished to promote themselves joined the ranks of a “new” Ghost Club, founded by William Stainton Moses, who strangely enough was also the founder of the first mentioned. Who knows, maybe humanity was in desperate need of both.

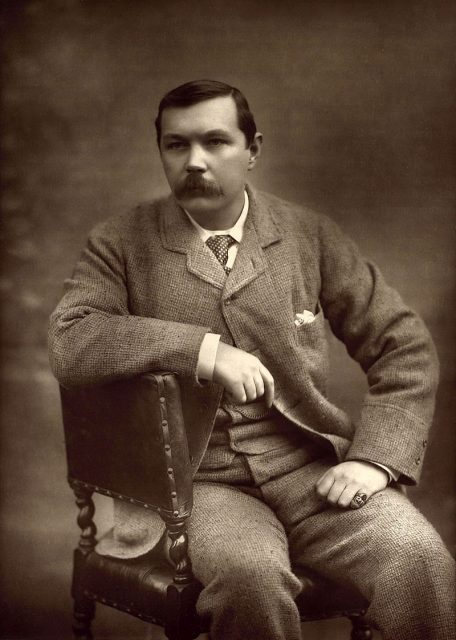

Among these, aside from the founder who made sure to tell everyone that “a club of similar name, founded some twenty years earlier, had come to an end, and has no connection with this 1882 Ghost Club” was Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, which is rather odd and confusing, bearing in mind that both clubs represented complete opposites.

Anyhow, by supporting and sponsoring all kinds of different mediums, including agents of the “spirit photography” movement, such as William Hope, Édouard Isidore Buguet, and Frederick Hudson, who were all exposed as frauds in no time, the organization that believed they were true spiritualists and had true connections to the after-world, as expected, didn’t last for long. As for Doyle, well, he fell victim to a hoax in 1920 and lived to see his reputation crumble under his feet.

Harry Price, the man who exposed William Hope and brought shame to one of the most reputable investigative writers in history, revived the club once again in 1936 and became its chairman.

That new Ghost Club, one that embraces spiritualism and promotes it, but cautiously and critically as Dickens first intended, lives on. They openly invite any “genuinely open-minded, curious individual, whether an interested skeptic, an academic, or scientist” to join in and debate what’s real. And according to Andreas Charalambous, their current public relations agent, a lot of “lecturers, barristers, librarians, doctors, members of the police force, and a whole lot of public figures” actually do, at the round table at the Victory Service Club in Central London.