Of all the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, it is only the Great Pyramid of Giza that has survived the passing of time. Also known as the Pyramid of Khufu or the Pyramid of Cheops, in the ancient world, it was the oldest of all the seven wonders.

According to Egyptologists, it likely took up to two decades for the Great Pyramid to be completed. While its construction was concluded somewhere around 2560 BC, the pyramid stood as the tallest man-made structure in the world for more than 3,800 years.

Without doubt, it’s the best-known relic of the world of the ancient Egyptians and the many striking facts of how it was built, its historical use, and what it holds have always made for intriguing stories to hear and learn from.

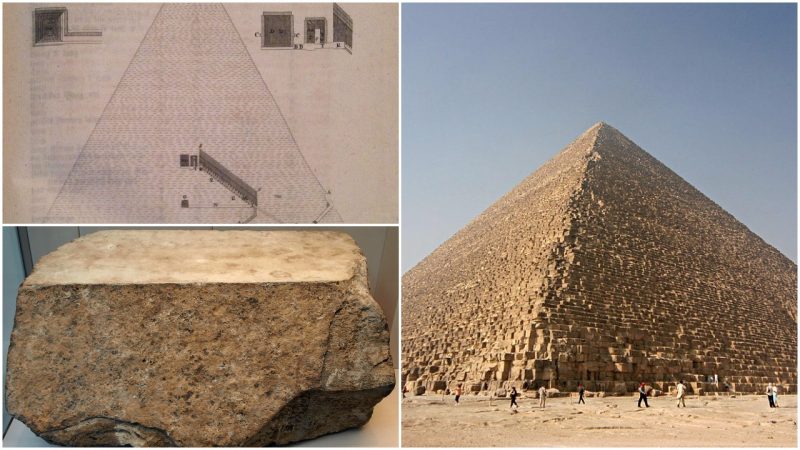

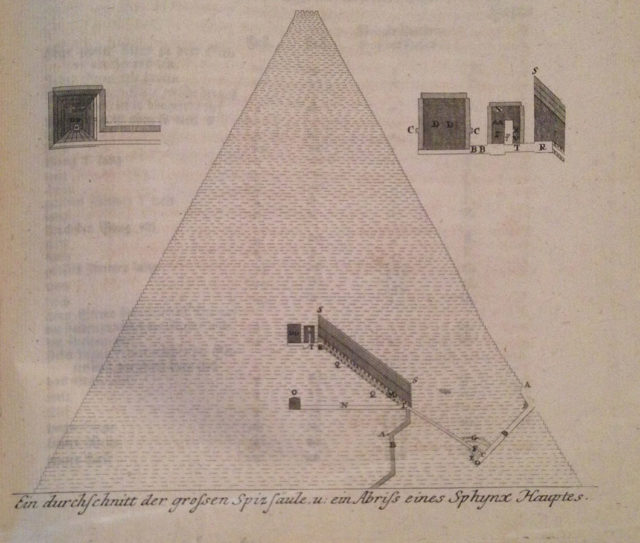

Estimates suggest that the Great Pyramid consists of roughly some 2.3 million blocks. The Tura limestone blocks used for its casing were taken from nearby quarries, just across the river. However, some of the largest granite stones, like those found in the so-called King’s chamber, were carried all the way from Aswan, which is more than 500 miles away. The heaviest granite stones weight up to 80 tons.

As tradition has it, the ancient Egyptians would cut stone blocks by hammering wooden wedges into them. They would then soak the blocks in water, and as the water was absorbed, the wedges expanded. This caused the rock to crack. Once they were cut, the stones were carried by boats along the Nile, on their way to the construction site.

For the needs of the Great Pyramid, it is deemed that some 5.5 million tons of local limestone and as much as 8,000 tons of granite brought from Aswan would have been used. Added to this material was the 500,000 ton of mortar needed in the pyramid’s construction. What is perhaps even more impressive is that once it was completed, the Great Pyramid was surfaced by white “casing stones.” These casing stones were intricately cut, beautifully polished blocks of white limestone.

The ancient builders needed to cut these particular pieces of stone extremely carefully so as to fit correctly. When they were added to the pyramid, during the final stages of its construction, the casing stones gave it a smooth and flat finish, unlike the one we are accustomed to seeing today.

We might wonder what happened to the casing stones? The answer to this question takes us back in time, to 1303 AD, when the Great Pyramid survived a huge earthquake. While it did not collapse, many of the pyramid’s outer casing stones were loosened by the quake.

After that, an amount of casing stone was carted away by Bahri Sultan An-Nasir Nasir-ad Din al-Hasan, in 1356, to use as material for building mosques and fortress in nearby Cairo, the capital and the largest city of modern-day Egypt. In addition, plenty more casing stones were removed from the Great Pyramid by Muhammad Ali Pasha during the early 19th century and reused as material for his Alabaster Mosque, also in Cairo.

As Western explorers started arriving at the site of the Great Pyramid of Giza, their first reports tell of massive piles of rubble found at the base of the timeless edifice, leftovers of the perpetual collapse of the casing stones. These piles were thereafter cleared away as excavations on the site proceeded. Nevertheless, remnants of the limestone casings can still be found set around the base of the Great Pyramid and is enough to show the craftsmanship and precision that has repeatedly impressed across the ages.

The English Egyptologist Flinders Petrie would compare the precision of the casing stones to being “equal to opticians’ work of the present day, but on a scale of acres.” He further remarked that “to place such stones in exact contact would be careful work; but to do so with cement in the joints seems almost impossible.”

Many theories attempt to answer the question of how this architectural wonder was accomplished, and oftentimes the answers contradict one another. The Greeks believed that slave labor was used, but more contemporary theories assert that the building of the Great Pyramid took the workforce of probably tens of thousands of skilled workers organized in groups hierarchically.

Whichever it was, the ancient Egyptians indeed managed to construct a structure that did stand the test of time, a seemingly near impossible task but, as it turns out, still attainable.