There has been a stream of discoveries in the last 12 months that suggests a need to move back the dates of our early ancestors’ migration out of Africa. Modern human fossils uncovered in Asia, as well as new DNA studies, have pushed back the occupation of that continent from 60,000 to 120,000 years ago. Stone tools and hominin fossils discoveries suggest that archaic Homo sapiens inhabited parts of Eurasia well before 200,000 years ago, at least 300,000 to 400,000 years ago.

These suggested revisions to the human story may sound major, but they are extremely conservative considering the greater body of evidence available. There is a good reason to believe our early ancestors migrated out of Africa 2 million years ago; for some peculiar reason, the public almost never hears about this in the mass media. It may at first sound so extreme that it must be a fanciful revision, but it is incredibly reasonable and supported by a wealth of sound scientific evidence. “It was not until around 2 million years ago that human ancestors first migrated out of Africa and spread throughout the Old World,” said Rolf Quam, associate professor of anthropology, Binghamton University, State University of New York.

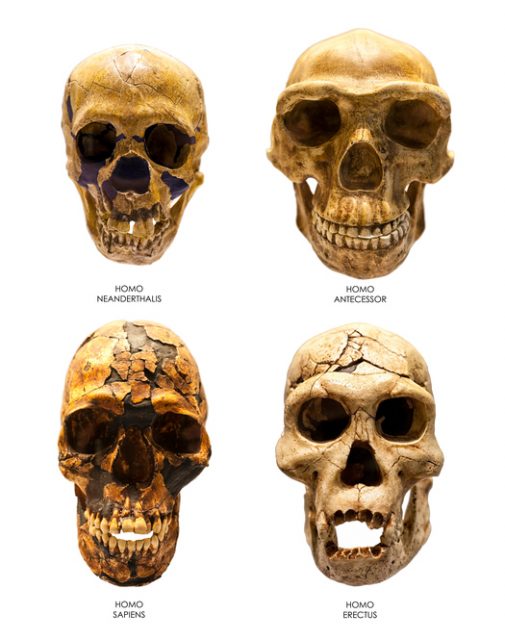

Today scientists almost unanimously believe that modern humans can trace their origins back to a population of hominins that appeared in the African fossil record around 2 million years ago, Homo ergaster. That Homo ergaster is our direct ancestor has never been established for certain, and there has always been a second strong contender, Homo erectus. We know that Homo erectus and Homo ergaster were once part of a single population; 2 million years ago they were simply two regionally separated populations within a single species.

Homo erectus did something that no other hominin before it had managed, it conquered the planet. Today fossils place members of this hominin species at sites as disparate as the Georgian Republic and Indonesia as early as 1.8 million years ago. Groups of Homo erectus made their way into almost all habitable regions in the hundreds of millennia which followed this initial expansion, a few skull fragments in America have even been claimed as evidence they were the first to reach that continent (though such claims remain highly contested).

Changes in environment or climate are understood to be the primary drivers of evolutionary adaptation, just as need is the mother of innovation. Homo erectus would have faced incredible challenges as it moved into alien environments beyond the African continent. These intrepid explorers would have encountered unknown animals, many of them dangerous predators, and explored unfamiliar landscapes such as icy tundra, deserts, tropical rainforests, and coastlines while passing through a wide range of climates. Their survival would have been dependent on flexible thinking, innovation, and rapid adaptation. When you apply basic logic, it seems obvious that Homo erectus had entered the evolutionary fast lane by exiting the familiar and relatively static environment within the African motherland.

Meanwhile, back in Africa, Homo ergaster would have been under little pressure to change, being highly adapted to the African landscapes and climate, the forces responsible for human evolution would have been running in a low gear, restricted to at most negligible levels. Evolutionary changes would still inevitably occur for these hominins, but there is little reason to think it would have occurred rapidly or produced any profound modifications. There are numerous examples of well-adapted organisms in almost static environments that have barely changed over millions of years.

You are almost certainly wondering why academics favor the stay-at-home stick-in-the-mud Homo ergaster as a prime candidate for our Homo sapiens ancestor, rather than the dynamic and entrepreneurial Homo erectus.

The decision to favor Homo erectus’s African cousin was based largely on assumptions, as hominins appeared first in Africa and evolved into new forms there over millions of years, and the earliest definitively Homo sapiens fossils were found within that continent’s boundaries, and so it was assumed they evolved there from earlier hominins. There was, of course, a huge time gap between Homo ergaster and the emergence of Homo sapiens. There was also an enormous change in the morphology (physical form) during that separating period. The scientists needed fossils representing a series of transitional human forms that would connect these two populations.

With the discovery of Homo heidelbergensis, it seemed that the missing link, or one of them, had finally been uncovered. Sometime around 600,000 years ago, this large brained hominin named Homo heidelbergensis appeared in the fossil record across Africa, Europe, and Asia. With a strong contender for a direct, immediate ancestor of Homo sapiens identified in Africa, the case for an Out of Africa Homo sapiens model seemed almost certain. It seemed only a matter of time before an earlier hominin would be found that linked Homo heidelbergensis to Homo ergaster. That was of course until the best contender for Homo sapiens ancestor was knocked out.

Research revolving around a large collection of hominin fossils in Northern Spain (Sima de los huesos) has revealed that Homo heidelbergensis emerged after the split between the ancestors of modern humans and those of Neanderthals, with Homo heidelbergensis being exclusively an early form of Neanderthal. There are now no fossils representing a viable ancestor for modern humans anywhere in Africa earlier than 300,000 years ago. We also lack evidence of the evolutionary transition between Homo ergaster and Neanderthals, or Denisovans, in the African record.

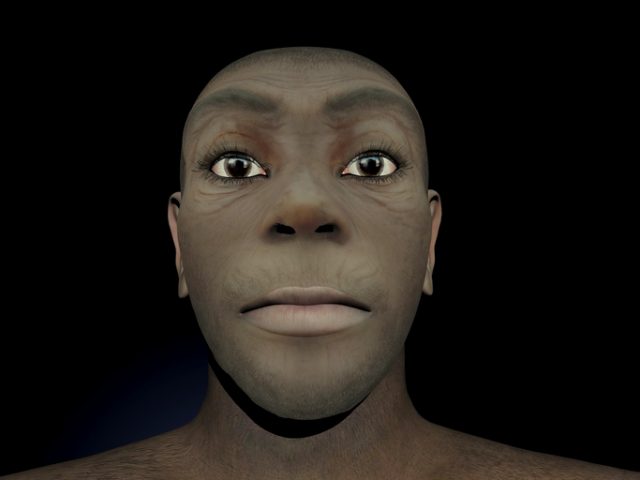

When you put all this information together and apply logical deduction, the existing evidence points towards all three large-brained hominin lineages emerging from Homo erectus somewhere far from Africa, perhaps East Asia. Sporadic migrations of transitional human forms gradually brought these populations into Africa in waves as climate changes drove them towards preferential locations. While Africa suddenly has a glaring lack of suitable transitional fossils, East Asian scientists are announcing a growing list of potential candidate finds.

“The tale is further muddled by Chinese fossils analysed over the past four decades, which cast doubt over the linear progression from African H. erectus to modern humans. They show that, between roughly 900,000 and 125,000 years ago, east Asia was teeming with hominins endowed with features that would place them somewhere between H. erectus and H. Sapiens,” said Wu Xinzhi, palaeontologist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology.

With the recent announcement that the 260,000-year-old Dali Skull in China is that of an archaic Homo sapiens, and Levallois type stone tools (usually associated with these archaic Homo sapiens) in India date to 385,000 years ago, the case for an Asiatic genesis of our species has strengthened incredibly. The only thing missing here is direct evidence that early Homo sapiens migrated into Africa, surely that would be the final proof?

In September 2017, a team of scientists from Buffalo University announced that they had made an astonishing discovery while investigating a saliva protein in humans, designated as MUC7. The team realized that a significant number of Sub-Saharan Africans carried a wildly different variant of the MUC7 gene to members of all other sampled populations, suggesting to them that the ancestors of these people had interbred with another ancient human species. The date for this interbreeding appeared to be around 200,000 to 150,000 years ago, and the hominin species responsible was calculated to have diverged from our direct ancestors between 1.5 to 2 million years ago.

The dates suggested in the MUC7 study are nothing short of incredible. On the one hand, we have a date close to the first clear expansion of early modern humans across Africa, and on the other hand, we have a date range that meshes well with the divergence of Homo erectus from Homo ergaster.

“This unknown human relative could be a species that has been discovered, such as a subspecies of Homo erectus, or an undiscovered hominin. We call it a ‘ghost’ species because we don’t have the fossils,” said Omer Gokcumen, assistant professor of biological sciences, Buffalo University.

The scientists also realized that non-African modern humans carried a variant of MUC7 that was much the same as that carried by Neanderthals and Denisovans, both of which are accepted as Eurasian archaic hominins. Somehow the scientists failed to make the final leap towards the most obvious conclusion.

If Homo sapiens evolved in Eurasia, alongside Neanderthals and Denisovans, from an Asian Homo erectus last common ancestor resident there, it would be no surprise they all carried a similar MUC7 gene. As some groups of early modern humans migrated into Africa around 200,000 years ago, they would have inevitably encountered any descendants of Homo ergaster, perhaps hominins like the species Homo naledi, known to have inhabited South Africa until at least 236,000 years ago. The fact that the modified version of MUC7 is common across Africa also suggests it entered the human genome almost as soon as the first population of Homo sapiens appeared in Africa before they split into separate regional groups.

Conversely, if Homo sapiens evolved entirely within Africa, how did they avoid interbreeding with a nearby, sexually compatible, neighboring human species for well over a million years?

Related story from us: Oldest non-African modern human fossil revealed to be 195,000 years old

Why is it that, if non-African modern humans migrated out from Africa long after 150,000 years ago, the variation of MUC7 common across that continent is found in none of the supposed descendants of these migrants living across Eurasia, Australasia and America?

The media and the scientists are right, we need to revise the dates for when our early ancestors left Africa, but not by a few tens of thousands of years. We need to accept the obvious truth, our direct ancestors were already out of Africa at least 1.8 million years ago.

Bruce R. Fenton is a researcher of human evolution and ancient hominin migrations, with a special focus on the rise of the first /Homo sapiens/. Fenton is the author of the pop-science book ‘The Forgotten Exodus: The Into Africa Theory of Human Evolution,” as well as a regular guest writer for several online magazines. His research interests have taken him to all six inhabited continents and led to his being featured in the UK Telegraph and acting as an expedition leader for the Science Chanel. He is a current member of both the Palaeoanthropology Society and the Scientific and Medical Network.