This was probably the most infamous mutiny that happened off the coast of Australia, and perhaps the largest that happened anywhere else in the world. On 27 October 1628, a ship called Batavia, belonging to the Dutch East India Company, set sail on its maiden voyage from the port of Texel in the Netherlands.

The ship, commanded by senior merchant Francisco Pelsaert, was carrying huge amounts of silver and gold. It was bound for the Dutch East Indies where it was supposed to trade the treasure for spices.

Since the beginning of the journey, something wasn’t right. Among the 341 people on board (crew and passengers) there were some really shady characters. Some of them would become the main antagonists in this dreadful story. Second in command was Ariaen Jacobsz, the skipper. It is speculated that he and Pelsaert previously met in Surat, India and were not on the best terms.

Another suspicious man on that boarded the ship was junior merchant Jeronimus Cornelisz. He was a bankrupt pharmacist from Haarlem, fleeing the Netherlands. Cornelisz was accused of his heretical beliefs. He feared prosecution because of his connections with Johannes van der Beeck (Torrentius), a Dutch painter and alleged Rosicrucian follower and a supposed believer in satanic ideas.

Soon after the voyage began, Jacobsz and Cornelisz got to know each other and developed a plan to take over the ship. Their idea was to take the gold and silver and start a new life in a distant land. Batavia made a short supply stop at Cape Town, and after they had set sail again, Jacobsz managed to steer her off the main course and separate her from the fleet. Up until then, Jacobsz and Cornelisz were working on convincing a small group of people to join them. With the ship safely distanced from the rest of the fleet, they began to arrange an incident that was to trigger a mutiny.

Their plan was to harass a wealthy female passenger in order to motivate Pelsaert to “unjustly” discipline the crew, hoping that this would inspire more people to join their side. The target was a girl called Lucretia Jans. This attempt failed because she was able to identify the attackers. Jacobsz and Cornelisz decided to wait for Pelsaert to arrest the sailors and then make their move, but that never happened.

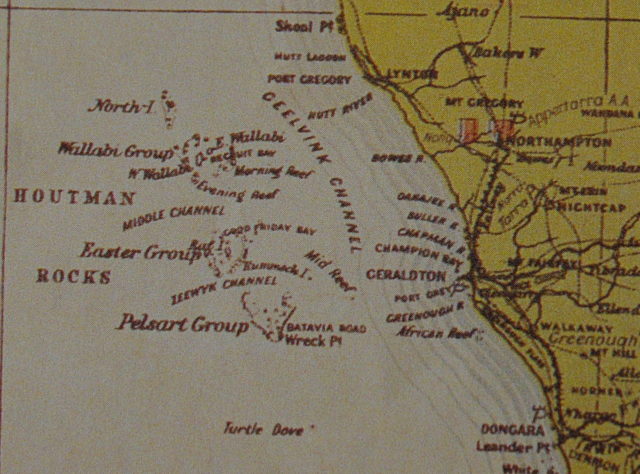

On 4 June 1629, the Batavia struck a morning reef near Beacon Island in the Abrolhos Islands chain. Most of the people managed to swim to safety on Beacon Island, but 40 people weren’t so lucky and drowned. This was nothing in comparison to what awaited the survivors in the following months. The events that follow are one of the most gruesome in early Australian history.

After searching for food and water, the survivors realized that their situation was bad. No fresh water source was found, and almost no food was in their vicinity, besides sea lions and birds. A group lead by Francisco Pelsaert and comprised of Skipper Jacobsz, some senior officers, crew members, and passengers, decided to sail to the mainland in a 30-foot longboat.

This trip was also unsuccessful; no water was found there either. With no rescue on the way, Pelsaert decided to go and bring a rescue ship from the city of Batavia (modern-day Jakarta) on Java. He took the same group of people on the longboat and started an epic 33-day journey. He successfully reached Batavia, and no one died during the journey. This is considered as one of the most difficult journeys in an open boat even today.

When they arrived in Jakarta, Jacobsz was arrested for negligence while the Governor General, Jan Coen, gave Pelsaert command of a ship called Sardam to go and rescue the other survivors. He returned to the shipwreck two months later after he set sail from Jakarta.

In the meantime, Jeronimus Cornelisz appointed himself in charge of the rest of the survivors. Fearing that Pelsaert would return and accuse him of mutiny, he prepared to hijack the rescue ship and escape. In order to do this, he first needed to get rid of all those who posed a threat to him. He first organized all the food and weapons under his control and sent a group of soldiers, led by a soldier named Wiebbe Hayes, to the nearby West Wallabi Island. He promised to send people to save them if they find water and food there. In fact, he left them there to die.

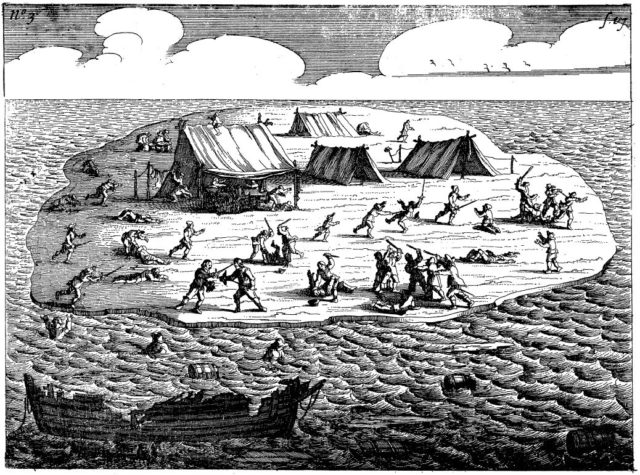

With all the threats removed, Cornelisz started his dictatorship over the rest of the survivors. He began killing anybody that he considered a threat. According to some accounts, he only killed one person himself; all of the other killings were made by a group of vicious men under his command.

To make things even more terrible, he kept the women in so-called “rape tents.” His plan was to reduce the population on the island down to 45, in order to prolong his supply reserves as long as possible. Cornelisz and his gang of murderers killed over 110 men, women, and children. In the beginning, he persuaded those evil men that the victims had committed crimes such as theft, but later, the mutineers began to kill just for pleasure and because they were bored.

Meanwhile, the soldiers on West Wallabi Island managed to find sources of water and food to survive. Unaware of the massacre happening under Cornelisz’s rule on the other island, they sent smoke signals announcing their finds. After some survivors escaped from Cornelisz and informed them about the monstrosities, the soldiers started to prepare for defense from the mutineers. They even built a small limestone and coral fortress. When the insurgents attacked, they were no match for the better trained and protected soldiers and lost the battle.

At this moment, the rescue ship was close, and a race for the ship started between Cornelisz and his group and the soldiers led by Wiebbe Hayes. Hayes managed to reach the Sardam first and explain the situation to Pelsaert. A short battle happened after this, and Pelsaert together with Hayes managed to capture all of the mutineers.

Pelsaert was gone for three months, and during that time Cornelisz and the mutineers killed 125 men, women, and children. In his book, Batavia’s Graveyard, the Welsh author Mike Dash claims that Cornelisz was almost probably a psychopath. In his research, he found out that on many occasions on the island, Cornelisz displayed erratic behavior: he had dreams of making a personal kingdom, and he was assured that all of his decisions and actions were justified because God himself inspired them.

Cornelisz and few of the worst mutineers were immediately punished; both of their hands were cut off, and they were hanged. Two of the mutineers that were not as guilty as the others were banished on the mainland. The rest of mutineers were brought to Jakarta for trial.

Five of them were hanged, and the rest were punished by flogging. Jacob Pietersz, who served as second in command on the island under Cornelisz, was punished on the breaking wheel, the harshest punishment at that time. Skipper Jacobsz was tortured, but he never admitted his involvement in the mutiny; he probably died in prison in Jakarta.

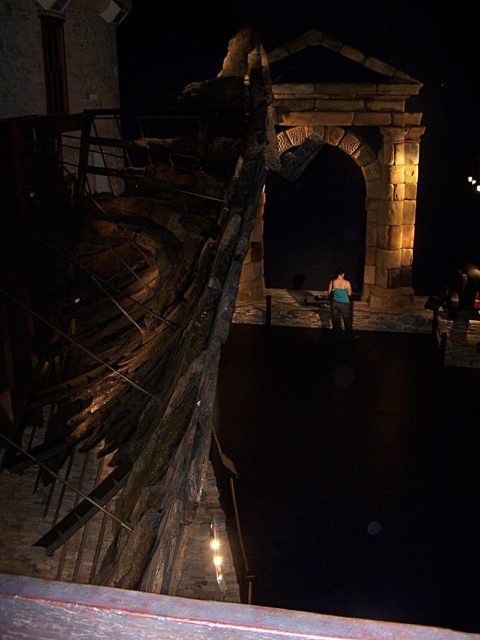

The wreck of the Batavia was discovered in 1963. Since then, many archeological discoveries have been made in the vicinity. Even 300 years later, discoveries about the destiny of its survivors are still found there. There is also a replica of the ship built in Lelystad, Netherlands. The replica was shipped to Australia in 1999. In 2000, Batavia was the flagship for the Dutch Olympic Team during the 2000 Olympic Games. Since 2001, the replica has been kept at Bataviawerf in Lelystad and is now open for visitors.