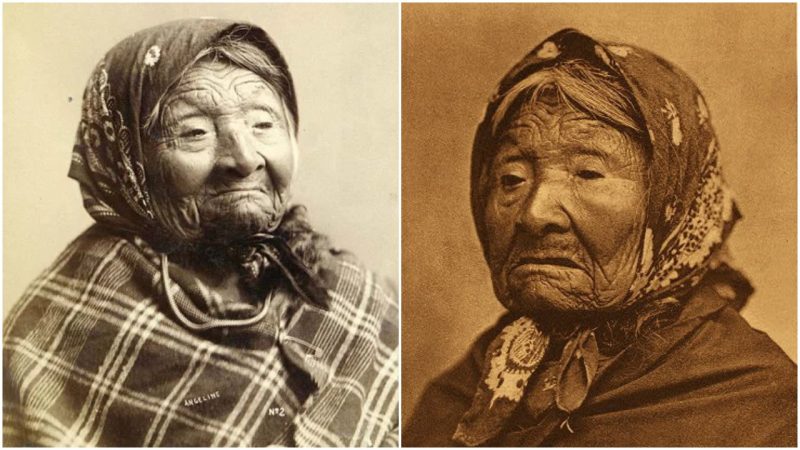

In 1895, the American photographer Edward S. Curtis took his first portrait, depicting a wrinkled woman with a red handkerchief over her head. The woman was Native American, and he paid her a dollar for her trouble. Later on, one of the portraits of her would make Curtis a widely recognized, internationally acclaimed photographer, as he went on to document through photography the lives of Native American tribes.

As much as Curtis’ story is compelling, it is the life of his first subject, the elderly woman with a weathered brow and down-turned lips, that stays with us. Known as Princess Angeline, she was Chief Seattle’s eldest daughter, after whom the city of Seattle took its name. She often posed for photographers to earn a little money, since she was a famous figure, a world-bridger who connected the indigenous peoples and the settlers.

Of course, Princess Angeline’s birth name was different. She was called Kikisoblu and was born in 1820 in the south of what is today the city of Seattle. Her father, Chief Seattle (Si’ahl), was an ancestral leader of the Suquamish Tribe and a Duwamish chief. When American settlers started arriving in the area, Chief Seattle befriended one of them, David Swinson “Doc” Maynard. It was Maynard’s spouse who was very keen on Kikisoblu and reportedly she went on to christen her in Christian faith. Hence her name Angeline.

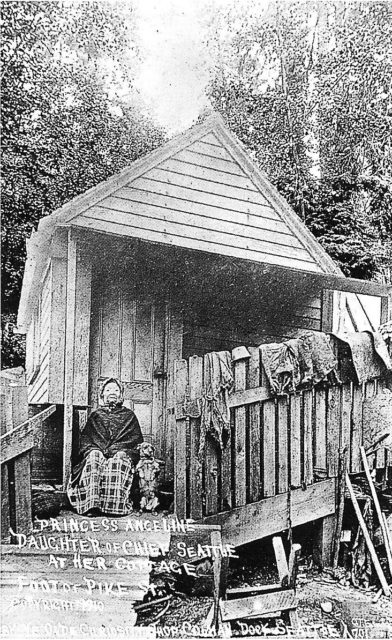

She gained the title “princess” because of her father, but also for her dignified stance regardless of her situation, one that escalated in the mid-1850s. At that point, when Angeline would have been in her mid-thirties, the U.S. government proceeded to carry out a treaty that forced the indigenous people in the area to move away from their land and relocate to a reservation. Instead of joining the exodus, Angeline refused to leave her Western Avenue home, a modest waterfront cabin in between Pike Street and Pine Street.

She built a new cabin on the same lot in the 1890s, a few years before her death. But when she died, even this last remnant of Princess Angeline’s life was sadly removed. After her death, the area became a part of the waterfront until Pike Place Market was formed.

In the latter part of her life, Angeline made a living by washing clothes, and she also sold native handicrafts such as baskets that she made in the evening. In those early years of Seattle, Princess Angeline was a famous figure in town. Photographers including Frank la Roche and Darius Kinsey visited to ask for a portrait of her, to which she agreed for a fee.

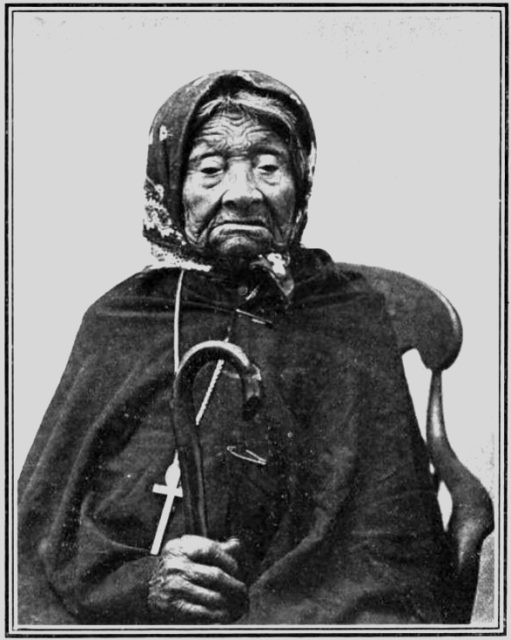

The courageous Native American woman was living in two worlds. One of those worlds was slowly fading away, and she was merely a ghost of it. The other one was the new modern world, where she was left alone and poor to face the problems that piled up as the years went by. At some point she developed arthritis, but she stood strong and never ceased her daily routines. She continued to be that recognizable figure on the streets of Seattle, wearing her shawl and her red handkerchief.

The locals were very keen on her, and some of them offered her some help, which she didn’t refuse. For example, she was able to take some free groceries from a local market very close to her cabin.

Princess Angeline practiced Christianity and was with the Roman Catholic Church until she passed away on May 31, 1896. Upon her death, she was given a funeral and was buried at Seattle’s Lake View Cemetery.

People came to write and say kind words for her service, and truly honor Chief Seattle’s last direct heir. Her coffin was in the shape of a canoe.