In the 1940s, the United States focused much of its industry on the war effort. The country’s production capacity turned out to be key for victory, as large amounts of raw materials and weaponry were sent overseas to help Britain and the Soviet Union stop Hitler and the Nazi war machine.

Due to the fact that much of civilian life was revolving around war production, people might not have spending their time thinking about toys.

That is, until Richard T. James, a Naval engineer from Philadelphia, discovered something purely by accident that would turn the toy industry upside down. He was working on a means for suspending delicate shipboard instruments that were part of internal equipment aboard naval vessels. The tension springs had to be extremely elastic, for they were intended to keep various instruments in check, even in rough seas and bad weather.

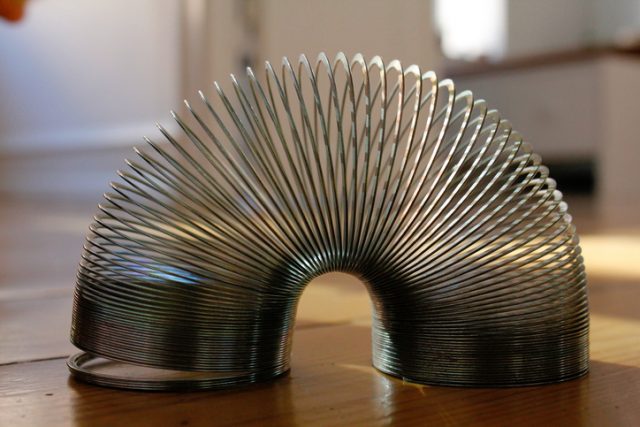

While working on these elastic springs, he accidentally dropped one. Due to the nature of the material and the form of the spring, it kept moving after it hit the ground. It was like a walk. At that moment, Richard James came up with an idea that would change his life forever. The way that the spring “walked” would become recognizable all over the world in the next few years.

James bought a coil winding machine and opened up a small business, called James Spring & Wire Company, which would be the base for the mass production of … the Slinky. It was James’ wife, Betty, who came up with the name while browsing through a dictionary. Also, it was his wife who made the first investment in her husband’s company, giving him $500 to cover initial expenses.

But before he marketed his product, this naval engineer did a thorough job of experimenting with various lengths and metallurgical formulas. He spent two years working on the perfect prototype.

The result was a spring that perfectly transfers energy along its length in a longitudinal wave. In a periodical motion, Slinky would descend end over end, resembling a step-by-step motion.

Around Christmas 1945, the couple pitched the idea to Gimbels Department Store in Philadelphia, who agreed to display Slinky in an aisle. The first 400 models, priced at $1, sold out in less than an hour and a half. After that, mass production was inbound.

Since then, more than 300 million units were sold. Even today, it is estimated that more than a quarter of a billion Slinkys are being sold per year all around the globe.

Even though the company became a huge success, Richard James was more obsessed with religious organizations, finally deciding to leave the business and join the Wycliffe Bible Translators in the 1960s. This religious organization was then based in Bolivia, where they practiced their dedication to translating the Bible into all languages of the world.

Betty James took the position of CEO in the James Spring & Wire Company and moved the base of operations from Philadelphia to her hometown of Hollidaysburg, Pennsylvania. Together with their six kids, she brought the original equipment used to produce Slinky’s and that equipment is in use to this day.

More than 500 different variants based on the Slinky design were produced later on, including the Slinky Dog and the Plastic Slinky. Apart from a memorable product, the company produced a really catchy jingle, which made them recognizable all over the United States:

What walks down stairs,

Alone or in pairs,

And makes a slinkity sound?

It’s Slinky…

Related story from us: Dresses from the sky: WW2 wedding gowns made from silk and nylon parachutes

Betty James lived to be 90 years old before she passed away, in 2008. The legacy she left, together with her husband, remains engraved in the Toy Industry Hall of Fame. A study made by the New York Times after her death concluded that the number of Slinkys sold since 1945 would be enough to circle the globe 150 times.