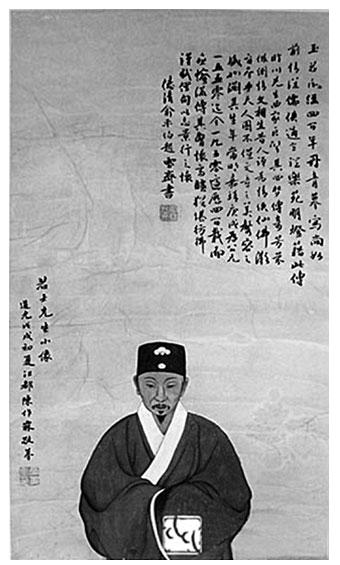

Tang Xianzu has been called the “Chinese Shakespeare,” but until recently, the resting place of the prolific Ming Dynasty poet and playwright remained a mystery. Then last summer, Chinese news agencies announced that archaeologists had uncovered what they report is Tang Xianzu’s grave. Though no bones remained, the Eastern Bard left an important clue—in writing, naturally.

Jiangxi archaeologists unearthed 42 Ming-era graves dating between 1368 and 1644 in Fuzhou, Tang’s birthplace, in the eastern region of Jiangxi, due south of Shanghai. Forty of them are assumed to belong to Tang’s extended family and retinue.

Six epitaphs thought to be written by Tang Xianzu were found in the family burial plot, which led archaeologists to believe he was entombed there along with his third wife, Fu. His second wife, Zhao, was entombed nearby. Though the site was uncovered in 2016, China’s news agency released news of the findings in 2017. @XHNews tweeted images of the excavated site in 2017.

“The epitaphs can help us learn more about the calligraphy, art, and literature in Tang’s time,” said Xu Changqing of the Jiangxi Provincial Cultural Relics and Archaeology Research Institute, according to Archaeology.

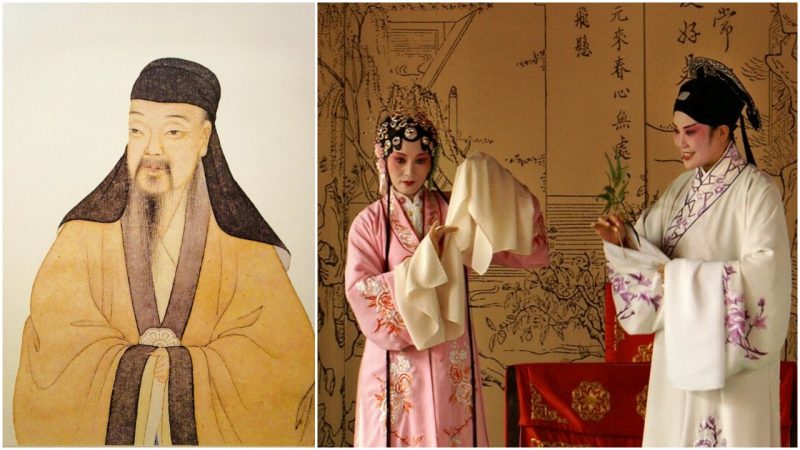

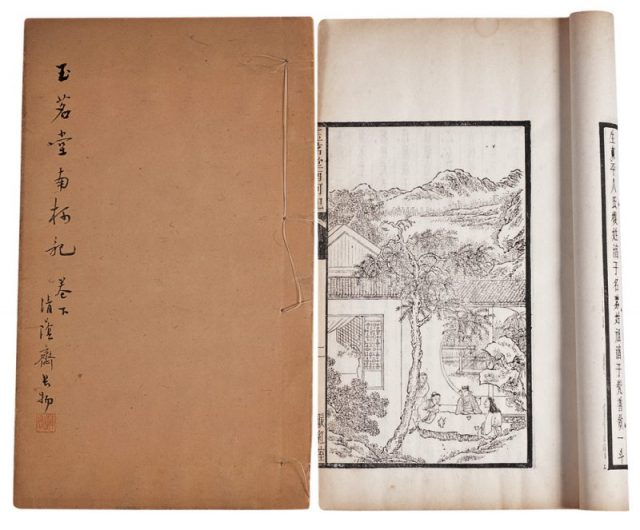

The major plays Tang wrote are known as the Four Dreams and include the romantic tragicomedy The Peony Pavilion, a work still performed on the Chinese Kun opera stage today. With its complex plot, dramatic structure, and fully realized characters, the Peony Pavilion is the most emblematic and enduring dramatic work of the Ming dynasty.

The Peony Pavilion is also an epic: When all 55 scenes are performed uncut, the play can run to a staggering 22 hours, according to NPR. It is more often performed in a much-condensed 75-minute version.

Tang was something of a renegade in his day. His plays celebrated the triumph of humanity over hierarchy, a daring concept in the Ming Dynasty, which revered rank, structure, and formality. In Peony Pavilion, a young noblewoman falls scandalously and fatally in love with an impoverished scholar. Heavens!

Such was the power and popularity of Tang’s plays that he became known as the “Chinese Shakespeare.” Indeed, both flourished during the same period. And both died on the same day, April 23, 1616.

Tang and Shakespeare never met, given the day and age and thousands of miles between China and England. They likely didn’t even know of each other’s existence. But that hasn’t stopped Chinese fans and critics from drawing comparisons between the two.

Chinese operas today perform mash-ups of Tang and Shakespeare. Twenty performing arts troupes from China and England gathered for a month-long commemoration of both playwrights in Fuzhou in 2017. Chinese museums have mounted exhibits comparing the Eastern and Western Bards. And Fuzhou’s government donated statues of Tang and Shakespeare standing shoulder-to-shoulder to Stratford-upon-Avon, Shakespeare’s birthplace, in 2017. The statue was unveiled on Shakespeare’s 453rd birthday.

CC BY-SA 4.0

The two bards were similarly prolific. Shakespeare has nearly 40 plays and more than 150 sonnets to his credit. In addition to his quartet of plays, Tang composed more than 2,000 poems and essays, mostly in his later years.

When The Peony Pavilion was first performed, in 1598, there were no theaters in China. So the play was staged in a garden.

In the Cultural Revolution of the mid-1960s, guards in the Red Army likely destroyed Tang’s gravesite as a symbol of China’s ancient culture and customs, even if they didn’t know that the famous playwright was entombed there. A factory was soon built over the site.

In 1980, an empty tomb was erected in Fuzhou’s People’s Park to honor his legacy.

It was the recent destruction of the 1960s-era factory and subsequent cleanup that led to the 2017 discovery of the tombs. Very little of what was originally buried was found intact, however. No bones remained. Even so, the archaeological discovery was met with celebration. The Fuzhou government plans eventually to turn the site into a tourist attraction with the epitaphs displayed. A fitting tribute to the Chinese Shakespeare.

E.L. Hamilton has written about pop culture for a variety of magazines and newspapers, including Rolling Stone, Seventeen, Cosmopolitan, the New York Post and the New York Daily News. She lives in central New Jersey, just west of New York City